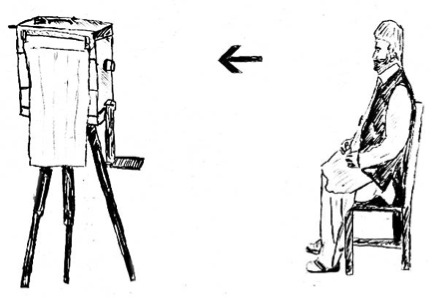

The Afghan Box Camera is a simple box-shaped wooden camera traditionally used by photographers working from a street pitch, who produce, by-and-large, instant identity portraits (aks: ???) for their clients. In Dari the camera is known as?kamra-e-faoree ().which means ‘instant camera’. It’s also less frequently called kamra-e-faoree-e-chobi (instant wooden camera) or kamra-e-chobi (wooden camera). In Pashtu the camera is sometimes referred to as da lastunri kamra (sleeve camera: ??????? ?????) because of the sleeve on the side of the camera that photographers insert their arm into.

Continue reading “ABOUT AFGHAN BOX CAMERA PHOTOGRAPHY: KAMRA-E-FAOREE”

Continue reading “ABOUT AFGHAN BOX CAMERA PHOTOGRAPHY: KAMRA-E-FAOREE”

Tag: livelihood

Beri Bandh 2: Sadek City Model Town

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

The accident had changed things, and rather than see it as an impediment, I decided to make it a feature of my work. So on the 2nd Monday having been to the hospital for my regular physiotherapy, I revisited the scene. Walking down the narrow alleyways in between the line rooms in Sadek City Model Town (I have no idea who Sadek is), I met up with some women and two girls (around 8-10). They wanted pictures taken, and wanted to art direct the photos. So I was rapidly being given instructions, which changed as every new person joined what had become a rapidly growing crowd.

The act of taking pictures wasn?t so easy. With my right hand having low mobility, I had only taken my compact, and was taking pictures with my left hand. That?s when you realise that cameras are not designed for left handed people. Still, with a small camera you can improvise. Soon they decided they needed prints, so the two girls dragged me down to the local studio. It was a longish walk and I had wanted to stop several times to take pictures, but only managed a few times. The two girls were tough task masters. The guy in the studio was asleep, and a bit grumpy for being woken up. But he didn?t make prints himself. He would gather the images and send it off to a nearby lab, so we returned empty handed. I promised I?d bring prints back the following Monday.

I was then taken round and introduced to the other families, and eventually, they found a kitchen where they could pose as they wanted. The girl cooking was even younger than them, and the two art directors quickly took control. The shaft of light and the smoke were just lucky ingredients. Slowly the residents of Sadek City Model Town opened up to me. Some were still suspicious. Was I going to report to the government? Would this result in another eviction? What was I going to do with these pictures? But soon we were friends. A little baby that came to me, refused to go back to her mother. I was now a family member! The houses (8 foot by 8 foot rooms) cost 1100 Taka a month to rent. Per square foot, that was almost twice as expensive as our flat in Dhanmondi! And that was excluding gas. They spent 30 Taka a day on firewood, so it effectively cost 2000 Taka per month (about 20 Euros) a month for that one room. They did have electricity (sometimes), and there was a nearby tubewell where they could bathe and draw water from. The common loos did have long queues, but were considered adequate. This was a transit point they explained to me. The place where people stayed when they first came to the city. Once they found better work, they would move on. To brick houses, with piped gas. The tin roofs meant the rooms were like ovens in the summer and a freezer in winter.

There were two storied houses too. The upper floor had a thin concrete floor, to ensure the floor didn?t leak. I was surprised that a bamboo walled structure could have a concrete floor, but it seemed to work. Narrow wooden stairs led to the upper floor. It was a tinder box anyway and with these narrow exits, there would be no escaping if there was a fire.

They had arrived from all over the country, though many were from Barisal, a coastal region in the South. The men would ride rickshaw vans or work as day labourers upon arrival. ?All you needed was a basket and a spade. If you worked flat out from 8 in the morning to sunset, you could earn 200 Taka (about two Euros) a day. You wouldn?t get work every day, but enough days in a month to pay for the rent and food.?

