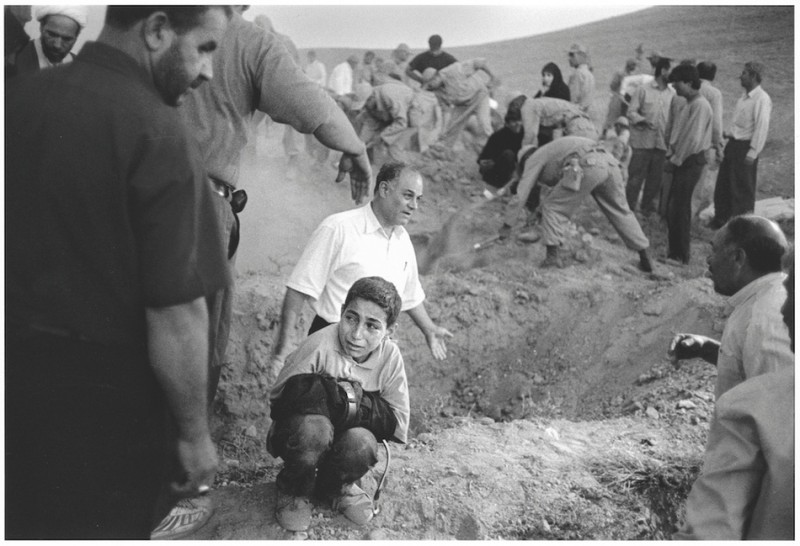

Why do I do what I do? I know how I started, partly by accident, when I got stranded with a camera I had bought for a friend, but that in itself cannot explain the joy, the passion, the amazing high that I get when I see something magical in my frame. So I’m a photojournalist. Like so many others who started off in this noble profession, I too believed I was going to change the world through my images. It took a while for reality to settle in. A while to know, that taking good pictures wasn’t enough. There were gatekeepers who decided which pictures would get used, and how they might be used, and the gatekeepers generally didn’t share my ideology or passion.

It was children who shaped my visual world. Initially, as a photographer in London, I would go round asking adults with children, if I could take portraits of their kids. Some would agree, and I would go over to their homes, put down my synthetic sheepskin rug, get the kids to smile at my camera and take happy pictures. If things went well, they would buy some pictures, and we would all be happy. Not the ultimate in photography, but it paid the bills, and helped me save some money that I thought would allow me to start afresh back home.

In Bangladesh, the children had been swapped for a new range of subjects. Ice cream and plastic toys, the odd glamour shot, some celebrity. Ceramics and fancy machines. I photographed the lot. It was as an activist, in our attempt to remove an autocratic leader, that my camera finally knew what it wanted. With the adrenaline flowing as we marched through the teargas, my camera learned to love the smell of the streets. We braved the curfew, to photograph the courage of a people and the tyranny of a tyrant. I never got a picture published in those days, as a democracy movement in the majority world, was simply not news. A flood or a cyclone was much more interesting. But when we eventually forced the dictator to step down, I photographed the rejoicing, and later at our long awaited election, I photographed a woman casting a vote. When we put up the images for an impromptu exhibition, over 400,000 people came to our three day show.

But international media wasn’t interested, and it wasn’t till the cyclone in 1991, that they started asking for images again. The same western photographers came over at the first smell of disaster, and went back with the same helpless images, reducing a proud people to icons of poverty. Even locally, the images we produced and the words we wrote, seemed to have little effect. This powerful tool that I thought I’d picked up, suddenly felt blunt in the face of corruption and indifference.

That was when, while talking to a group of working class children I was training, I was shaken. Sitting on the school verandah, 10 year old Moli, looked at the photograph of the bodies of children being dragged. ?O that was the fire in number 10? she said.

“How do you know?”

“Everyone knows.”

“What happened?”

“Nothing ever happens.”

Then she waits a bit, and says, “If I had a camera, I’d take his picture and put that guy in jail.”

It was the conviction of that 10 year old girl, that fired me up again. I remembered a moment six years ago, during a flood, where children who had taken shelter in a warehouse, insisted that I take a picture of them. As they stood by the large open window, all proud and standing at attention, I noticed that the boy in the centre was blind. He stood with his chest out, pushing back the other kids. Staring straight out at the camera he couldn’t see for the photograph he would never know. I began to realise how much more important the photograph was than simply my weapon for change. It represented hope and belief and could give a sense of dignity to many.

My photography slowly changed, as did the world around me. I began to see things that had never existed before. People mattered in a way that they hadn’t mattered before. The man in our neighbourhood, who collected the garbage late at night, pushing his cart in the rain, gathering each scrap of paper that he could sell to keep his family alive, took on a stature of enormous proportions. I wanted my camera to do what Moli and that blind boy had willed it to do. I wanted my camera to befriend the man with the cart. I felt ashamed, I had never stopped to ask his name.

It was at about that time that I met Abdul Malik, on an Aeroflot plane bound for Tripoli. He dreamt of somehow changing his destiny, and I dreamt of somehow documenting his dream. I have never met Abdul Malek since, and I don’t know if came back home and bought the piece of land he hoped to buy, and whether he was able to arrange a marriage for his sister, but I have seen that dream in many eyes. When the very things that the wealthy aspire to, becomes part of a migrant’s dream, the dream becomes illegal. I want my images to challenge that illegality, and all the illegalities that are sprouting around us. The illegality of a right to a homeland, the illegality of protest against oppression. The illegality of wanting a better life. I want to photograph Moli’s dream and that of the blind boy and the man with the cart.

Shahidul Alam

17th August 2003