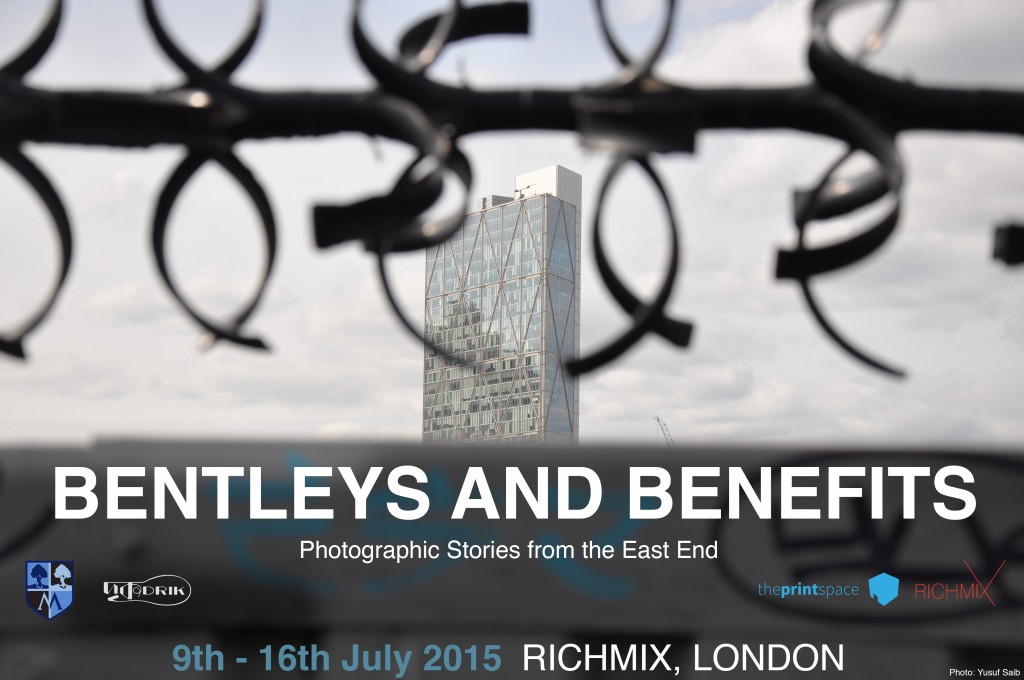

Bentleys and Benefits is a unique exhibition at?Rich Mix?capturing the story and social diversity of the East End through the eyes of the young people who live here. The exhibition brings together the outcomes of ?Demystifying Photography?, a series of photography workshops, by?Drik Picture Library, Dhaka in collaboration with?Rich Mix?and?Morpeth School.

Five workshops between October 2014 and June 2015 were conceived to offer the youth of East London an opportunity to work with?Shahidul Alam, founder of?Drik?and world-renowned photographer, writer and activist from Bangladesh, and learn how to use digital technology to capture a memorable image by using key elements of story telling. By exploring emotion and perspective, and studying qualitative shifts between first person and third person narratives,?Alam?introduces the often-neglected sphere of visual literacy.

The photographers, all sixth form students at?Morpeth school, have been working closely with?Alam, to develop their own voice through photography; resulting in an intimate, compassionate and inclusive dialogue shaped by their experiences of life in Bethnal Green. The result is a photographic journey through the financial and social landscape of this extraordinary area of London.

Photographers: Arshad Ali, Fahim Ali, Halima Khanom, Mohammad Nahid Zakaria, Mohammad Zackariyya Ullah, Zayn Ali, Yusuf Saib?(Morpeth school)

Workshop Leader:?Shahidul Alam?(Drik)

Text: Mohammad Zackariyya Ullah (Morpeth school), Mary George (Drik)

Flyer Design: Yusuf Saib?(Morpeth school)

Logo Design: Yusuf Saib?(Morpeth school)

Social Media: Halima Khanom, Mohammad Zackariyya Ullah, Arshad Ali?(Morpeth school)

Fundraising: Zayn Ali, Mohammad Nahid Zakaria (Morpeth school), Mary George (Drik)

Coordinators: Matthew Keil and Sam French (Morpeth school), Mary George (Drik)

Project Management: Saiful Islam (Drik)

Prints proudly supported by?theprintspace.

![]()

Tag: visual literacy

Are too many people taking photographs?

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

By Pedro Meyer

Zonezero.com

I have been asked many times what I think about the fact that nowadays almost everyone takes pictures. The question of course, has a sort of hidden agenda. It suggest that photography has become so common place so as to render photography into a commodity, taking away from it, it’s aura of sophistication, uniqueness and or the merit of being seen as some form of art, after all most people make pictures that are quite bad.

