My first podcast

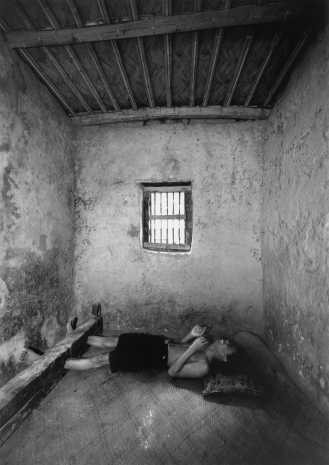

?No one ever comes back,? she said. She was baleful, half a tear welling on her eyes. I had no way of knowing when I might be back. I hugged her tight as she sat on my lap, but my words were not convincing. She had been promised many times before and knew not to be too wishful. The name ?Happy? seemed a difficult one to use to describe her. Yet minutes before Happy Akhter Nodi and I had been playing, laughing, teasing one another. She was probably around 10. She didn?t really know, and I couldn?t really tell.

Her mother had brought her over to the Sonar Bangla Children?s home three years ago. Happy had wanted to come herself. She wanted to study. To become a doctor. To serve people. But parting had been sad. Her mother had come to see her on previous new year days, but this time she?d rung to say she couldn?t make it. There was too much work over the holidays. Happy understood, but it didn?t make it any easier. She wanted to go to the fair, to buy toys, to dress up in a new sari. She wanted her mum. Happy was spunky, bubbly, naughty, and dying to be loved. I tried to tell her that her mother might come another day. We both knew I was pretending.

She was being protective of me. Making sure the other kids didn?t hassle me too much. She became my self appointed muse. The poem by Kazi Nazrul I was trying to sit and translate wasn?t easy and they were all impatient. There was a children?s poem in the book, which she remembered from school, but even that didn?t hold her attention. We both knew I would be leaving soon. The sun was coming down and I was waiting for that sweet light when I would photograph Putul (an older girl in the home) in the green paddy fields. I was there on an assignment, and needed to get back to work. I would then go back to Dhaka, and perhaps out of her life for ever.

?You will ring tomorrow, or I?ll never talk to you again.? This had been the biggest threat we knew as children. ?I?ll never talk to you again.? I nodded, not trusting myself to speak. It would be new year?s day, and it gave me some chance to make amends. She snuggled up to me and said, ?You have to give me a name. One just for us.? Despite her sadness, the name Happy had seemed very apt. She was a happy child. They must have given her the name knowingly. Her mother?s name Adori Begum, had also perhaps been a name she had been given. A woman who provided love. When I?d photographed Happy before, she was being her mischievous self. She?d put on a shawl around her head and looked much older than she was. Now she looked smaller than her age, and very fragile.

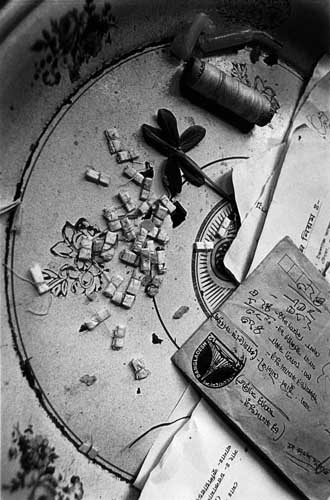

As the light went down, we went to the paddy fields together, holding hands all the way. Happy jealously warding off the other kids. The light was beautiful and Putul glowed in the green paddy. Then it was time to go. As we walked back she guided me through the bracken, protecting me from every thorn. As we came to a clearing, she looked me over and untangled a rubber band dangling from my pouch. It was a worn band, left over from an old baggage tag at some airport. ?I?ll keep this,? she said. ?Now, give me my name.? I whispered back ?Anmona?. It was all I could think of. This wistful girl, with the bright eyes, full of sadness, suddenly seemed so far away.

We said our goodbyes and as all the children rushed to hug and kiss and wave goodbye, Happy stayed back. Silently she repeated the word ?Anmona?. As the car moved out of the gate I could see her through the dust. She was holding on to a worn ragged baggage tag.

1st Baishakh 1414

Bangla New Year’s Day

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh,

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh,