By Rahnuma Ahmed

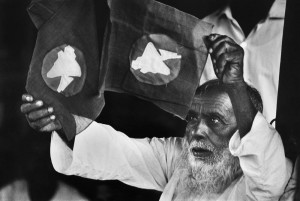

A national convention of freedom fighters organised by supporters and activists of Jamaat-e-Islami and its students? wing Islami Chhatra Shibir. An outright appropriation. The only problem is, Mohammad Ali saw through it. A single glance told him the truth. And, as Jamaat?s pack of cards came crashing down, the reaction was instant. It was violent. This, for me, was the second moment of truth. It testifies to Jamaat?s unchanged character, violence, an inability to engage with history, and to confront truth,

writes

Be what you would seem to be ? or, if you?d like it put more simply ? Never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others that what you were or might have been was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise.

The Duchess, in Lewis Carroll, Alice?s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865

IT WAS to be a convention of freedom fighters, his neighbour had told him. They had both fought against the genocidal onslaught unleashed by the Pakistan army in 1971.

On Friday, a weekly holiday morning, veteran freedom fighter Sheikh Mohammad Ali Aman had gone to the Diploma Engineers Institute in Dhaka. He had peeked into the auditorium. He had expected to see familiar faces, to hear cherished stories of loss and courage. Of a victory achieved, of justice denied. Of betrayals. Of trying the collaborators ? the local accomplices of Pakistan army?s genocidal campaign ? to right the wrongs, at least some. There were collaborators thought to be guilty of committing war crimes, but they had gone scot-free. Their political rehabilitation and brazenness in the last three and a half decades was like a wound that festers. Yet another brazen act, yet another shameless lie brings the pus to the surface. It keeps oozing out. Again, and again.

He was puzzled at the faces that he saw. None of the Sector Commanders were present. No familiar faces, faces that symbolise for him the spirit of the struggle, the spirit of the nine-month long people?s war. Mohammad Ali is a man of modest means, he earns a living by painting houses and buildings in Badda, Dhaka. Unable to recognise any of the imposing figures present inside the auditorium ? ex-chief justice Syed JR Mudassir Hossain who was chief guest, energy adviser to the previous government Mahmudur Rahman, ex-director general of the Bangladesh Rifles Major General (retd) Fazlur Rahman, Wing Commander (retd) Hamidullah Khan, ex-director general of the Bangladesh Press Institute Rezwan Siddiqui, who was the special guest, New Nation editor Mostofa Kamal Mojumdar, general secretary of the Federal Union of Journalists Ruhul Amin Gazi, journalist Amanullah Kabir ? he felt alarmed. And left. One can hardly blame him.

`So I went and sat on the lawn,? Mohammad Ali said in an interview given later. ?I saw some people come out, I heard them say, we don?t want to be part of a meeting that demands the trial of Sector Commanders. An ETV reporter came up to me and asked, are you a freedom fighter? Yes, I replied. I belonged to Sector 11, First Bengal Regiment, D Company, led by Colonel Taher. What about the trial of war criminals, what do you think? I said, I think that those who had opposed the birth of the nation, those who had committed rape, razed localities to the ground, murdered intellectuals, they are war criminals. They should be tried. Those who were chairman and members of the Peace Committees, they belong to Jamaat, and to the present Progressive Democratic Party. They should be tried, they should be hung. I think this is something that can be done only by the present government, a non-party government? (Samakal, July 13).

?Who cares for you?? said Alice (she had grown to her full size by this time). ?You?re nothing but a pack of cards!?

At this the whole pack rose up into the air, and came flying down upon her…

They swooped down on Mohammad Ali. He was kicked and locked in a room for three hours. Before his release, his voter ID card was photocopied. ?I do not wish to say what they did to me. It will bring dishonour to the freedom fighters,? was all he said of his ordeal. ETV reporter Sajed Romel, also made captive, was released an hour later, after his colleagues rushed to his rescue. The camera crew, fortunately, had escaped earlier, with its recorded film intact.

Engineer Abdur Rob, a vice-president of Jatiya Muktijoddha Parishad ? the organisers of this farce ? was asked why a veteran freedom fighter and an electronic media journalist had been locked up. He replied, ?Impossible. Such a thing could not have happened.? Prothom Alo?s reporter was persistent, it was filmed. We have it. ?Well then,? came the immediate reply, ?it was an act of sabotage. Our people could never have done such a thing.?

New lies. Emergency lies

Soon enough, press releases were handed out by Jatiya Muktijoddha Parishad detailing the sabotage story: Prothom Alo, Samakal, Jugantor, Inquilab, and Daily Star were guilty of spreading lies. Some persons had come to the national convention without any delegate cards, they had tried to barge in, JMP volunteers had wanted to see their invitation cards, their responses had been unsatisfactory. Instead of covering the main event, the ETV news crew had shot something else, it was staged by hired people and instigated by yellow journalists. These acts, deliberate and pre-planned, were aimed at wrecking the convention. They had failed. Jatiya Muktijoddha Parishad is an authentic organisation of freedom fighters. It is not affiliated to any political party. The liberation struggle is above party affiliation. Journalists are demeaning the honour of freedom fighters by propagating lies. They are creating disunity.

A later press release added more details: no one by the name of Mohammad Ali had been invited to the national convention of Freedom Fighters. The ETV?s interest in interviewing him proves that it was staged, it was a conspiracy aimed at foiling the convention. Politicians are attempting to capitalise on the incident. The JMP calls on all freedom fighters to stay united (Naya Diganta, 13, 15 July).

