By Rahnuma Ahmed

The starting-point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is ?knowing thyself? as a product of historical process to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory…therefore it is imperative at the outset to compile such an inventory.

Antonio Gramsci, The Study of Philosophy,

quoted by Edward Said, in Orientalism

? the institutionalised forces of industrial capitalist society…constantly tending to push the meanings of various third world societies in a single direction. This is not to say that there is no resistance to this tendency. But resistance in itself indicates the presence of a dominant force.

Talal Asad, Genealogies of Religion

?We want democracy in the family?

It was 1990. We were out in the streets celebrating the downfall of the military dictator President HM Ershad, in the week that followed the historic 4th of December. Hundreds of thousands of people had gathered. The procession snaked its way through the central streets of Dhaka, from Topkhana road to Paltan intersection, on to Gulistan. People held banners and placards which proclaimed their party loyalty or their ideals. Some chanted slogans, others sang. Bystanders stood, they waved and cheered us on, some slipped in and joined us.

Meghna, Suraiya, Hasina, I myself and several others held placards, we belonged to Nari Shonghoti, a small research-cum-activist women?s group, intermittently active in those days. One of these, ?Poribarey gonotontro chai? received the most attention. Co-processionist men read it and nudged others. Smiling, they shook their heads. We smiled back and amidst the riotous explosion of noise mouthed the words, ?And why not?? Women, too, smiled. Some nodded their heads in solidarity, others, like men, knowingly. They knew that this was one sphere ? home, marriage, sexuality, love, housework, the distribution of resources ? where transformative and egalitarian changes would be the hardest to achieve. Dilli bohut door ast. Both men and women who encircled us in that sea of people, rejoicing at the downfall of the autocrat, knew that.

One can know oneself only as a product of historical processes because, for Gramsci, ?each individual is the synthesis not only of existing relations, but of the history of these relations.? Men and women are ?a pr?cis of all the past.? And the past, that is history, is only traceable through its traces. History?s very mode of existence is in the traces.

I sift through feminist and anthropological studies of this region and beyond, to discover the ?traces? of our colonial legacy, thought to be beneficent in social senses (?women?s rights?, ?autonomy?), and to understand the institutionalised forces of the West that push us to desire marriage and family relationships that are ?singular?. In the act of doing so, I also draw the attention of self-consciously thinking sections of Bengali society towards their uncritical acceptance of the encroachment of the modernising state, in areas of social life that were previously unregulated. This act of ?compiling inventories? in order to ?know thyself? is motivated by what I think is necessary: a critique of social, economic and ideological processes working to effect modernising changes in marriage and family forms in Bangladesh.

I have no answers to the questions that you may confront when you reach the end of this piece. ?Answers?, as such, can only be the outcome of social and political struggles.

Colonial ?traces?: the dismantling of jointness

Hilary Standing, a feminist anthropologist, has examined the deep-seated changes that took place in Bengali families as a result of the growth of wage dependency in late nineteenth and early twentieth century (1991). In an excellent discussion on the transformation of landed households into wage-dependent ones, she details the encounter between traditional, culture-specific forms of income management, based on jointly-held property, and capitalist ideologies of wages as ?belonging? to the individual. The growth of the wage economy and the rise of the Bengali Hindu middle class (bhodrolok)?not an industrial bourgeoisie but a class of bureaucrats and professionals, in service of ?the demands of imperial capital??precipitated a huge ideological clash which shook the very foundation of Bengali households and families.

This transformation, part of larger historical processes, un-made a distinct way of life, only to re-make it along the contours of modernising (this includes capitalist) aspirations and material realities. In the case of the Bengali Muslim middle class, as I argue later, it extended to equally radical changes in marital forms: marriage was re-defined as being strictly monogamous, it was imbued with new meanings of being a civilising force in society.

To return to Standing?s work: drawing on her own research, and that of others?, she says, the Bengali middle class sustained rural-urban links through the joint family. A village home was maintained for several generations, and income was pooled into the joutho bhandar (common fund) from landed rents and the salaries of family members who were professionally employed. Ghor-bahir division was strictly enforced, men were assigned to the external economy, to culture and politics, and women, to the internal organisation of the household. The senior-most married woman had authority, which derived from the age and kinship hierarchy. She was in charge of the common fund, she paid servants, gave gifts, carried out charitable obligations. Young married women had authority only if there were no older married women in the household. Ghor was women?s arena and, generally speaking, men were absent here.

Families centring around jointly-held property subscribed to distinct ideologies of redistribution of financial resources. Both land and money income, from whatever source, was vested in the kinship group as property-in-common. Members were entitled to funds on the basis of their personal needs but this did not mean equal access, or equal rights. Women held inferior rights to landed property. Hindu widows were expected to eat little and only vegetarian food, to have few items of clothing. Claims to family and household resources were determined not only by considerations of gender, but also by the kinship status of its member.

In capitalist economies, Standing says, the wage is associated with an ideology of personal appropriation. It ?belongs? to the wage earner. He has the ?right? to use his earnings for himself; dispensing it to ?his? dependants?his wife and children?is something personal. Occupational achievement is individual. The ideology of the wage emphasises ?private accumulation, personal achievement and personal ownership? through ?individuating mechanisms? like banking, savings, and insurance policies. The introduction of the wage, and its accompanying ideologies of personal belonging and appropriation, she writes, created deep divisions and conflicts over ?earners? and ?non-earners?, ?productive? and ?non-productive? members. Degrees of dependency emerged within the wider household collectivity: male non-earners became defined as ?idle?, a burden to their earning relatives, while the conjugal tie increasingly moved centre-stage and began to pre-empt or challenge the claims of other family members to household resources.

Two official documents express the colonial government?s discursive and regulatory concern with the nature of the family. The first faults women for the demise of the joint family:

Devoted to their husband?s interest, the wives are jealous of their earnings being used by others, particularly by those who do not contribute to the family income. More petty feelings, less disinterested motives, such as the mutual jealousy of the brothers? wives, the quarrels of their children, etc also contribute to the breaking up of the family. (Government of India 1913, Census of India 1911, vol V, part 1, pp 50-1).

