![]()

![]()

Pathshala, The South Asian Institute of Photography celebrates its 10th anniversary

Elita Karim

Star Weekend Magazine Volume 7 Issue 5 February 8 2008

?D. M. Shibly

?D. M. Shibly

Members of the Pathshala family have a lot to celebrate. ?My son had once written an essay in class, where he wrote that his mother is a photographer,? says Munira Morshed Munni, freelance photographer, photo editor at Drik News and teacher at Pathshala. She is also one of the first students of Pathshala, and has been with the school for the last ten years. ?His teacher, upon reading the line, immediately cut it out, assuming it to be a mistake made by the child. Later on, I had to go speak to her and explain that I really am a photographer and also make a living out of it. She was dumbstruck for a while.? You can’t blame the teacher, adds Munni. It is still very difficult for the society to accept this art-form as anything but a hobby, a side interest or a skill that is more or less limited to documenting wedding receptions or capturing nice images. Most people are unaware of the detailed calculations made by the seasoned photographer, of the possible number of angles that can be used for one shot, or the analysis of composition, frame and subject in the blink of an eye.

Left to Right ? Saikot Majumder, Sazzad Ibne Syed, Abir Abdullah

Left to Right ? Saikot Majumder, Sazzad Ibne Syed, Abir Abdullah

Pathshala, The South Asian Institute of Photography, located on Panthapath, has played a pivotal role in the last decade, in changing the social attitude towards photography as a profession. Offering basic and advanced levels courses in this field, the institution also offers diploma and Bachelor equivalent courses to students. Very soon, a Master’s level programme will also begin in collaboration with the University of Liberal Arts. The school is also a part of the upcoming regional Master’s programme between universities in Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, Nepal, Norway and Pakistan.

Back in 1998, Pathshala had begun as a part of a three-year World Press Photo educational initiative in 1998. As the name Pathshala symbolises the ancient education system held in the open air, under the shade of a tree, free from the confining walls of a classroom, the institute emphasised on not merely conventional teaching the students. It allowed students to ask questions and develop their own style and perspective. The school was designed in a way that leads students to experience knowledge beyond the confines of the discipline.

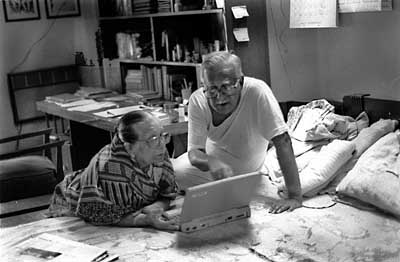

Dr. Shahidul Alam speaking on the institute’s anniversary ? D. M. Shibly

Dr. Shahidul Alam speaking on the institute’s anniversary ? D. M. Shibly

According to Shahidul Alam, the Principal of the school and MD of Drik, Pathshala strives to do much more than teach photography. ?It is about using the language of images to bring about social change. It is about nurturing minds and encouraging critical thinking. It is about responsible citizenship. In a land where textual literacy is low, it is about reaching out where words have failed. In a society where sleek advertising images construct our sense of values, studying at Pathshala is about challenging cultures of dominance.? Dr. Shahidul Alam speaking on the institute’s anniversary. According to Alam, in the South Asian region, the need for a structured education in photography has always been felt. Since photography plays a significant role in the mainstream media, this need is mostly felt in the field of photojournalism. ?The people’s right to information is generally not recognised by the official media in many countries,? he says. ?This is clearly also true for the SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation) nations. The lack of sufficient professional skills in the media, especially in the field of photojournalism, has also allowed successive governments to pass on propaganda in place of news, and the people’s role in governance has been totally ignored.? Interestingly enough, most students, who go to this school, are studying subjects like Engineering, Medicine, BBA at other universities to comply with the conventional social mindsets. There are some, however, who end up choosing between passion and tradition, hence letting go of the so-called educational system approved by society. One such student is Azizur Rahman Peu, editor of Drik News, teacher at Pathshala and also one of the first students to have entered the school ten years ago. ?I was studying medicine in Rongpur,?he says, ?when I practically ran away from home to Dhaka. I wanted to be a journalist. Back then, I didn’t know how one would define a journalist. I used to think that a photographer was, obviously, what described a journalist, capturing and documenting moments in history. My love for photography, eventually, led me to start studying here at Pathshala.? Pathshala’s certificate awarding ceremony. Blaming not only the social net, but also the media in Bangladesh, students claim that even inside newsrooms, photographers are not given their worth. A photograph tells a story as well, which should complement the journalist’s written work, rather than act as a side support. ?Newsrooms have news editors,? says Shahidul Alam. ?However, the concept of a photo editor is not seen in newspaper offices here.? According to Alam, it was the Independent in the UK which had practically revolutionised the way photographs were used in newspapers, hence breaking the system. ?Other newspapers like the Guardian had to eventually accept this idea as well.? Pathshala also has regular academic exchanges between Oslo University College in Norway and Edith Cowan University (ECU) in Australia. It is not really an exchange programme, since students from these countries come to Bangladesh to learn about photography and not the other way around, adds Alam. However, this provides Pathshala students an opportunity to share experiences with students of very different backgrounds. ?The long-term partnerships with Sunderland University, Bolton University and the Danish School of Journalism, offer educational opportunities for students with other world class institutions. The internship opportunities at Drik, Chobi Mela and Drik News offer on-the-job training that is invaluable in professional life. The regular participation in international festivals and workshops provide a world-view essential to becoming established in the global marketplace. And then there is the acid test. Emerging students are in demand, and ever since Pathshala started, all students who have graduated are gainfully employed. Some are already at the very top of their profession,? says Alam. Celebrating a decade with fireworks. Norman Leslie, the programme director from ECU, says that his students have had the chance to experience life in all its reality and colours through this exchange programme. ?ECU is located in Perth, which is a city extremely isolated even in Australian terms,? says Norman. ?Students from this university, besides having the advantages of international exposure through this programme, have also created a certain bond between the two cultures which is extremely important when it comes to the art of photography.? Even though passionate about art and photography from an early age, Shahidul Alam had decided to take up photography as a profession by accident. Back in the 80s, Alam was doing his PhD in Chemistry in the United Kingdom. As was the norm and still is in the society, studying a proper subject define the integrity and depth of being a true man. ?And that is what my parents believed as well,? says Alam. ?I did not have much money and would work to pay my tuitions.? One of his close friends got into the airlines business and asked him to fly to the United States with him. ?A poor student like me would never get this opportunity ever again and so I decided to go. My friend in the UK asked me to bring him back a camera since cameras were cheaper in the US.? Alam got a full set complete with a tripod and lens and got back to the UK, only to find that his friend did not have the money to pay him back. ?And I was stuck with it!? laughs Alam. Pathshala recently entered its tenth year. Celebrating the school’s anniversary, a three day festival was organised where both the old and the new students presented their works, amidst other festivities.

Pathshala’s certificate awarding ceremony ? D. M. Shibly

Pathshala’s certificate awarding ceremony ? D. M. Shibly

A photography exhibition titled ?Studying Life? began marked the beginning of the festival on February 1 at the Drik Gallery. Exhibiting works by some of the most celebrated students of the school, this event was inaugurated by Atiqul Huque Chowdhury and Dr. Shahidul Alam. The exhibition, which will continue up to February 15, features thirty six photographers, including Munem Wasif, Abir Abdullah, GMB Akash, Tanvir Ahmed and many more. On February 2, certificates were distributed to the students who had finished their respective courses, starting from the basic to the undergraduate level. ?We had a full-fledged festival, complete with a winter Pitha Utshob,? says Joseph Rozario, the Administrative Manager of Pathshala. ?Students, teachers, along with a few photographers from outside the country had discussions on photography. These photographers also presented some of their unique works. The day ended with a film made by one of our own students,? he says.

