Remarkable: Noam Chomsky

Absolutely stunning: Jess Worth. New Internationalist Magazine (Oxford)

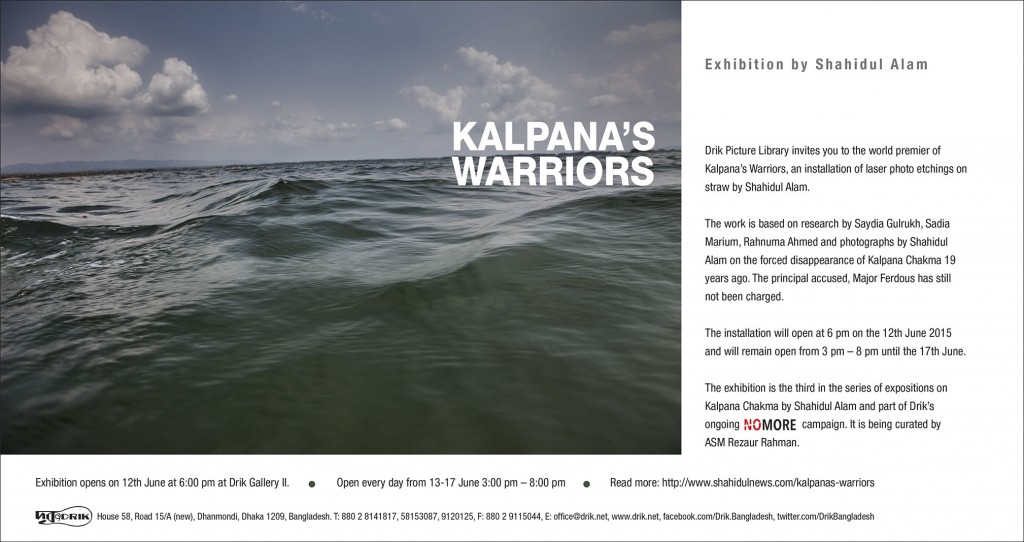

They told me you were quiet. But I felt the rage in your silence. That when you spoke, they rose above themselves. But I felt their fear. That they held you amidst them. But I felt their loneliness. They pointed to the Koroi tree where you would all meet. The banyan tree under which you spoke. Ever so powerfully. They pointed to the mud floor, where you slept. I touched the mat that you had rested upon, and I knew I had found the vessel that must hold your image.

They had tried to erase you, your people, your memory. They had torched your homes and when coercion failed, when you remained defiant, they took you away, in the dead of night.

The leaves burned as the soldiers stood and watched. The same leaves they weave to make your mat. The same leaves I shall burn, to etch your image. Will the burning mat hold your pain? Will the charred leaves hold your anger? Will the image rising from the crisp ashen leaves reignite us? Will you return Kalpana?

For nineteen years I have waited, my unseen sister. For nineteen years they have waited, your warriors. Pahari, Bangali, men, women, young old. Was it what you said? What you stood for? Was it because you could see beyond the land, and language, the shape of one?s eyes and see what it meant to be a citizen of a free nation? For pahari, bangali, bihari, man, woman, hijra, rich, poor, destitute, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Buddhist, Atheist, Agnostic, Animist.

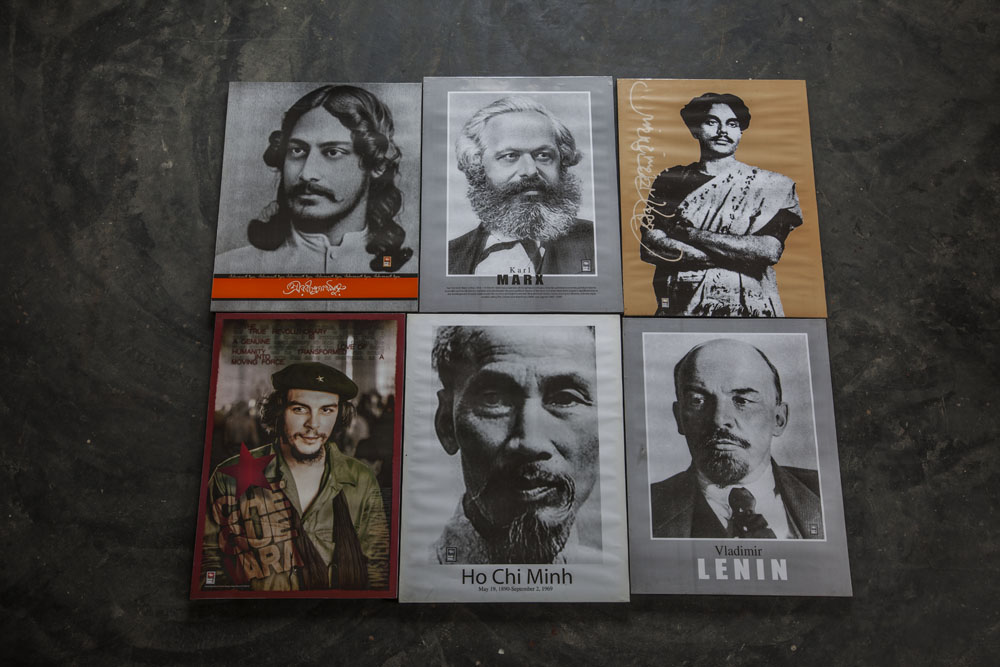

You had reminded us that a nation that fought oppression, could not rule by oppressing. That a people that fought for a language, could not triumph by suppressing another?s. That the martyrs who died, so we might be free, did not shed their blood, so we could become tyrants. That we who overcame the bullets and bayonets of soldiers, must never again be ruled through the barrel of a gun.