All along my answer has been consistently the same. I more than welcome the fact that so many more people today take pictures in comparison to, lets say, just ten years ago. Let me explain: if we were having this debate over the written word, probably no one would object that a nation make all the needed efforts to achieve total literacy. As a matter of fact, all over the world there is a strong awareness of how important it is for its population to become literate, at least in the dominant language of the country in question.

No one in their right mind, would expect someone to jump from not being able to read and write to becoming a laureate poet. Yet somehow the expectations that are being upheld for photography are a bit like that. We expect photos taken by people who yesterday did not even have a camera, to come up with at least good images, and if it does not happen then we should somehow be disappointed.

Let us look at this more in detail. To be visually illiterate is the equivalent to not knowing how read and write. However, as cameras have become more ubiquitous, and the price of the instrument coming down considerably, and the cost of taking a picture near zero , the number of pictures taken have increased exponentially. In other words, more and more visually illiterate people are making pictures because they can, not because they acquired a great visual culture before making their pictures.

Add to that, the fact that all the new technologies we have available today, have created cameras that are so intelligent that they make most of the decisions for the photographer with regard to the exposure and sometimes even the framing, allowing our new found photographer to obtain results that reward the efforts of pressing the shutter button. It’s almost the equivalent of someone speaking to a microphone and the computer translating the sound of the voice, into a written text. We would not say that this person had in fact learned how to write. Well much the same happens when a camera takes a picture that is acceptable even though the person behind the lens has no knowledge of photography what so ever.

So we have that the entry cost has come down so much that it has made the picture making process a lot more democratic. Add to that, the technology has empowered everyone to have some kind of satisfactory result. This would suggest that although pictures are being made, they apparently are not the outcome of a deliberate decision making process as when you really know what you are doing. After all security cameras register images and we would not call such results as being provided by a photographer.

Having said this, we have to wonder how accurate such thoughts really are. After all how can one say that someone does not know at all what they are doing. Maybe what is happening today has to be viewed in a completely different light ( no pun intended). Consider how any teenager sending pictures to all his or her friends, with regard to their latest adventures, would certainly fall into the realm of autobiographical expression, even though such a category might be far removed from any conscious decision making process. In fact I would think that this tidal wave of images, has left the intellectual community confronted with new challenges to understand and see photography in a “new light”. Certainly the concept of “bad photography” is taking hold as a new concept that has to be dealt with. Has “bad photography” liberated “good photography” from becoming something else?

As I see it, with so many millions of people, the world over, having now explored making images, their curiosity for doing something different and new to their previous results will probably lead many to a new era of acquiring more and more visual literacy and technological know how, and leave the curatorial world scratching their heads as to what to make of it all. How could anyone dealing with photography in the XXI century, dismiss as trivial the shear volume of photographs that have been created. The collective document that has been produced world wide, documenting so much of our daily life in this period, will surely become a fundamental piece of information for generations to come. If this was it’s sole merit, that alone would already give importance to all that has been photographed.

This opens up the field of photography in the realm of education and publishing in ways that will probably explode in the years to come.

The entry cost to participate in the creative world has come down so much that we can truly say that if you want to make a film, record a disc, make photographs, publish a book, and so on, it’s not something that is beyond your means, as it was not too long ago. It has finally come down to the most meaningful part of the act of creating, and that is that you have something meaningful to share. And if you don’t know what to say then don’t worry, then at least have a lot of fun doing what ever strikes your fancy, that also counts as contributing in some degree to the well being of all those around you, after all happiness is contagious, and who knows, maybe without you knowing it, are changing the face of photography for ever.

I am personally very gratified to see so many people in the world engaged in creative activities that we could hardly believe possible not too long ago.

Pedro Meyer

Coyoac?n, Mexico City

November 2010

First published in zonezero.com

I hear the screams

![]()

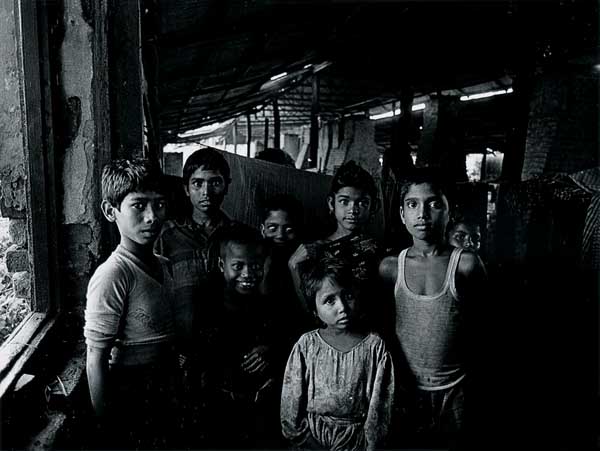

Even after years of playing Pied Piper with a camera, I am still taken aback by children insisting on being photographed. It was September 1988, and we had had the worst floods in a century. These people at Gaforgaon hadn’t eaten for three days. A torn saree strung across the beams of an abandoned warehouse created the only semblance of a shelter. Their homes had been washed away. Family members had died. Yet the children had surrounded me. They wanted a picture.