The second acknowledges ruptures in the principle of non-differentiation between family members on the basis of their ?earning capacity?. Standing says it also reveals the extent to which ?narrowing definitions of dependency? were coming into effect:

Many correspondents commented on the fact that the presence of a widow in a family was always welcome because she would cheerfully undertake the drudgery of the family whilst the extreme self-denial expected of a Hindu widow makes her support very little of a burden. But where she is unprovided for and has children there are bound to be heartburnings on account of the differences in the treatment which her children and those of her husband?s relatives receive. (Government of India 1933, Census of India 1931, vol V, part 1, p 402).

That a man should feel ?less responsible? for his deceased brother?s widow than his own wife, or a woman should consider her sister-in-law?s children as ?less deserving? than her own, are not, Standing argues, ?natural?, or ?inevitable?. On the contrary, they are the result of complex social and historical processes. These processes simultaneously laid a new emphasis on the role of wife as ?housewife and manager? of the allowance given to her by her husband, one that was framed by newly-forming ideas about women as being nothing more than mere housewives. Grouped together with ideas about women as ?consumer and conveyor? of new values and attitudes, these were ?essential? to the ?reproduction of the new middle class?.

Similar processes were at work among Bengali Muslims, albeit somewhat later. I realised this both during and after conducting field-work based research (shelved) in the early 1990s. It was something of a shock because I had been brought up to believe that Muslim notions of property and inheritance were vastly different to that of Hindus. In ?ours? property was individually owned and divisible, while in ?theirs? it was jointly held. This was reinforced by my own childhood experiences, based as it was on nuclear family living. I was born in the mid-fifties, my father was a government employee in what was then West Pakistan, and I grew up far away from uncles, aunts, cousins and extended kin, except for a brief three-year period that was caused, in officialese jargon, by my father?s ?transfer? to East Pakistan, in the early 60s. But I must not be too harsh on myself. My life in independent Bangladesh from 1972 onwards, and knowledge about Bangladesh society and culture that I gained later?through studying at the university, conducting research, being part of intellectual/activist circles?had led me to believe that the pooling of family income was a mere ?cultural? practice (for instance, similar to marriage rituals like gaye holud), that it was optional, since we were, after all, governed by Muslim laws. This was, and still is a commonsensical assumption in learned circles and, I contend, is a result of not seriously engaging with the nature of colonial rule, and the manner in which colonialism, to paraphrase Talal Asad, has destroyed old options, and constructed new ones, and set into motion historical trends that are ?irreversible?. More recent research persuasively argues that in the interests of controlling and regulating the lives of its subjects, the British colonial state had codified ?the laws of the Koran? for Muslims, and the laws of the Brahmanic ?Shasters? for the Hindus. It was the colonial state?s application of Muslim law through its new system of courts that enabled Muslims to freely decide, or compelled them to order their affairs, in accordance with the principles of Muslim family law.

My fieldwork based research on the Bengali Muslim middle class had gathered family and household data of both the present and 2-3 preceding generations. I had also read autobiographies and autobiographical essays written by first, second, and third generation middle-class men and women: Tamizuddin Khan (1889-1963), Principal Ibrahim Khan (1894-1978), Abul Hossain (1897-1938), Kazi Motahar Hossain (1897-1981), Abul Mansur Ahmad (1898-1979), Abul Fazal (1903-1983), Dewan Mohammod Azraf (1908-1999), Abu Jafor Shamsuddin (1911-1988), Syeda Monowara Khatun (1909-1981), Sufia Kamal (1911-1999), Kamruddin Ahmed (1912-1982), Akhtar Imam (b 1917), Jobeda Khanam (1920-1990), Umratul Fazl (1921-2005), Zobaida Mirza (1923-1993), MR Akhtar Mukul (1929-2004), Anisuzzaman (b 1937), and that of many others. My own fieldwork data, the autobiographical accounts, and also the critical scholarship that I cite above, have convinced me that before British colonial rule, jointness was family, that this was equally true for both Hindus and Muslims. Its historical ?traces? are to be found in the autobiographical writings. In these, while presenting and interpreting their life experiences, some of the men and women speak from a sense of bewilderment and loss at rapidly-dissolving priorities, while others focus on a newly-emerging set of personal and familial commitments, suitable and appropriate to the demands of a new social order. In the novels of writers like Mohammad Najibar Rahman (1860-1923) and Kazi Emdadul Haq (1882-1926) one comes across fictionalised accounts, often justificatory, of the social changes that were rapidly becoming inevitable.

My fieldwork data and the autobiographical writings I cite above, reveal something else. The growth of the wage economy had not only made kinship dependencies among Bengalis problematic, as Standing argues, but that in the case of the emerging Bengali Muslim middle class, it was accompanied by decisive changes in the form of marriage. The previous ?system? of marriage included monogamy, serial monogamy and polygamy. It was marked by flexibility (I do not use this word in any value-loaded sense). The new system, one that grew out of social upheavals accompanying middle-class formation, was strictly monogamous, it idealised marriage as involving ?commitment for life?. This was essential to the middle class? collective sense of self, that of being civilised, and of being a civilising force in Muslim society.

Colonial ?traces?: a civilised marriage as crucial to class identity

I have argued in an article published elsewhere (The Journal of Social Studies, 1999) that colonial representations of the status of Muslim women had a determining character in the imaginings of female emancipation. Colonial narratives essentialised ?Muslim?-ness; simultaneously, it ascribed Muslim women?s poor and miserable condition as being a consequence of ?seclusion?, and ?polygamy?. Both were regarded as archaic and barbaric, as being incongruent with modernity. Bengali Muslim intellectual forerunners largely accepted British characterisations of purdah and polygamy as essentially Muslim, that is, specific and universal to Muslims. Women?s freedom and emancipation was primarily imagined as doing away with seclusion and polygamy. These discourses constituted middle-class identity?its subjective and collective sense of self?which distanced its members from the uncivilised (o-shobbho), the ignorant, the large masses of poor, whose marriage practices in emerging middle-class discourse became characterised as kono thik-thikana nai, kokhono ere dhore, kokhono tare ccharey (?their marriages lack substance, living with this one here, casting off that one there?).