Newspaper reports, however, provide concrete details. Jatiya Muktijoddha Parishad was formed on January 26 this year. After the Sector Commanders Forum had demanded the trial of war criminals. The JMP?s office is located in a room rented out by an organisation headed by ATM Sirajul Huq, ex-amir, Paltan thana, Jamaat. It is not registered with the liberation war ministry. This, according to legal experts, makes it illegal. Three high-ranking members of the Parishad claim that they had fought in 1971. These claims are false. Muktijoddha commanders of the respective areas do not know them. Executive committee members of the Parishad include men who contested parliamentary elections on behalf of Jamaat-e-Islami. Vice-president Engineer Abdur Rob had admitted to journalists, yes, the Parishad did receive ?donations? from Jamaat-e-Islami.

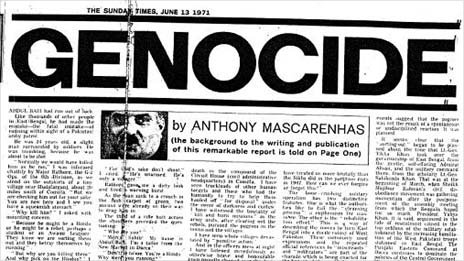

The story about Jamaat?s role in the liberation struggle, the liberation struggle itself, whether it was genocidal or not, whether war crimes should be tried or not, who was on which side, is an evolving one. What interests me particularly is how Emergency rule, and its raison d?etre of removing corruption and corrupt political practices for good, has impacted on Jamaat?s story. On its warped sense of history. Last October, as Jamaat?s secretary general Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mujahid was leaving the Election Commission after talks on electoral reforms, he was asked about the growing demand for declaring anti-liberation forces, and war criminals, disqualified from contesting in the national elections. He had replied, the charges against Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh are ?false?, and ?ill-motivated?. There are no war criminals in the country. He had added, ?In fact, anti-liberation forces never even existed.? A day later, in an ETV talk show (26.10.2007) Jamaat-sympathiser and former Islami Bank chairman Shah Abdul Hannan had said, there was no genocide in 1971. Only a civil war.

And now this. A national convention of freedom fighters organised by supporters and activists of Jamaat-e-Islami and its students? wing Islami Chhatra Shibir. An outright appropriation.

The only problem is, Mohammad Ali saw through it. A single glance told him the truth. And, as Jamaat?s pack of cards came crashing down, the reaction was instant. It was violent. This, for me, was the second moment of truth. It testifies to Jamaat?s unchanged character, violence, an inability to engage with history, and to confront truth.

Old truths

Historical research which includes newspaper reports, speeches and statements made by those accused of war crimes, attests to the fact that Mujahid, as president of East Pakistan Islami Chhatra Sangha, and as chief of the Al-Badr Bahini, collaborated with the Pakistan army in conducting massacres, looting and rape. Also, that he had led the killings of renowned academics, writers and poets, doctors, engineers, and journalists, which occurred two days before victory was declared on December 16. Senior Jamaat leaders Abdus Sobhan, Maulana Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, Abdul Kader Molla and Muhammad Kamaruzzaman, who accompanied Jamaat?s secretary general to the Election Commission for talks on electoral reforms last October, are also alleged to have committed war crimes. According to the People?s Enquiry Commission formed in 1993, Jamaat?s amir Matiur Rahman Nizami, as commander-in-chief of Al-Badr, is also guilty of having committed war crimes.

Who needs Jamaat?

Both the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party had accepted Jamaat as an ally during the anti-Ershad movement. After the national elections of 1990, Jamaat support had ensured the BNP its majority in the fifth parliament. The Awami League, which claims to have led the liberation struggle, joined forces with Jamaat to help oppose and oust the sixth parliament. In the seventh parliament, the Awami League inducted at least one identified war collaborator in the cabinet. And, in the eighth parliament, the BNP paid the ultimate tribute by forming government with Jamaat as a coalition partner.

But what about now? That this government, the Fakhruddin-led, military-controlled government, is giving Jamaat-e-Islami a kid gloves treatment has not escaped unnoticed. Jamaat?s amir Matiur Rahman Nizami was one of the last top-ranking leaders to be arrested. He was also one of the earliest to be released, that too, on bail. Hundreds, possibly thousands, of party supporters were allowed to gather on the road to cheer his release last week, while the banner of Amra Muktijuddher Shontan activists, who had formed a human chain the next day, to protest against the assault on Muhammad Ali, was seized by the police. The Bangla blogging platform Sachalayatan could no longer be accessed after a strongly worded article on the assault of Muhammad Ali was posted. Was it a coincidence? Or, are the two incidents related? When asked, ABM Habibur Rahman, head of BTCAL internet division, refused to comment. One of the founders, who lives in Malaysia, has confirmed that the blog can be accessed from all other parts of the world.

As the US expands its war on terror, its venomous civilisational crusade of establishing democracies in the Middle East, one notices how Bangladesh has gradually been re-fashioned as a ?moderately? Muslim country, in an area considered to be ?vital to US interests?. Jamaat-e-Islami, in the words of Richard Boucher, US assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asian affairs, is a ?democratic party?. James F Moriarty, US ambassador to Bangladesh, in his congressional testimony (February 6, 2008), said US interest in Bangladesh revolved around the latter denying space to ?terrorism? (mind you, Islamic, not US, not state-sponsored).

Moriarty?s ideas echo Maulana Matiur Rahman Nizami?s. In an interview given last year, Nizami said, Jamaat was important to keep Bangladesh free of militancy and terrorism (Probe, June 27-July 3, 2007). Interesting words coming from a person who had, three years earlier, as amir of the then ruling coalition partner and industries minister, denied the existence of militancy in Bangladesh. Bangla Bhai was the ?creation of newspapers?, it was ?Awami League propaganda?.

The US and Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh fashioning a new partnership on war on terror? chorer shakkhi matal, many Bengalis would say. The drunkard provides testimony for the thief.

———–

First published in The New Age on Monday 21st July 2008