Celebrating a decade with fireworks ?D. M. Shibly

Celebrating a decade with fireworks ?D. M. Shibly

The last day of the festival, February 3, was an ?absolute blast,? according to Din M Shibly, a Pathshala graduate who now teaches at the school and works for the monthly magazine Ice Today. The highlight of the day was when Prachyanat, the musical theatre group, performed at the school, much to the delight of the students and also a number of guests who had turned up at the celebrations. The notion that photography cannot be a proper career no longer holds true. Many students from Pathshala are working in the media, both local and international. Tanveer Ahmed, student of Pathshala who now works at Drik News, recently had one of his photographs published in the Time magazine as the picture of the year. The photograph shows a grandfather carrying the dead body of his grandchild after being hit by the Sidr cyclone last year. Many other Pathshala students have won international awards. Alam says that young people believe that there is more glamour and less money in this profession. ?It is actually the other way around,? he explains. He plans to work more on visual literacy, hold workshops in schools and develop this field as an academic subject in the educational institutions in Bangladesh. Photography is much more than capturing a mere image. It is what one captures within the image; emotions, environment, thoughts, social perceptions and so on. One simply has to look into a photograph to discover these elements, rather than looking at it. As actor and author Sir Dirk Bogarde had put, ?The camera can photograph thought.?

Tag: school

The Last Goodbye

She would put on a burkha every morning so that choto chacha, my dad?s younger brother, could drop her off at her parents. He would take her to her college instead. That was how Quazi Anwara Monsur graduated. Dadi didn?t want her daughter-in-law to be getting an education, but Amma had the full support of Abba, my father. Her in-laws probably knew what was going on, but as long as Dadi?s authority was not directly challenged, Amma was quietly allowed to complete her studies.

Amma had made a mark upon her arrival from Kolkata to her in-laws in Faridpur. Word had gotten round that Monsur?s wife knew how to shoot a gun. She had many other skills too, and being a school teacher was also able to support the family. When Phupuabba (my father?s brother-in-law) died, the orphans were split up. Bhaijan and Rubi Bu came to live with us. Only my sister had been born then, and overnight a one child family became a three child family. They were difficult times. The family had come over to flee the riots in Kolkata and my father?s low paid government salary was simply not enough. Particularly as Abba and Amma insisted that all the children should have a good education. Amma?s teaching job, plus the extra income she made from marking exam papers wasn?t enough to keep the family going. She would buy wool from the market and knit sweaters to sell for extra income. Later Khaled Bhai was born and no other children were planned. In Amma?s words, I was an ?accident.? Dadi, who had always been against her daughters-in-law going to work, saw the value of what Amma was doing and later it was Amma she used as an example to encourage her other daughters-in-law to get jobs.

Mera Sunder Sapna, the song Amma loved to sing

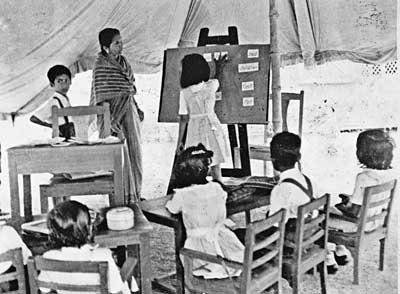

Once they moved to Dhaka, Amma wanted to setup a school in Azimpur colony. No one was supportive, but that never stopped her. Buying a tent from Rafique Bhai for ten taka, she pitched it in the middle of Azimpur playground and set up Azimpur Kindergarten. Later, in its new name of Agrani Balika Biddalaya, the school and the college went on to become one of the finest educational institutions for girls in the country.

New classrooms grew alongside the tent. There was a large classroom ?The Pavilion? which even had brick walls. When a storm in sixties blew away the bamboo classrooms, Amma sat crying in the mud floor that remained. A guardian saw her from the veranda of their house and came over to comfort her. ?Do you think it is only your school? he had said. ?It belongs to all of us, and we?ll rebuild it.? They did. The guardians and the teachers and the children had organized cultural shows and other fund raisers. This time they were determined there were to be no more bamboo walls. Each classroom had a tin roof but the walls were made of bricks.

Many years later, Amma felt she needed qualifications in psychology to run her school better. She managed to get herself a scholarship to go to Indiana University, and eventually got herself a PhD in child psychology. That was the nature of the woman. Less than five feet tall, once this diminutive woman had decided on something, there was little that could stop her. This did not always make it easy on her children. Her standards were high, and those who failed to meet them, or like my brother Khaled, who felt there were other things to life, felt the brunt of her wrath. The dedicated teacher was not always the compassionate mother. Her public contributions won her the Rokeya Padak, a state award, but with the death of her son Amma paid a terrible price. The night before he took his life Khaled Bhai told me, ?I am making things easier for you.? I had not understood the implications then. I was 14, he had just turned 21. It was a price we all paid.

His death had mellowed Amma, and I got away with much that my brother would have been chastised for. Having lost one son, she became hugely protective of the other. After the 1971 war, Amma and I went over to Kolkata to smuggle my sister and her family out of the country. It was my first taste of India and Amma and I used the opportunity well. Kolkata was the cultural capital of India and we would see three films a day, and the occasional play.On our return to a free but unsettled Bangladesh, we found things were dangerous, and there were no set rules. Once, when I needed to negotiate with some hijackers who had stolen our car, this tiny woman insisted she would stay with me and be my bodyguard.

Amma and Rahnuma by Khaled Bhai’s grave

Amma and Rahnuma by Khaled Bhai’s grave

Her protectiveness had its own problems, and as an adult, when I rejected her choice of a homely bride and found a partner of my own, she did all in her power to break up our love. Rahnuma and I stuck together despite it. Though Amma later relented, our relationship had been severely tested, and came precariously close to breaking point. Amma was strong and feisty, and didn?t take being challenged too lightly. Plucky, headstrong, and hugely energetic, she nurtured whatever she loved with a passion. Till she was 80, she would go to college everyday, ensuring that it ran smoothly.

I had gone to UCLA for the Regents Lecture. It was in LA that I got Rahnuma?s message that Amma had been taken to hospital. Apamoni, the ever dutiful daughter, now a retired doctor in London, had rushed to Dhaka to nurse her. She told me that things were stable, and I needn?t hurry back. I went on to Florence where I was conducting a seminar. Rahnuma?s second message said Amma was slipping. It was a very long flight back. My nieces Mowli and Sofia got a last minute Emirates flight and we met up in Dubai. An hour?s delay at the airport, the delay at the luggage belt on reaching home and the rush hour traffic became unbearable as we wondered whether we would see her alive. Amma wasn?t going to give up that easily. She wanted us around, and her face glowed as she saw the three of us. Fariha, my youngest niece, arrived the next day.

Fariha

Fariha

Amma at Sofia’s wedding

Amma at Sofia’s wedding

Amma and Mowli

Amma and Mowli

Amma and Sofia’s husband David

Amma and Sofia’s husband David

My nieces got out the family album, and through the pain, she peered through the photographs. As she looked at a picture of me, Fariha asked ?Who are you looking at?? The face broke into a smile. Frail, but distinctly a smile. It is wonderful how the tiniest of movements transforms a face. She whispered my nickname ?Zahed?. Later as she strained to lift her hand to stroke me, Fariha joked, ?Grandma, pull his beard.? Another smile and a whisper, ?Beard?? Later when she stroked me again, Fariha repeated her joke. Another impish smile and the word ?Pull?? Those were the last three words she ever spoke.

Apamoni had toiled ceaselessly to take care of her. Rahnuma had run ragged with errands, her grandaughters stayed up all night giving her water, changing her clothes, checking the oxygen pressure, coaxing her to eat and put on the nebuliser. Hameeda and Zohra both knew Amma well. They bathed her, combed her hair and nursed her, trying to interpret every gesture. Delower, whom Amma saw as a son, was omnipresent and kept the ship from sinking. Dulabhai, my brother-in-law, also a retired doctor, kept vigil from afar. But it was me that she longed for. This was not the time to dwell on patriarchal politics. I was losing a person who loved me beyond reason. With all my traveling, I had always wondered where I might be, when the time came. I needn?t have worried. Amma waited till I returned.

After many rainy days, with Chittagong in a deluge, the sun shone through this morning. Amma didn?t like 13. Saturdays were bad. Thursday was the best day of the week. At 8 this morning, Thursday, the 14th June, carefully sidestepping a 13 and a Saturday, with the sun glistening on her favourite champa tree, Amma chose to say goodbye.

She was 83. In those last few days, I saw my mother in a way I hadn?t before. I knew the softness of her skin, every little mark on her face, the shape of her tiny feet, the wrinkles on her fingers. As I carried her to the wheelchair, or moved her up the bed, I felt her weight against my body. I knew how it felt to be lovingly stroked by a hand that had barely the strength to move.