Gradually, marriage became binding and obligatory in new ways. It came to signify men?s worth?in their individual capacity, as a husband?as economic actors. New social concepts emerged, a husband was defined as one who had the ability to ?raise? a wife (bou palar khomota). This helped to infantilise women as wives, it lent credence to the idea that housework was not laborious, that a woman was a ?mere? housewife. The new wife was re-defined as a moral person, her task was to re-construct marriage, and the home, as a sexually sacrosanct space. Marrying-for-life was linked to notions of female sovereignty and freedom. Nowsher Ali Khan Yusufzai?s phrase (1890), although (mis-)directed at marriage practices among the Muslim aristocracy of his time, captures this beautifully: ?two lionesses cannot live in the same forest? (ek oronne dui shinghinir baash kokhonoi shombhobonio noy). Marriage no longer meant belonging to a wider collectivity, instead, it was re-defined as being an exclusive conjugal bond. This was reflected in changed modes of referring to one?s wife, instead of apnader bou, ?your daughter-in-law?, to ?my wife?, amar bou. Corresponding changes were to emerge in women?s choice of words: her husband was no longer ?your son-in-law?, apnader jamai but amar husband. Children too came to belong to their parents, amar cchele, amar meye. Earlier practices of addressing one?s wife, as Laila?r ma, or Abuler baap, have become the language of poor, uneducated people, people not conscious of their worth as individual persons. As a marker of civilisational status, it has become uncivilised, if not loathful, for modern Bengali Muslim women to voice the opinion that a co-wife means a co-sharer in domestic work. (Except, of course, as a joke). These new meanings of marriage coalesced with other ideas?education, science and rationality?and became central to class identity. They contributed to feelings of moral superiority, to the notion that providing leadership, social, political and intellectual, was a natural right of the educated classes.

I now come to the present. A general point that I would like to raise is that, progressivists, secularists, developmentalists, those belonging to the women?s movement, and also, members of the left?mostly, overlapping schools or ghoranas of thought?uncritically accept middle-class practices and ideas of marriage as being emancipatory for women, as a mark of progressiveness, as superior (?Class struggle is a struggle over morals.? Surely the words of the historian EP Thompson, famed for his ?history from below? approach? But I seem to have misplaced the reference). Uncritical acceptance on the part of the women?s movement in Bangladesh is understandable?although not acceptable, as most organisations claim to represent ?all? women?since it largely subscribes to, what Meghna Guhathakurta has described as a ?development[alist] outlook on the women?s issue?, one that she is quick to point out, is ?a-historical? (2003). This raises several problems, but let me say at the outset that what I refer to as ?the? women?s movement in the singular, is actually heterogeneous, comprising various organisations and groups with different aims and objectives, and different histories of action. However, notwithstanding these differences, I still think that the broad outlines of my critique are valid.

First, by not examining the class-ed basis of monogamous marriage, the movement is unable to conceptually deal with the issue of female subjection within middle-class marriages. To express it somewhat differently, it is ill-prepared to conceptualise modern forms of women?s subjection, since the unquestioned assumption is that modernity per se is a historical condition that emancipates women, or moves them forward, closer to emancipation. Unlike the ?backward? essence that characterises the condition of women, particularly, in Muslim societies.

Second, by not examining the class-ed basis of monogamous marriage, it is able to operate on the notion of a ?universal? (national) female experience. What is specific to class gets generalised across all classes: monogamous marriage is in all women?s interest, and equally so. It ensures security for all women, and equally so. Subaltern marriages, in my eyes (I say this tentatively, in the absence of serious research), are flexible, they combine monogamy, serial monogamy, and polygamy. Of course, processes of impoverishment, eviction from rural land, uprootment, severe unemployment and the inability to provide for oneself and one?s family members hit both poor men and women. And, of course, there is an undeniable gender dimension: wives, who have even lesser claims to social resources than their husbands, are often deserted and left to fend for themselves and their children. However, despite contemporary social processes of impoverishment and pauperisation (?the beggary of labour?) and their impact on marital stability, I still think that subaltern marriage practices and ideas are distinct and thereby, analytically separable, from that which exists among the privileged classes. To reinforce what I have just said, I think that ideas and practices of marriage in Bangladesh, and its history, is fundamentally different in class-ed senses. The women?s movements? unexamined rooted-ness in, and loyalty to class ideals, accomplishes several things. It perpetuates the idea that subaltern marital practices are a ?social evil?, in need of correction. By isolating marriage from its class-ed history, and from class-ed realities, it also, in effect, puts the cart before the horse. After all, under capitalism it is not the practice of a strictly monogamous marriage that will ensure poor women a home and three meals a day! The movement?s emphasis on legal reforms helps to ?obliterate? material differences, and the unequal strength to counter dominant ideologies, that exist between women. Through this process, the issue of equitable distribution of social resources, and the fight for social justice gets sidelined.

Third, the movement?s inability to historicise marriage by placing it within the broader context of love, sexuality and family formation means that, by default, it takes up a socially prescriptive and prohibitionary role. That hijras were a part of traditional social life, visitors at each childbirth in the locality, has been relegated to the margins of middle-class understandings of sexual differences. I remember asking a young man who belonged to one of the small campus-based left groups, ?What will happen to transgender people after the revolution?? His answer was immediate, ?They will be surgically operated on.? That all hijras might not want it was not at issue. (Let alone the fact, that small, but increasing numbers of men and women, in other words, those not born as hijras?are willingly undergoing sex change operations, mostly in Western countries, but also in neighbouring India, and that this bespeaks of a social phenomenon that should compel us to re-think our ideas). Hijras are an abnormality, in need of correction. I have come across similar ideas among women belonging to the movement, ideas that are based on compulsory heterosexuality, but un-acknowledged as such.

Other marriage histories: at the margins

I now turn to ?other? histories of marriage, in particular, to a specific practice of marriage developed and practised by Naxalites, the pro-Maoist trend of the communist movement in Bangladesh, committed to capturing state power through armed struggle. Nesar Ahmed has performed an invaluable task by interviewing women who were active in underground Naxal politics in the 1970s. The tape-recorded and transcribed interviews have been published in Jibon Joyer Juddho (2006).

