By Rahnuma Ahmed

The title of my column is somewhat misleading, I think it’s best to state that right away. Intrigued by the press briefings that RAB (Rapid Action Battalion) offices hold every so often where `criminals’ are displayed alongwith crime artefacts laid out on long rows of tables?guns, machettes, grenade-making equipment, stolen cash?as evidence of their criminality, images which are served up on the news of all private TV channels, which are printed a day later in the newspapers, I had thought of conducting research on these photo op sessions. I had wanted to examine these as `sites’ that are organised and arranged by the organs of the state, by the functionaries of the state, ones that construct criminality through visual means, i.e., still photos and video recordings of criminals, their tools, the loot. RAB, for the few who may not know, falls under the jurisdiction of the ministry of home affairs, its members are seconded to the battalion from the army, navy, air force and police, a measure which, according to its critics, eases in the carry-over of its culture of gross abuses and impunity to other parts of the security forces.

RAB Photo Session

RAB Photo Session

My interest in RAB and its activities, as many of my readers probably know, is not new. It re-surfaced recently, however, because of several incidents which gave rise to thoughts, ones that not only refused to go away but dug deep into the soil and grew shoots.

It surfaced as I poured water over a waterproof camera that Shahidul Alam, my partner, held underneath. He was working on re-creating images of water-boarding for his upcoming photo exhibition on torture. I concentrated on carrying out his instructions, on not thinking about how I would have felt if an actual head had been in the bucket. It surfaced languidly as I heard Nurul? Kabir ask third year students of photography?he is currently teaching a course on Media and Politics at Pathshala?to reflect on how the Bangladeshi media participates in non-violent means of ruling. On how it seeks and gains people’s consent to ideas which work against their interests. Drawing instances from how the media had significantly contributed to making Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia, women with no political experience, into `national’ leaders, on how intellectuals, writers and journalists gratuitously offer the view that the nation’s problems would be solved if only the two women would meet and talk to each other, Kabir moved on to a discussion of ideological state apparatuses (the ISA’s, as those familiar with the French Marxist theorist Louis Althusser’s ideas, know). While listening to him, I thought of RAB’s crossfire deaths and how it had simultaneously constructed, and cashed in on an idea of meting out instant justice in a situation of deteriorating law-and-order and a failing criminal justice system, a situation for which the government, of course, was ultimately responsible. I then thought of how it was increasingly becoming difficult for crossfire deaths to garner public support, even of people who supported the government on all other counts. But what about RAB’s press briefings? What did they construct, and what did we consume by watching images of these on television, or through seeing printed pictures?

Mug shots, or photographic portraits of arrested people, taken by police photographers at the police station is not something that is practised in Bangladesh. The genre of photography and framing that has developed since RAB (inaugurated in March 2004) began its press briefings seems unique to Bangladesh, and to its visual history. Through my network of photographer friends I got hold of about sixty photographs, and sat looking through these, scribbling notes while I did: RAB officials conducting security searches on buses. Squad dogs snarling at each other. A pair of startled eyes of a young man, the alleged criminal, in front of whom lay a table full of machettes. He seemed to have been hauled up and planted in front of the table. Three young men, guarded on either side by two RAB officials, but although they seemed to be in the middle of a forest, strangely enough, they had A-4 sheets with their names, computer-composed and printed, hanging on their shirt fronts.

I then turned to dozens of photographs of press briefing sessions. These invariably, with one or two slight variations, had `criminals’ standing behind a long table, covered with a white table cloth, a banner behind announcing the number of the battalion (twelve in all), the alleged criminal or criminals guarded by armed RAB members on either side, criminal artefacts in front. The names of those caught, `Mohd Rafiqul Islam, illegal woman trafficker,’ a meticulous description of what was recovered, `125 bhori gold ornaments,’ `ten thousand US dollars,’ often neatly affixed. To the person. To the object. Reminiscent of colonial inventories.

I spoke to a photographer who has covered nearly a hundred RAB events in the last 4 years. He spoke to me on condition of anonymity. So what happens, I asked. Well, the press, from the channels, from the dailies, we all go at the appointed time. We go to a large room, a hall room. There are chairs for us. It takes about half an hour, the criminals are brought, we are briefed on the crime, what happened, who was caught, with what. We take photographs. I prodded and he said, well, what the RAB official says, and what the alleged criminal says seem to be based on the same script. Does anything ever untoward happen? Have you seen any such thing happen? Oh no, he replied. It’s all very neat, very well-organised. No ruffles, none whatsoever. So, why do they do it? Why do they go to the trouble? I think because they get free publicity. I wondered to myself whether it had made crime reporters and investigative journalists lazy. So, you mean, it’s a package? Yes, his eyes lit up. It’s all pre-packaged, you get everything all at once. Sometimes, he said, I think, it is arranged to divert attention. Whose? Well, the media’s, and thereby that of the public. For instance? If you remember the whole Yaba thing, when it blew up, most of those who were paraded before us were Yaba addicts, there was such a big circus over it but none of the really big fish were caught. So, what makes you think it’s stage-managed? Well, two things. If we see something happening on the street, and RAB is there, in action, and we go up to take photographs, they behave very badly. They’ll snarl and say, `Do you have any permission?’ They beat up a Jugantor photographer once. But then the next thing you know, they’ll organise this elaborate press briefing at their offices and parade these so-called criminals with ten-or-so Phensedyl bottles laid out on the table. And they also offer us tea, snacks. We don’t want their nasta, we want to work, I want to take photographs because I think I am accountable to the public. As he spoke I thought to myself, surely, these staged photo ops violate constitutional rights? What does one call them, a sort of media trial, held in what, RAB’s court? Aloud, I asked, what strikes you as most odd about these sessions? Well, when they put on their sunglasses, I mean we are inside the building, inside a room, there’s no sunlight but these guys put on their dark glasses just before we start taking photos.

I return to examining the photographs. There is one set missing, I think. A set that none of us will probably ever get to see. Those that RAB officials are said to have taken of New Age’s crime reporter F Masum after they beat him up outside his house for failing to open the gate with alacrity. According to him, they later dragged him into his bedroom, placed six Phensedyl bottles in his pillow case, stood him beside it. The camera clicked.

First published in New Age on Monday 16th November 2009.

High Court orders government to explain killings.

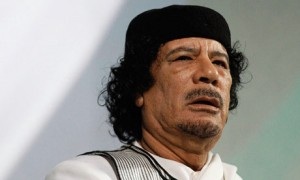

On the dusty reaches out of Sirte, a convoy flees a battlefield. A NATO aircraft fires and strikes the cars. The wounded struggle to escape. Armed trucks, with armed fighters, rush to the scene. They find the injured, and among them is the most significant prize: a bloodied Muammar Qaddafi stumbles, is captured, and then is thrown amongst the fighters. One can imagine their exhilaration. A cell-phone traces the events of the next few minutes. A badly injured Qaddafi is pushed around, thrown on a car, and then the video gets blurry. The next images are of a dead Qaddafi. He has a bullet hole on the side of his head.

On the dusty reaches out of Sirte, a convoy flees a battlefield. A NATO aircraft fires and strikes the cars. The wounded struggle to escape. Armed trucks, with armed fighters, rush to the scene. They find the injured, and among them is the most significant prize: a bloodied Muammar Qaddafi stumbles, is captured, and then is thrown amongst the fighters. One can imagine their exhilaration. A cell-phone traces the events of the next few minutes. A badly injured Qaddafi is pushed around, thrown on a car, and then the video gets blurry. The next images are of a dead Qaddafi. He has a bullet hole on the side of his head.