That Kalpana is what binds us. That is why Kalpana, you are not a pahari, or a woman or a chakma or a buddhist, but each one of us. For there can be no freedom that is built on the pain of the other. No friendship that relies on fear. No peace at the muzzle of a gun.

These Kalpana are your warriors. They have engaged in different ways, at different levels, sometimes with different beliefs. Some have stayed with you from the beginning. Others have drifted. They have not always shared political beliefs. But for you Kalpana, my unseen sister, they fight as one.

The Process

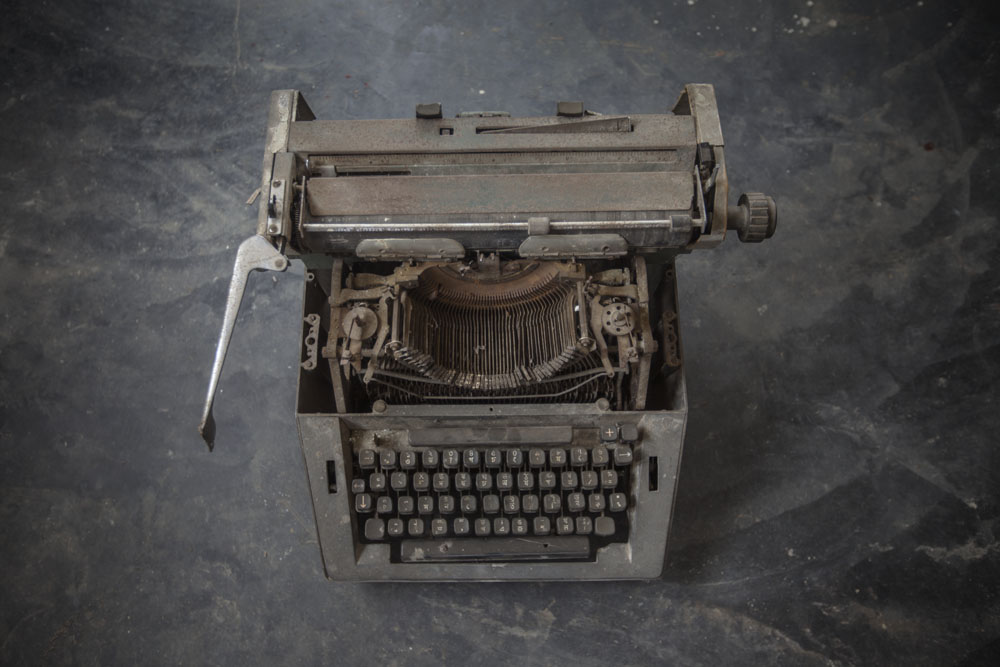

The process involved in creating these images are rooted to the everyday realities of the hill people, the paharis. Repeatedly, the interviewees talked of the bareness of Kalpana?s home. That there was no furniture, that Kalpana slept on the floor on a straw mat.

Sadia Marium making prints for my upcoming show on Kalpana Chakma #justiceforkalpana #eavig #CHT #military #bangladesh #rights #photography

A photo posted by Shahidul Alam (@shahidul001) on

Rather than print on conventional photographic media, we decided we would use material that was part of pahari daily lives. The straw mat became our canvas. The fire that had been used to raze pahari homes, also needed to be represented, so a laser beam was used to burn the straw, etching with flames, the images of rebellion.

It was the politics of this interaction that determined the physicality of the process. The laser beam consisted of a binary pulse. A binary present on our politics. In order to render the image, the image had to be converted in various ways. From RGB to Greyscale to Bitmap, from 16 bit to 8 bit to 1 bit. To keep detail in the skin tone despite the high contrast, the red channel needed to be enhanced. The Resolution and intensity and duration of the laser beam needed to be brought down to levels that resulted in the straw being selectively charred but not burnt to cinders.

A screen ruling that separated charred pixels while maintaining gradation had to be carefully selected. And then, working backwards, a lighting mechanism needed to be found that broke up the image into a discrete grid of light and dark tones, providing the contrast, the segmentation and the gradation, necessary to simulate the entire range of tones one expects in a fine print. This combination of lighting, digital rendering, printing technique and choice of medium, has led to the unique one off prints you see in this exhibition. A tribute to a unique woman that had walked among us.