In 1970, the East Pakistan Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) presented itself as the East Pakistani counterpart of West Bengal?s Naxalites. After committing itself to a programme of organising guerrilla action against class enemies in the countryside, the party went underground. Purbo Bangla Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) was also committed to a similar programme of armed struggle; in popular usage, its members were known as ?Nokshali?. Many of the leaders, and a large number of its followers, both men and women, came from the middling ranks of rural and mofussil society.

The interviewed women (they include both Muslims and Hindus) speak of their family background, why, as women, they were particularly drawn to ?the? party, what they read and discussed in study circles, and of other experiences too: leaving village homes to join the class struggle, the nature of ?their? party activities, participating in armed action, getting married and giving birth to children, giving them away to be raised by poor families supportive of the party?s ideals and programmes, leading ?hidden? lives in party shelters, and the hardship of living on meagre amounts doled out by the party to its members. They also speak of familial, marital and employed life after the party renounced its programme of armed struggle in 1979, in their words, after they returned to ?social life?. Several of the women interviewed were party members whose husbands had gone underground while they struggled to earn a living, run a household and raise children.

Nokshal marriages too, were strictly monogamous, but in other aspects, they differed significantly from dominant Bengali Muslim middle-class practices. I read and re-read the interviews, motivated by my desire to gain an understanding of the politics of marriage in Bangladesh.

This is what I glean and put together from the interviews: the ceremony itself was simple. Several party members would be present. The marriage document was a written piece of paper drafted by party office-holders (women referred to it as ?the form?), the names of the two members to be married were written down. Party members, including the couple who were to be married, would sit and discuss party ideals. At the end of the discussion, they would vow to remain committed to these ideals, even after marriage. Marriages (bie. In Bangla, no distinction is made between a ?wedding?, the ceremony, and ?marriage?, a social relationship) were generally held in ?shelters?, i.e. village homes of local party sympathisers instead of being held in the bride?s home, as is the general custom among Bengali Muslims and Hindus, where her father and senior kinsmen give her away to the groom and his family. After exchanging flower garlands, they would shake hands and sign on the party form. The couple were then pronounced married.

Generally, a meal followed. Aruna Chowdhury, who was a matriculate when she joined the party says, ?We ate gur (molasses, brown sugar) and bread, that?s all we had, bas, that?s it.? She adds, ?My wedding was an ideal one. I was wearing an old sari, torn in places.? Dipti, a fulltime worker and a cell member, got married slightly better-off than Aruna. ?Comrade Wajed?s wife was present, as my friend. She went and bought me a sari, a petticoat, a blouse, oh, it was just a simple cotton sari, and a bar of soap.? But some of the meals were not as austere. As Aruna recalls, ?Some marriages were ?gorgeous? affairs, cows and lambs were slaughtered. The village people arranged everything, at least that?s what they said. Well, I said to myself, obviously people don?t love us as much, we are not big leaders.? Reflecting on these tangible differences, she says, it?s like the ghost stories you hear as a child. You grow up and read about science, about science fiction, and you know it?s not true. But still, when you return home at midnight, just beneath the mango tree, you feel scared. That?s what marriage is like. Us Bengalis, we start dreaming about getting married right from childhood. Materialism helped me to get rid of these ideas.? She adds, ?I?m not angry about those gorgeous marriages. They did take place, that?s why I bring it up.?

Naxal marriage deviated from earlier traditions which insisted that revolutionaries should not get married, a heritage shared by the communist parties of undivided India. Earlier, said Aruna, the Party had been ?rigid? on matters of love and marriage. ?But when we entered the Party we discovered that political marriages were taking place. Party workers were marrying other Party workers.? Ismat ara Rita, a 17 year-old matriculate who went underground to escape her father?s pressure to marry, to prevent her from entering revolutionary politics says, marrying within the party was particularly necessary for women. ?There was no question of women Party members marrying outsider men. After all, this is a patriarchal society, and men do have some influence on us.? Men too, she maintained, married only women party members, a wife who was not ?attached to politics? would have led to problems at home. But there were exceptions, as other interviews reveal. Aroja Begum?s husband was not a party member. ?He didn?t understand these things. But he never said no to what I did.?

Party-based marriages underwent a strict vetting procedure, casting party leadership in the role of ?guardians?. Dipti recounts her experience: ?Comrade Zakir Hossain Hobi was in charge of the district committee. He asked me one day, he said, if you don?t have any objection then I will forward a proposal to the Party.? Dipti, who had faced unwarranted proposals from other party comrades, to the extent of suffering a near-mental breakdown (?I had come to do politics?), had finally decided to get married. She says: ?I agreed. After that, the district-level Party said, okay, let?s see. By then I had been assigned to work in Kaliganj. I began working there, and I was told, you will now be tested. When Hobi asked the district committee for their opinion, they said, the time is not ready yet, we will think about it. During this period of testing, I was assigned to Chuadanga, in charge of the Party?s cell, while Hobi worked in Kaliganj. We were asked to not meet each other, nor write any letters. This was the test, they said. This continued for a year. After that, they finally gave their approval. They were convinced that we really liked each other, that it was not a mere infatuation. They said we could get married.?

The Naxal form of marriage was political in other senses as well. The marital union of two people was approved by the party on the condition that their commitment to politics?revolutionary party politics?overrode all other commitments. Further, it did not conform to legal definitions, and side-stepped religious conventions. These ideas seem to underlie a question that Nesar Ahmed asks Rita. ?Conventional marriages are performed by moulobis and moulanas, it lends them sanctity. That?s a common sentiment. But your marriages were different. How did the general public react to it? How did they view it? After all, marriages mean kolma-kabin.? She did not respond to the question on public reaction, but instead spoke of how her party had viewed it. ?The Party?s sentiment was that this kind of marriage was ?better?. It is similar to registered marriages that take place before the kazi because even though the word kobul is not uttered, it is ?written?.? She added, ?This is an advanced-modern era, Party marriages were seen as fore-runners to marriages of the future.? Her words had a ring of history.

With the renunciation of the politics of armed struggle in 1979, the distinctive marriage ?system? developed and practised by the Naxalites was abandoned. Women comrades were asked to return to their families, or to marry and settle down. Thus began, what Nesar Ahmed terms, the ?domestication? and ?house-wifisation? of Naxal women. But not all Naxal women agree with him. ?There was no other option.? The party was organisationally shattered, many of its members were either dead, or imprisoned. As one of them put it: ?The Party?s decision was right. If it had been otherwise, women comrades would either have been killed, or forced into prostitution. The Party?s policy of armed struggle, of annihilation of class enemies meant that…, well, we had created enemies in our own villages.?

