![]()

Three bombs had gone off the day before, and they weren’t comfortable about me walking on my own in the streets of Kabul.

The driver insisted that he gave me a lift. The suggestion that a particular hill not too far away would give me a good view of the city was a good one, and the late evening light was just leaking through the haze. He offered to stay to give me a lift back, but I wanted to be on my own, and writing down that I needed to get back to Choroi Malek Asghar, I wandered off, free at last. Coming down the hill, I wandered through the back streets as I tend to do in cities I am new to. An odd conversation in my broken Urdu helped. As always kids wanted to be photographed, and wherever I went, people offered me cups of tea, or invited me home.

Abdul Karim latched on to me. Insisting that I visit his family, he took me through the narrow winding mud path that led to the tiny doorway that was the entrance to his home. My first task was to take photographs of the family. I had none of the language skills he had, but it didn’t seem to matter. Initially surprised by this stranger the man had brought home, the family quickly turned to more important things, like being hospitable to this mehman (guest).

I gesticulated wildly enough to convince them that I needed to catch the light while it was there, and Abdul Karim became my self appointed guide. I could go and take some photographs, but was to come back and have tea. The sun had almost set by the time we were back up the hill. A lone runner ran circles around the flattened top of the hillock. Football fever had set in and the shouting of the kids chasing a ball in the dried up swimming pool in the centre, carried through the evening sky. Four young men came up and made conversation. Two of them had been to Pakistan, and we spoke in Urdu and in English. One was an out of work webmaster, and wanted my email address. They posed, I photographed, and he scribbled his email address so I could email the picture back.

The sun had set and Abdul Karim wanted me to keep my end of the bargain. The young men also wanted me to visit their homes. Perhaps they could take me out the following day they suggested. They knew great places for photography. We exchanged mobile phone numbers. Undiplomatically, I suggested that perhaps they too could come to Abdul Karim?s and then I could go with them to their homes. One young man took me aside and explained that they couldn’t go. It would be breaking purdah. I wondered how I had become an exception to the rule.

Abdul Karim, his mother, Bibi Shirin, his wife Ayesha, and their two children Mehjebeen and Sufia lived in this one room flat. There were mattresses on the floor and one television set and one radio. There was a tiny courtyard and metal steps that went up to what looked like a loft. Abdul Karim had worked as an engineer in the marines and was now out of a job. He showed me the children’s book he used, to try and teach himself English. Even with body language and the best of intentions, our communication faltered, but there was no mistaking that I was a welcome guest, and my major challenge that evening was leaving without having dinner with the family. The path outside was by now pitch black, and Abdul Karim walked me through the maze and got me to a cab. We parted with some sadness.

Back at the Aina office where I was staying, the guard with the Kalashnikov welcomed me with a smile. I could see why my colleague Nazrul hadn’t left the compound for the last two months.

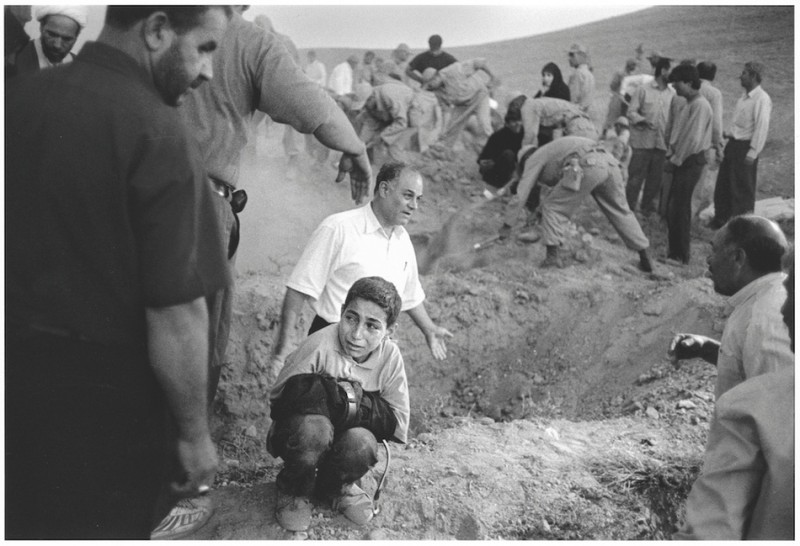

Day before yesterday we drove up to Salang, past the bombed out ruins of what had been thriving villages, past the tank carcasses, past vast stretches of barren land, interspersed with lush foliage by the river beds. A young man took great pleasure in racing his steed against our minivan. Two boys flagged me down, insisting that their friendship be recorded in my camera.

Back in Kabul, I did walk out on my own, without an escort, and went to the marketplace. The men in the bakery insisted that I try their freshly baked bread and I briefly sat with new found friends and watched Hindi films in the restaurants.

I spoke to Arif who ran a small studio, and came across the out of work labourers in the market square looking for work. A child and an old man reached into the gutter to pick up a polythene bag they could sell. It was in a worker’s face that I realized why people who are capable of so much hospitality, and are so willing to give, have become objects of terror to the foreigners who live here.

They want the very things that the west has officially championed. Jobs, security, a home for their families and for their land to be free of occupation.

Organisers at the Sarina Hotel claimed it was the first fashion show in 20 years in Afghanistan. There were few tell tale signs of the riots that had taken place here a few days ago. But the white Land Rovers outside, four sets of security barriers, and the armed US soldiers on guard, marked the distance between central Kabul and the rest of the country.

I remember Tolstoy’s words “I sit on a man’s back, choking him, and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am very sorry for him and wish to ease his lot by any means possible, except getting off his back.” They seem to have learned little in 120 years.

Choroi Malek Asghar

Kabul

9th July 2006