Her janaja was at the Takwa Masjid in Dhanmondi. My colleagues at Drik and Pathshala, our Out of Focus children did all that was needed. They would have borne my grief if they could. Many years ago, I had stood in the same mosque during Abba?s janaja, on an Eid day. We then went to her school. As the long line of students, teachers and well wishers from all over Azimpur walked past to take one last look at their beloved Boro Apa (big sister), I walked across to the classroom where I had studied. Through my tears, the benches and tables looked tiny now. Sitting on the bench and looking up at the blackboard I could hear Boro Apa?s footsteps on the corridor.

The grave in the New Azimpur Graveyard, had been bought in 1970, when Khaled Bhai had died. We had then bought three plots, for Amma, Abba and Khaled Bhai. The plot in the centre had been empty. I lowered Amma into the grave. She herself had bought the shroud and had it washed with Aab e Zam Zam, the holy water from Mecca, in preparation for this moment. The white shroud glistened against the dark clay. Our relatives and friends, Ammas students spanning sixty odd years, my own students and Amma?s numerous admirers were there. They carried the wooden Khatia, lit the incense, scattered rose water. They shared our loss.

I remembered the finality of the knot at the ends that I myself had tied. Neat rows of bamboo stakes were placed diagonally across the grave, shielding her body from the earth that was going to cover her. Bamboo mats were folded over the stakes that sealed her in. Then we all took turns to cover her with earth. After the munajat (prayers), as I walked away, I imagined my mother in between her husband and her elder son, reunited in death. I could hear them calling out to me ever so lovingly. ?Zahed?.

Dhanmondi, Dhaka

14th June 2007.

Chalking up Victories

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

At 17 Mozammat Razia Begum is older than most of the girls in her class at the Narandi School. She was married at 15 but her husband abandoned her.

?If I had been educated he would not have been able to abandon me so readily, leaving me nothing for maintenance,? she says. The marriage of young girls without proper contracts – followed soon after by abandonment – is a serious social problem in Bangladesh. Razia blames her parents. ?My parents were wrong to marry me off so young. If I had a daughter, I should not let her marry until she was at least 19.?

The school Razia attends is one of 6,000 non-formal village schools set up by BRAC – the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee – exclusively for pupils who have never started school and those who had to drop out. Three-quarters of the 180,000 pupils are girls. Although married girls are not normally catered for, exceptions are made. Many of the teachers are women: parents in Bangladesh frequently keep their daughters away from school if teachers are male. And each BRAC school is situated right in the community: if schools are far away parents will not let girls attend. It is not acceptable for girls – especially those past puberty – to walk about the countryside in this devout Muslim country.

?I am fortunate to be here,? says Razia, looking round the schoolroom with its tin roof and walls of bamboo and mud. She had to fight to come, though. Her father believes that a woman?s place is at home. ?Had I been a boy,? she said, ?my father would surely have allowed me to study.?

Razia?s own mother was married at 12 and, like her oldest daughter, had no say in the matter. ?I want my sisters? lives to be different. They should study and be given a choice about their marriage. Husbands will not dare to treat an educated woman badly.? On this subject, Razia becomes quite animated.

Razia would like to go on with her studies after she has completed the BRAC course. During the two-and-a-half hour daily session – which is timetabled to fit in with seasonal work and religious obligations – she learns literacy and numeracy, as well as enjoying activities such as singing, dancing, games and storybook reading.

BRAC have had a remarkable success in keeping the drop-out rate from their schools to five per cent and graduating 90 per cent of their students into the formal primary system. This proves that the obstacles to girls? education – even in such a poor environment – can be overcome.

As for Razia, her experience of life has forced her to question many things she once took for granted – such as the need to get married. She does not wish to marry again. And many other girls have begun to question the restrictions imposed on them. More of them want to be teachers – like their own teacher – or doctors. Razia says: ?I tell my sisters to study well and get a job. If they get a job they will be able to do as well as men and men will respect them.?

First published in the New Internationalist Magazine in Issue 240

Amma and Dulabhai

Amma and Dulabhai