I do not wish to pursue the question of whether the party?s decision was right or wrong. Instead, I want to turn to Ismat ara Rita?s words, ?this is an advanced-modern era.? I want to place these in the context of the tradition-modernity framework that frames women?s rights issues in Bangladesh, one that is conceptually unable to deal with the issue of colonial power. I discuss work that does, so that we can know ourselves better, and more critically. In the section after that, I return to Nesar Ahmed?s words, ?Marriages mean kolma-kabin? because I want to delve deeper into the institutional moorings of marriage?into the legal definition, and religious conventions prevalent in Bangladesh?and the ideas through which compliance to legal inequalities is secured. Here, I turn to my own personal history, to an incident which I think can be teased out to unravel processes of subjection that are at work.

Colonial-modernity: processes of Islamisation

The women?s movement in Bangladesh, as I said earlier, is intellectually ill-equipped to deal with the issue of women?s subjection in modernity. Lata Mani, a feminist historian of West Bengal, in a discussion on sati thinks this is tied to our understanding of colonialism. Regardless of how scholars view its impact on India?s transition from feudalism to capitalism, they all agree that ?colonialism held the promise of modernity,? that it gave rise to ?a critical self-examination of indigenous society and culture.? Even the most anti-imperialist amongst us, she says, has been forced to admit that colonial rule had ?positive? consequences for certain aspects of women?s lives, if not in practical terms, then at least in the realm of ideas about ?women?s rights? (1989).

In Bangladesh, intellectual-activists belonging to (overlapping) schools of thought?left, progressivist, secularist and also those in the women?s movement?subscribe to a simplistic and over-generalised account of women?s history. In some accounts, large periods of history are characterised as unchanging in the ?oppression of women? (?thousands of systems of oppression towards women continued in male-dominated societies for thousands of years,? Badruddin Omar, 2003). Pre-colonial Bengal is often characterised as belonging to ?the dark ages of medieval history? (Ayesha Khanam, 1993). These highly emotive accounts of history are inter-woven, they feed into each other, warding off attempts to gain a critical understanding of the nature of colonial rule, more specifically, at the colonial government?s codification of laws (in the case of Muslims, Qur?an and al-Hidaya, whereas in the case of Hindus, specifically Brahmanical interpretations of the Shasters), and its use of legislation as a technique of ruling.

But before turning to that, I will look at pre-colonial society, at the principles of social organisation in rural areas that prescribed marriage, family life and household formation. Talal Asad, in a study of the Punjabi Muslim family, has argued that ?differences in the forms of family organisation? of rural Hindus and Muslims during Sikh rule were ?negligible, or non-existent,? and that Islamic laws (Hanafi) were only followed by Muslim communities in urban centres, characterised by a market or money economy.

Asad writes, in pre-colonial villages of Punjab, rights to landed property were distributed in accordance with definite principles within a precise kin group. It was, in a certain sense, ?owned? by a lineage, but held and worked by the joint family. It was the joint family, as a whole, that comprised the work and consumption unit. The head of the local descent group (equivalent to Bengali notion of goshti) was the undisputed controller: all members together formed a single economic and legal unit. The oldest male member was its head. If relations between sisters-in-law grew strained, a separate hearth might be set up, the wife then would prepare meals for her husband and children separately, but food rations would still be taken from the common stock (the joutho bhandar). However, no changes took place in farm work, and male members continued to till the land together. Marriage was an affair that involved the entire joint families of bride and groom. It did not mean the setting up of a separate hearth, on the contrary, the daughter-in-law was inducted into the joint household. Bride-price (in Bengal, pon) was given by the groom?s family to the bride?s; with its transfer, the wife belonged to the husband?s joint family. A widow, whether chaste or co-habiting with her deceased husband?s brother (debor) or a patrilineal cousin was entitled to life-long maintenance, losing this right only if she were to re-marry outside the descent group.

The colonial state, argues Asad, initiated a ?process of Islamisation? by gradually applying the principles of Islamic law which meant that Muslims now either ?decided, or were compelled by the courts, to order their affairs in accordance with the principles of Muslim family law.? One of the results was that women, as widowed daughters-in-law, lost their customary rights to maintenance by their in-laws.

Michael Anderson in his article, ?Islamic Law and the Colonial Encounter in British India? (1990), draws on more recent theoretical tools that help us to appreciate what happened in the early stages of colonial rule. The colonisers, he says, were perplexed at the multiplicity of local customs and practices, at the many forms of legal authority that existed. In their ?quest to establish a definable and reliable relation between government and the governed,? they found a solution in law, and legal texts. Anglo-Muhammadan jurisprudence was born in the first century of colonial rule. I quote from Anderson:

The Hastings Plan of 1772 established a hierarchy of civil and criminal courts, which were charged with the task of applying indigenous legal norms ?in all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste, and other religious usages or institutions?. Indigenous norms comprised ?the laws of the Koran with respect to Muhammadans?, and the laws of the Brahminic ?Shasters? with respect to Hindus. Although the courts followed British models of procedure and adjudication, the plan provided for maulavis and pandits to advise the courts on matters of Islamic and Hindu law, respectively. By the early nineteenth century, the system of courts had been expanded, a new legal profession had been established, and a growing body of statute and court practice extended the influence of the colonial state.

It was through colonisation that we began to lead lives commensurate to the demands of a modern state (more apt would be, what Asad terms elsewhere, the ?modernising? state). The distinguishing feature of a modern state, he says, is that instead of being a dominant segment of society, it becomes ?the dominant mode of organizing its life? through the momentous new categories of ?public? and ?private?. In the modern state, the social conditions of one?s existence, including their relative advantages, are determined within the domain organised as the state. The Law is one of these conditions. And this is why, it is only in the modern state that one comes across ?struggles within and about various legal categories that constitute working-class politics, the politics of gender, the politics of sexuality, and the politics of procreation.? (1992). In the case of India, as Anderson points out, it was through the legal techniques of colonial rule that the category of ?Muslim?, often ?Mohammedan?, acquired ?a new fixity and certainty,? in contrast to previous identities that had been ?syncretic, ambiguous or localised.? Each individual was now linked to ?a state-enforced religious category,? litigants were now ?forced to present themselves as ?Muhammadan? or ?Hindu?,? as courts struggled to accommodate diverse social groups within these two categories. The colonial mode of governance also transformed personal law into a ground for organised political struggle, it helped to mobilise a Muslim identity that was opposed to colonial rule.

And, I add, it was colonisation and its legal technologies that created the conditions for older inequalities to give way to ?specifically? Muslim inequalities, inequalities that became ?state-enforced? in the lives of Muslim women.

Next, I return to Nesar Ahmed?s words??marriages mean kolma-kabin??to examine the institutional and ideological processes that are at work to secure these meanings. In that section, amongst other things, I also look into how diverging trajectories of legal and political development has borne different consequences for women, as the case of Bangladesh and Pakistan post-1971 illustrates. As Asad informs us, the modern state (in our case, a ?modernising? one) encroaches into areas of social life that were previously unregulated. In the case of Pakistan, state encroachment, and thereby its power?in the form of legislation?has brought into effect a particular variant of Islamic interpretation of sexuality and marriage (as enacted in the Hudood Ordinance 1979), to regulate the lives of Muslim women in Pakistan, with the application of ?brute force?.

?Singular? meanings: marriage as kolma-kabin

?Kolma? and ?kabin?, as used by Nesar Ahmed, seem to me to be deeply embedded in two different binary oppositions. The notion of a ?kolma marriage? indirectly draws on progressivist debates on religion vs. secularism. A ?kabin marriage? (short for kabinnama) signals government prescribed forms for registering marriages as opposed to the marriage agreement drawn up in Naxal marriages, one drawn up by party officials, that the women had referred to as ?the form?. The kabinnama can be looked at as an instrument of marriage; a part of the administrative and bureaucratic procedure which enforces religious belonging, and corresponding practices, among Muslims in Bangladesh.

Let me add a few more words about the kolma aspect of a marriage: Since marriage in Islam is a purely civil contract, and no specific religious rites are necessary for the contraction of a valid marriage, the verses that the moulobi, or kazi (Marriage Registrar), or any man well-versed in religious norms and practices, chooses to recite from the Qur?an are left to his discretion (usually Fatiha and Durud). Now, on to the kabinnama (variously referred to as the ?marriage document?, or the ?marriage contract?). Generally speaking, it means the Marriage Registration Form prescribed under The Muslim Marriages and Divorces (Registration) Act 1974, which provides for the licensing of nikah (marriage) registrars. Registering the marriage can either take place on the occasion of marriage itself, or the married couple, accompanied by their family members, can later go to the Kazi Office to get it registered. The kazi?s task is to maintain the registers of marriages and divorces, and provide an attested copy of the entry to the parties. An earlier act, the Muslim Family Law Ordinance, 1961 had made registration mandatory; in case of violation, the Marriage Registrar could be liable to punishment through a prison sentence and/or a fine.

Failure to register, however, does not invalidate the marriage. As a High Court judgement states, ?registration is not essential in order to prove the validity of the marriage, and nor is a written kabinnama [essential], if the marriage is otherwise valid? (Bangladesh High Court, March 3, 1998). ?Otherwise valid? would imply that there should be an offer and an acceptance of marriage, the document should be signed by both parties to the marriage in the presence of two witnesses, the groom should not be less than 21 years, and the bride should not be less than 18 years.

Registration may not be essential to prove the validity of a marriage but in cases of dispute, non-registration can, and does, create a host of problems since women have no ?proof? of marriage, essential to asserting their lesser rights within marriage, and to divorce, guardianship, custody of children and inheritance. Hence, women?s organisations and/or NGOs which provide legal support to increasing numbers of women, distraught at either being deserted by their husbands, or at his having taken on a second wife, or not providing maintenance within marriage, etc have demanded, in the interest of ensuring further protection of women?s rights within marriage, that the system of registration be strengthened, that it be made compulsory for all citizens. Its legislation is an important part of the Uniform Family Code (UFC), drafted by the Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, the largest women?s organisation, with the assistance of Ain O Shalish Kendra, which provides legal help, dispute resolution service, and counselling to women in need. The UFC is aimed at protecting the rights of Bangladeshi women of all religions?in matters related to marriage, divorce, custody, alimony, and the inheritance of property?and is said to ?fully comply with the provisions of CEDAW? (UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. The passage of the UFC has been twice stalemated, once in 2005, when the Law Commission appointed by the government to review the proposal stated that Muslim laws are based on ?the Qur?an as a revealed Book,? that its acceptance would lead to the Muslims of Bangladesh rising ?in revolt as one man [sic].? And again this year, when a section of Muslim clerics and some Islamic parties protested against the Women?s Development Policy (of which UFC is a part), on the grounds that the proposed reforms ?violate the Sharia law on inheritance.?

Generally speaking, marriage registration is on the rise. It is now a norm among the urban middle class. It also seems to be rising in rural areas, as a recent study of six villages reports: the marriages of eighty per cent of women below 25 years of age were registered, in contrast to only forty-two per cent registration of older marriages, women aged 45 and more. (Lisa M Bates, Farzana Islam et al, 2004).

But the administrative apparatuses of modernising states are not as efficiently regulatory as are those of older Western states, susceptible as the former are to corruption, to the misuse of public power for private gain. In Bangladesh, instances do exist of Marriage Registrars leaving a couple of pages blank in their register books, only to sell later at a ?high price?, to someone in urgent need of a ?backdated? marriage. As happened in the case of ex-President HM Ershad. Bidisha, his later wife, now-divorced, writes in her autobiography of how a Keraniganj kazi had been able to rustle up such a blank page since Ershad had been concerned to ?prove? to the nation at large that their son, was born in, and not out of wedlock. Ershad, she adds, had constantly grumbled about the exorbitant amount that the blank page had cost (2008).

?Marriages mean kolma-kabin,? and I return to these words of Nesar Ahmed now. Naxal marriages were regulated and controlled by the party, they were shaped by underground living and revolutionary ideals, but not, in contrast to dominant practices of marriage, enforced through administrative and bureaucratic procedures of the state. Marrying, for Naxal women, I contend on the basis of their oral life histories, was a political act. What does marriage mean for the middle class in general, and more particularly for its self-consciously thinking sections? I explore this question drawing on my own personal history, and on critical theoretical literature that I have discussed above. I hasten to add, my ideas are provisional.

Bengali Muslim middle-class marriage, to draw on what I had said earlier, cannot be separated from its class history. Both consciously and unconsciously, members of this class draw on means of ?othering? to mark their own practices as distinct: a polygamous marriage is its ?other? (viewed as essentially Muslim), the flexibility inherent in subaltern practices is its ?other? (kono thik-thikana nai). Now the interesting thing is that although polygamy is legally permissible (albeit subject to restrictions under MFLO 1961), it is not so for the middle class, either in terms of ideology or as a normal practice. Polygamy and other inequalities towards women that are a feature of Muslim Personal Laws in Bangladesh are anathema to the self-consciously thinking sections of society. This, I think, is partly expressed in the struggle for the UFC, which proposes to ban polygamy, declare it illegal, and a punishable offence (a polygamous marriage will not be registered). It also finds expression, I think, in the slogan that emerged in protest against the constitutional amendment of the Ershad government that made Islam Bangladesh?s state religion (1988): ?jar dhormo tar kacche, rashtrer ki bolar acche?? (to each his/her own religion, why should the state dictate?). Although the sections that had united under this slogan at processions and rallies had been small, the underlying notions of freedom and privacy that it upholds has a much broader appeal among large sections of the middle class. I now turn to my personal history, but before doing that let me brush up my question further, the one that I seek answers to: how is compliance secured to unequal laws among the self-consciously thinking sections of society?

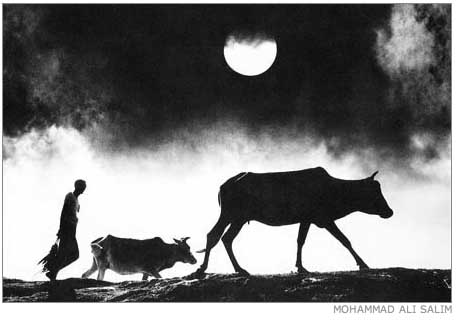

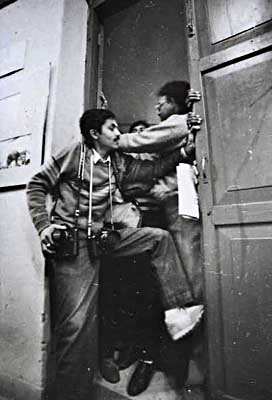

In 1988, Shahidul Alam and I decided to share our lives, but I could not reconcile myself to getting married under a set of laws that discriminated against me as a woman. It was the inequality in the marriage laws?divorce, rights over children, inheritance, the issue of den mohor, ?why should I take mohorana from Shahidul?? ?why could he have four wives and I only one husband at a time???that angered me. Shahidul too, was troubled at the prospect of being invested with greater powers (over me) through becoming my husband, powers that were unequal and legally enforceable. I debated options. I remember that a close friend, a feminist herself, advised me to go abroad and get married. I refused. ?But that is out of the question, we are Bangladeshis.? I remember her reply, ?But why are you so worried anyway? I am sure Shahidul will not exercise his powers as a husband. I am sure you have nothing to worry about, he is not that kind of a man.? I remember that I was silent, that I did not retort, ?But how do I know? How can I know? And if I do find out, won?t it be too late?? I have no doubt that her advice was offered in all sincerity, as one expects from close friends. A simple answer would be to brush it off as an ?elitist? response, but I want to probe deeper. (How Shahidul and I eventually resolved ?our? dilemma is another story. I will not enter into that. No, not now).

Over these last twenty years, as I have observed intelligent and thinking people, whether belonging to the left or the women?s movement, and/or progressivists and secularists, get married under an undeniably unequal set of laws, I have mulled over her words, and wondered: how is a willing compliance to the laws of marriage ensured, particularly among a class of people who consider their ?others? to be religious and superstitious, leading un-progressive lives, lives that are ?dictated? by social norms, forever lagging behind in the task of re-constructing themselves as modern citizens. How is it linked to property rights? Is it reducible to property rights? Or, do we need to pose a different set of questions? I insist that I raise these questions motivated by no other desire but to understand the politics of marriage.

In his more recent writings, Asad has spoken of how ?beliefs? have become detached from social practices, of how they have become ?a purely inner, private state of mind, a particular state of mind detached from everyday practices.? (1996). He has also spoken of secular modern ideas of freedom, of ?the illusion of an uncoerced interiority? (2007). Is that where I should be seeking answers to my question? Is marriage now purely personal and private? Is that why struggles over marriage?for the liberal sections of society?take place in the arena of legal reforms (lobbying, applying pressure politics), and not in a contesting terrain of social practice, of politics?

In another sense, middle-class marital practices (strict monogamy is proposed for all, irrespective of religious differences, in the UFO) can be looked at as being similar to Naxal imaginings of its own practices, of being ?fore-runners to marriages of the future? (Ismat ara Rita?s words). Of course, I must add the caveat that progressivist approaches call on a greater extension of the modernising state?s regulative powers (but then, communist states are no different), aided by international conventions, to initiate ?legal reforms from above.? It is interesting to note that the collective self-descriptions of both middle class (?civilising force?) and Naxal marital practices (?advanced-modern era?) subscribe to ?singular?, Westernising meanings. But similar Westernising meanings may be ascribed to other marriages ?at the margins.? As a High Court judgement states: ?Nowadays the obnoxious culture of ?living together? has made its inroad into our society and this is slowly spreading its tentacles undermining our social values and the institution of marriage.? (1999). And of course, here, ?our? social values, and ?our? institution of marriage is assumed to be genuinely, culturally authentic, untainted by the obnoxious influences of other cultures.

?Processes of Islamisation? that were instituted in colonial times through legal techniques of ruling can, and have been, further exacerbated by the modernising state?s increasing encroachment into social life. Pakistan is such a case, where the state?s law-enforcing agencies and its judicial system, in combination with social forces, have employed ?brute force? against the nation?s Muslim women, targeting those who are, as often happens, less-privileged. The drafting and passage of the Hudood Ordinance (The Offence of Zina (Enforcement of Hudood) Ordinance, VII of 1979) was accomplished by General Ziaul Huq?s regime, a strong military ally of the US government. Coupled with the Law of Evidence, it was put into practice in a manner that blurred distinctions between ?adultery? and ?rape?. The effects of the application of the Ordinance, as has been repeatedly highlighted by women?s organisations of Pakistan, have been horrendous for women. Norms and boundaries of permissible sexuality and marriage, policed as they were by religious forces, were empowered by particular interpretations of Islamic notions that were legally sanctioned by the state.

In the case of Bangladesh, in the last decade or more, similar attempts to enforce sexual norms and boundaries permissible in Islam have occurred. Conducted by social actors at the village level, these assaults have been led by religious forces, at times, in a vigilante-like fashion. In all recorded cases, either only women were punished, or they were punished more than the men who were involved in the incidents. One such woman was Dulali.

Dulali, age twenty-five, became pregnant during an extramarital relationship with Botu, another resident of her village. On discovering her condition, her family arranged her marriage to another man. Her husband, on confirming his suspicions that she was pregnant, however, divorced her. Dulali?s family then reportedly called upon local elders to hold a shalish in the matter. At the shalish, Dulali was accused of zina and sentenced to be caned 101 times, to be administered seven days after the delivery of her child. No accusation was made against Botu, the man involved. (Sajeda Amin and Sara Hossain, WLUML Publications, 1996).

The authors add, national women?s organisations intervened and the presence of the police on the day Dulali was to be punished, acted as a deterrent. Later, the villagers denied that the incident of shalish and the pronouncement of fatwa had taken place. Although not punished for the alleged sexual improprieties, Dulali was no longer able to live in the village. In recent years, accusations of zina (adultery/fornication), sentencing them to punishment such as stoning, caning, and, in a particularly horrifying case, burning at the stake, has led to the death of three women. These acts of policing, I would like to stress the point, have been carried out by social forces, (thus far) they have been sporadic and intermittent. Further, these acts were not acts based on notions legally sanctioned by the state, since zina, under Bangladeshi law, is not a criminal offence.

The modern state: policing intimate relations

The modern state polices the realm of ?the intimate.? Large expanses of social life in modern industrial societies, whether capitalist or communist, are governed by a minutiae of legislative and administrative rules that define and redefine the daily conditions in which subjects live.

Western and bourgeois conceptions of morality?specific to Western history?are inscribed in the law. Asad provides us with an instance: Western normative ideas about childhood are that ?sexual excitation? is dangerous to it, that sexuality is proper only to ?adults?. The Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, an Act that was the outcome of a successful moral campaign to control prostitution, raised the legal age of consent for girls to sixteen. It enabled the police to gain greater powers of jurisdiction over poor working women and children. Although ideas about children?s sexuality have changed since the late nineteenth century, contemporary British society is marked with a concern to protect children against sexuality. State apparatuses, its functionaries and various professionals (paediatricians, psychiatrists, social workers, police, lawyers, probation officers) are employed to constantly police relations between children and adults. Consequently, these relations, says Asad, become charged with a sexual significance since they are objects of suspicion.

Colonial legal reforms were ?imposed upon the people from above,? they enacted Western social practices and Western morals. It was only after the passage of the Criminal Law Amendment Act that child marriage became an object of moral reform in colonial India. Attempts to abolish child marriage were prompted less by what was said, i.e. to protect young girls from being sexually exploited by older men (after all, a man in his fifties can marry an eighteen year old), than to forbid it in cases where both the boy and the girl are similar in age, let?s say, both are twelve years old. Another instance of Western meanings being inscribed in conformity with Western social practices is provided by reforms of Shari?a rules of marriage. A Muslim man?s right to have four wives simultaneously has been restricted (first wife?s permission is required). In other words, reforms have been conducted which restrict the traditional rights of Muslim men, but not, let?s say, enhance the traditional rights of Muslim women. Thus, no legal reform has enabled Muslim women to contract a polyandrous marriage, i.e. have more than one husband simultaneously.

As I write this section on the policing of intimate relations by the modern state, I am reminded of how these policing powers extend to post-independent Bangladesh. My British friend?s Bangladeshi boyfriend had applied for a fianc? visa to go to Britain, to join her. To convince the immigration officials he had to take their personal letters over to the British High Commission in Dhaka, which were carefully scrutinised for indications of ?authentic? love, to determine whether a visa should be issued.

I am also reminded of how legal concepts that are different to Western marriage practices and its own legal history can, and do, encounter institutional arrogance and resistance in the West. For instance, the Muslim marriage contract?kabinnama in Bangladesh, and nikahnama in Pakistan?has been generally treated by the British system (courts, and authorities, such as immigration and pensions) as a ?pre-nuptial agreement?, a concept that is alien to Muslim law. Is a pre-nuptial agreement legally enforceable, can it be the basis for gaining pension benefits? I am led to believe from researches conducted there that this question has not yet been resolved by the British legal system. As a result, Bangladeshi and Pakistani spouses of British Muslims have suffered, and continue to do so. It has also created grounds for litigation between the parties (Recognizing the Unrecognized, WLUML, 2006).

?What is done in reality?

In concluding, I return to Gramsci, to words that he wrote while imprisoned.

Possibility, he said, is not reality: but it is in itself a reality. ?Whether a man [sic] can or cannot do a thing has its importance in evaluating what is done in reality. Possibility means ?freedom.? …the existence of objective conditions, of possibilities or of freedom is not yet enough: it is necessary to ?know? them, and know how to use them. And to want to use them.?

As I said earlier, I have no answers. ?Answers? as such, can only be the outcome of social and political struggles. And, as the Italian Marxist thinker reminds us, the existence of ?objective conditions? is not enough. One has to know of possibilities, one has to want to use them.

But, there is a price to be paid for waging struggles for freedom in the realm of ?the intimate?, for they challenge a hegemonic moral order, one that is universalising in its reach.

—————————————————————

Originally published in The New Age on Monday the 22nd September 2008.

![]()