It was dark in that damp deserted warehouse, but the broken walls let in wonderful monsoon light, and they jostled for position near the opening. It was as I was pressing the shutter that I realised that the boy in the middle was blind. He had pushed himself into the centre, and though he wasn’t tall he stood straight with a beaming smile.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CARE

Clip on story of the blind child, from keynote presentation on citizen journalism at 50th Anniversary of World Press Photo in Amsterdam.

I’ve never seen the boy again, and today I question the fact that I do not know his name. But he has never left my thoughts and often I have wondered why it was so important for that blind boy to be photographed.

It’s happened elsewhere, in boat crossings at the river bank. In paddy fields heavy with grain, in busy market places. A shangbadik (literally a journalist, but in practice any person with a half decent camera) was hugely in demand. They refused to take the fare from me at the ferry ghat. Opened up their hearts and told me their most personal stories. Confided their secrets, shared their hopes. Never having deserved such treatment it has taken a while for me the photographer, to work out why being photographed meant so much to that blind child.

The stakeholders of Bangladeshi newspapers are the urban elite. Consequently stories from the village are about the exotic and the grotesque. Village people exist only as numbers, generally when plagued by some disaster and only when figures are substantial. A photograph in a newspaper, regardless of how token the gesture, is the only time a villager exists as a person. A picture on a printed page would have lifted that blind boy from his anonymity. That humbling thought stays with me whenever I am feted as a shangbadik in some small village. I receive their gift of trust gently, careful not to break the delicate contents.

It was as a photographer of children that I had begun my career. It was way before 9/11 and one could make appointments with strangers and go to their homes. I took happy pictures of kids, and parents loved them. It was easy money, except when I would photograph the children of poor parents. They loved the pictures but couldn’t afford to pay, so I would quietly leave the pictures behind and pay the studio out of my pocket. Back in Bangladesh, the only way I could make money was as a corporate photographer, but something else was happening. We were in the streets, trying to bring down a general who had usurped power. I didn’t know it then, but I was becoming a documentary photographer. Suddenly taking pictures of children meant more than smiling kids on sheepskin rugs.

As the pressure against the general mounted, I photographed children who joined the processions. The night he stepped down, I photographed a little girl with a bouquet of flowers. She was out with her dad in the middle of the night, celebrating the advent of democracy.

I am back in Kashmir eight months after I had been here photographing the advent of winter. The valleys of this fertile land are green with new crops,

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

but many of the homes are still to be rebuilt. As I walked through the rubble, the kids again wanted to be photographed.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Najma came running, her bright red dress popping out of the green maize fields.Unsure at first, she smiled when I told her she had the same name as my sister.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Zaheera, a cute girl with freckles, gathered her friends and sang me nursery songs. But my thoughts are far away. Despite the laughter and the nursery songs very different sounds enter my consciousness. I remember the children screaming on the night of the 25th March 1971, when I watched in helpless anger as the Pakistani soldiers shot the children trying to escape their flame throwers. The US had sent their seventh fleet to the Bay of Bengal, in support of the genocide. Today, as I remember the Palestinians and the Lebanese that the world is knowingly ignoring, I can hear the bombs raining down on Halba, El Hermel, Tripoli, Baalbeck, Batroun, Jbeil, Jounieh, Zahelh, Beirut, Rachaiya, Saida, Hasbaiya, Nabatiyeh, Marjaayoun,Tyr, Jbeil, Bint Chiyah, Ghaziyeh and Ansar and I hear the screams of the children. Piercing, wailing, angry, helpless, frightened screams.

News filters through of the children killed in the latest bombing. The photographs have kept coming in, horrific, sad, and disturbing. Mutilated bodies, dismembered children, people charred to ashes. But none as vulgar as those of Israeli children signing the rockets. Death warrants for children they’ve never known.

I remember my blind boy in Gaforgaon. The Lebanese and the Palestenians are also people without names. Their pain does not count. Their misery irrelevant, their anger ignored. Sitting in far away lands, immersed in rhetoric of their choosing, conjuring phantom fears necessary to keep them in power, hypocritical superpowers fail to acknowledge the evil of occupation. The ‘measured response’ to a people’s struggle for freedom will never in their reckoning allow a Lebanese or a Palestinian to be a person.

When greed becomes the only determining factor in world politics. When the demand for power, and oil and land overshadows the need for other people’s survival, I wonder if those screams can be heard. I wonder if those Israeli children will grow up remembering their siblings they condemned. I wonder if through all those screams the war mongers will still be asking “why do they hate us”?

11th August

Siran Valley, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan