Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Rashid Talukder 1939 – 2011

?Daktaaar?. The loud call would be promptly followed by a big grin and a bigger bear hug. He insisted on calling me by that title and always referred to it, when addressing me in public. Rashid Talukder (Rashid Bhai ? elder brother – to all of us) didn?t speak ?posh? Bangla, struggled somewhat with English and wasn?t encumbered with any of the polish of ?bhodrolok? upbringing many of us were trapped in. Unlike many others however, he took pride in his upbringing. That his apprenticeship involved making tea for the darkroom team, was something he was completely at ease with. There lay his charm. Quick witted, fast on his feet, streetwise, gregarious, loud and completely disarming. Rashid Talukder was an unlikely rebel who was impossible to dislike. He took ownership of my title. Despite his genius, he was all too aware of how photojournalists were regarded. In a profession way down in the pecking order of the hierarchical newsroom, he had felt the full brunt of the class structure where the photojournalist was the illiterate worker. Visually illiterate news editors would call the shots when it came to picture use. The concept of a picture editor had never entered newspaper parlance. The status my Daktar title implied to a photojournalist was something we were all going to share.

Those were the days one would check the chemistry in the developer from its taste. An extra puff of the cigarette would serve as a safelight to check if the film had been sufficiently exposed. Deadlines often meant printing directly from wet negatives. Once the twin lens reflex cameras gave way to the more versatile 35 mm, the film stock itself was often the back end of a roll of cine film bought cheaply from movie industry rejects. Fibre base wasn?t a fashionable thing in those days. It was the only type available. Chinese Xiamen and Era paper were found in limited grades with changes in the chemistry providing variation in contrast. It was in those grueling unventilated toilets converted to darkrooms that Rashid Bhai made print after print that documented the painful, rebellious, joyous moments of a young nation in the making.

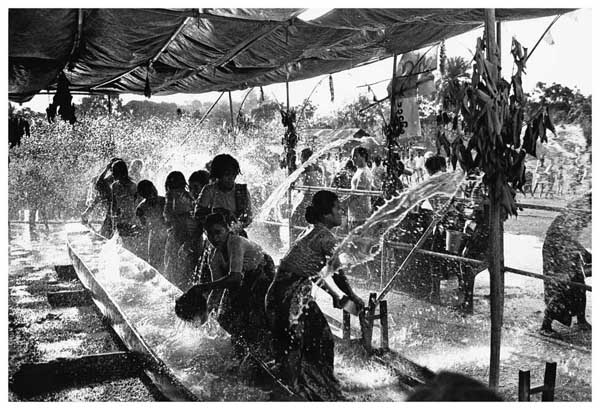

I chided him for the fact that he had never made any contact sheets. His life?s possession, a garbage bag filled with negatives in no specific order or category, made it impossible to work from his archives. But what photographs! This was the man who had witnessed every major event in Bangladesh?s turbulent history. Interspersed between the iconic images of our nation?s past were the curious observations of a natural story teller. Kids bathing in the river with a real live elephant for a rubber duck. The courtship rites of hill people, a child being blessed by a sadhu, a duck sedately walking her ducklings across a busy Motijheel street were the slices of life that peered out of the more remembered seminal moments of our history that this remarkable photojournalist had meticulously recorded.

Like the other photojournalists of his time, he too had been exploited by many. Fellow photographers who had borrowed negatives which were never returned, only to be published later in the borrower?s names. Publishers who sweet-talked him into handing over negatives and prints for which he was often neither paid nor credited. Politicians who had used his photographs to further their campaigns. Surprisingly, there was no cynicism in Rashid Bhai?s description of these events. He said them in his matter of fact way. Even the time when he had faced the brutality of a policeman, whose life he had saved in an earlier skirmish, left no trace of anger or a search for revenge. I knew full well, Rashid Bhai would yet again put his own life on the line to save the same policeman had the situation recurred. On that particular occasion, the police were still after him, and we had smuggled him out of the hospital bed, knowing he wasn?t safe there.

This was a man who knew everyone worth knowing in this land of ours. But it was his relationship with lesser mortals that characterized the man. Walking with him to a major bank was an eye opener. Sure he could walk into the office of the chairman without an appointment, but he also knew every guard, every cleaner in the building. Would stop to ask someone how his new grandchild was doing. Whether his arthritis was better. Quietly slip someone some money because he knew there was no food at home. He remained his unassuming self regardless of who was at the other end. His was a large family whose members transcended all barriers of race and class. He was everone?s Rashid Bhai.

His first editor, A B M Musa had given him a simple instruction on his first assignment. ?Arrive 30 minutes before the event, leave 30 minutes after it is all over.? Rashid Bhai had taken the message to heart, not only in terms of time, but in the spirit of the advice. He would always go that extra mile. His were the images that the others had failed to notice. The otherwise insignificant moments made significant through his discerning eyes.

In the days of territorial battles when photojournalists were barred from becoming members of the Bangladesh Photographic Society (BPS, a camera club that was more inclusive and embraced amateurs and art photographers), Rashid Bhai gave up his membership of the photojournalist association that he himself had founded, to show his solidarity with the wider fraternity. He wore the predictable ostracization as a badge of honour.

As an understudy during a trip to a photo conference in Kolkata, Rashid Bhai, then the president of BPS led our motley gang to what in those days was a major regional event. This was when I saw first hand his remarkable people skills. Hardened customs officers at the Benapole border, who knew no language other than the one of Taka, soon became long lost friends. Perfect strangers were soon inviting us home for dinner. Rashid Bhai, playing the fake prima donna, insisting on his favourite dish being on the menu. His infectious charm brought out the cheekier side of Saeeda Khanam, the veteran woman photographer, who displayed a side we had never suspected.

We had both been given an honourary fellowship by the Bangladesh Photographic Society. In the group exhibition at Shilpakala Academy (The academy of fine and performing arts), Rashid Bhai presented a set of prints all laminated with a prominent ?Gold Medallist? stamp in the corner. It had upset me at that time. They detracted from the images and I saw no reason for him to mention he was a ?Gold Medallist?. It seemed cheap. It was much later that I was able to step down from my high horse and recognize the reason for his actions. The man who had dedicated his entire life to telling the untold stories of his nation, had never been appreciated by his own public. Sure they praised him, and patted him on the back condescendingly on appropriate occasions, but he had never been given the professional respect that he deserved. The Ekushey Padak, the award given in memory of the language martyrs had never been given to the man who had done the most to enshrine that memory. Even upon Rashid Bhai?s death, the newspapers that wanted to publish his pictures, wanted them for free. ?We?ll provide a credit line? they?d say, knowing the family still had outstanding medical bills to pay. They did not respect his work, understand his craft, recognize his sacrifice. They did understand gold medals. Yes, he had stooped to their standards. Pampered to their value systems. He was prepared to do so for his profession. The ?daktar? title suddenly made a whole lot of sense.

The Lifetime Achievement Award he had been given at Chobi Mela V provided scholarships for deserving students from Bangladeshi villages to study at Pathshala, The South Asian Media Academy. My earlier attempts to get him recognized had failed. The Side Gallery had offered a grant to host his exhibition. Rashid Bhai had failed to get his work together in time. I was delighted when my nomination for the first National Geographic Pioneer Photography Award went to Rashid Bhai. Now that the award is said to be closing down, perhaps he will remain the only recipient of the prestigious award. Sadly here too the money never made it to him in time. Before he left for the United States, we arranged a long interview. Stories poured out that left us all in awe.

Rashid Bhai had felt slighted at the wedding of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman?s son. The father of the nation, sensing Rashid Bhai?s obhiman, also refused to eat at his own son?s wedding. Pride was restored and the wedding went ahead only when the two men sat down to dine together. Stories of having kathal and muri at the open house of the great Maulana Abdhul Hamid Khan Bhashani were amongst the nuggets that he shared with us that day.

That was the last day we spoke. When I visited him in hospital near Drik, he was asleep. That was the only time he had failed to hug me or call out ?Daktaar?. Adieu my friend. May they recognize your greatness in afterlife. May we learn from your loss. May the light be with you.

Shahidul Alam

Mexico City

25th October 2011

Rashid

Talukder was a founder board member of Pathshala, South Asian Media Academy and a contributing photographer to majorityworld.com. His entire work is archived at Drik Picture Agency.

2 thoughts on “The light we failed to see”