On the way back, I came across the barber shop. One of many I?d seen that day. It didn?t look too interesting at first, until I saw the pigeons flying. They were flying, eating, shitting, without the slightest trace of concern, or fear. This was obviously their home, and the clients who came in to barber were the intruders. The barber had gone off leaving the client in the chair, and the pigeons were just getting on with their lives. The barber?s younger brother was there and explained that earlier there were more birds, including parrots. But it had become too much of a hassle, so now the barber only kept pigeons.

I had started later than I had hoped, and being a bright sunny day, I was in the glaring sun much of the time. I had to be careful with my framing in this very hard light. So I did most of my work indoors, or in the narrow corridors where the was little direct sunlight. Ideally I would have waited for the lovely afternoon light that accompanies winter, but my pains were beginning to take toll.

As I headed back I went through Rayerbazaar, and the people I had photographed last week all flocked. I managed to avoid tea, but was given a cup of fresh cow?s milk. One doesn?t usually get fresh milk these days, so this was a treat. The conversation veered to the local mafia and what some of the locals were getting up to. I left promising to bring back some prints next Monday. I realized, I would need to make a LOT of prints for that day. I then came up with the sugar cane juice man from last week and he squeezed two special glasses for me. As I was buying some water chestnuts, a guy passing by, told me of the Kali (Hindu Goddess) puja that was taking place nearby. I followed the directions to a narrow alleyway, where the Goddess was in all her splendour in a raised platform at the end. The singing, dancing and firecrackers just added to the atmosphere.

River and Life

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

They meander and glide. They unfurl with the rage of monsoon fury. Quietly they flow in the misty winter morn. Rivers thread the fabric of our land. Embroider patches of fertile delta. They are the nakshi kantha of our rural folklore. Life giver, destroyer, enchanter, they have inspired the greatest myths, formed the tapestry for the most endearing love songs. Our Bhatiali has been shaped by the lilt of the boatman?s lyrics drifting across the waves.

It is this fluid, amorphous, ephemeral and elusive visual that Kabir tries to hold in his rectangular frame. It is a frame heavy with the burden of its task. The rivers that float like a gossamer across the green delta hold untold stories. Tales of strife and endurance. Of the fullness of life. Of abundance ebbed, and anger unleashed.

Kabir finds the rapidly disappearing sailboat drifting in the late afternoon light. The extinction of this species owes not to the depletion of its habitat, or to the oft-blamed climate change, but the advent of technology. Oil guzzling, deep tube well engines have unseated the wind from its traditional role.? A lone sail, bright red and taut against a blue sky defiantly throws a gauntlet to the mechanized usurper.

Swirling swathes of jute cleanse themselves in the very water that nurtured them in their youth. Wispy traces of boatmen recede into the darkness of dusk. The cool blue light of the evening sky wraps itself round a homebound farmer. Barefoot women, walk home after a day?s work, like a string of pearls along the sandy shores of a receding river. Parched river beds, like a desert amidst the oasis, make horizon-less paths for weary travelers to tread.

Fishermen, silhouetted against a brooding sky, cast their nets more in hope than in expectation. Overfishing of uncared for rivers, bloated with toxic waste, yield little to those who have made the river their home. Indeed it is their ancestral home. A liquid home that knew no government deeds, and obeyed no official maps. But the rules have changed. City folk whose feet walk only on the cool marble of urban dwellings own fishing rights to rivers they may never have seen. The fishermen who were raised in these waters are now outlawed in their own turf.

Still the river gives. Joy and thrill to the racing crews that steer swiftly through the monsoon breeze. Respite to the sun baked skin of naked boys, sari clad maidens and heavy hoofed buffalos. Turgidity to the parched leaves of the newly planted grains of rice. Looming clouds in azure skies to the poet who longs for whispering words. Winding arcs of sinewy lines to the painter?s canvas in search of form.

The great rivers, once bountiful and brimming, have formed the supple spine of our deltaic plains. Choking in silt, poisoned by waste, waterways throttled by land grabbing encroachers, the lifeblood of our deltaic plains weep dry tears as their once glistening bodies writhe in pain. It is a pain city dwellers are deaf to. A pain that short sighted politicians and profit seeking urban planners have no time for. Kabir rejoices in the vigour of the river. Is saddened by its pain. His portrait of the river shows both its wrinkles and its smile.

Photographs: Kabir Hossain

Text: Shahidul Alam

The exhibition “River and Life” by Kabir Hossain will remain open until the 17th July at the Drik Gallery II from 3:00 pm till 8:00 pm