??

Economist

Nov 25th 2011, 13:04 by L.M.

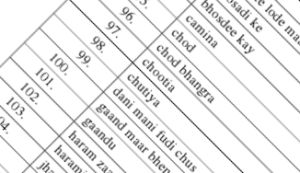

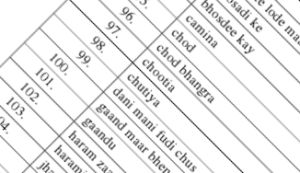

AN OFTEN overlooked perk of being a country with a large population and relatively low wages is the capacity to employ people to carry out silly tasks. In India, for example, some people spend their days pasting white stickers onto maps of Kashmir printed in foreign publications (such as?The Economist). In neighbouring Pakistan, the regulatory body for telecommunications dreamed up an equally unlikely, if altogether more entertaining, assignment for its staff: to compile a list of ?undesired words? that could be used to block offensive text messages. In a remarkable show of efficiency (to say nothing of creativity), the agency managed to find?1,100 words and phrases in English and nearly?600 in Urdu. (Admittedly they may have padded it out a bit?how else to explain the presence of ?robber?, ?oui? or ?k mart? in a list that otherwise places rather more emphasis on sexual adventurism?)

Last week, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority?s (PTA) memo and accompanying list of the words sent to mobile-phone service providers were leaked on the internet. Pakistanis were aghast and amused in equal measure. Previous bans have?targeted Facebook,?Rolling Stone magazine?s website and the use of encrypted networks. These met with limited opposition. But the directive to block text messages containing certain words was seen as an attack on free speech.

The official reason for the ban was ?to control the menace of spam in the society?. Far more likely, the authorities finally grew tired of rude anti-government jokes that circulate widely via text message. Many feature the president, Asif Ali Zardari, in a starring role. (A tame example: ?The post office issued new stamps with Zardari?s face on them but they had to be withdrawn because the public found them too confusing: it was impossible to tell which side to spit on.?) Texting is perhaps the most effective means of mass communication in Pakistan: two of every three Pakistanis have a mobile phone and the cost of sending an SMS is among the cheapest in the world. Following public uproar, damning editorials and the threat of legal action from NGOs, the authority sheepishly announced that ?implementation of previous PTA instructions have been withheld? after it ?received input from customers, government and other quarters on this issue?.

The government?s inability to take a joke isn?t restricted to text messages. In an interview with the state broadcaster on November 21st, the UN?s ?world television day?, the information minister, Firdous Ashiq Awan, stressed the need for a code of conduct to help broadcast media through an ?evolutionary phase?. There is little doubt that Pakistan?s news channels could do with some restraint, especially when it comes to coverage of terrorist attacks, which tends towards the gory. But critics fear that an enforced code of conduct would use obscenity as an excuse to target the hugely popular political satire programmes that make fun of the nation?s ruling classes. ?It?s anti-government stuff, impersonations of Zardari and company?they don?t leave anyone alone. They make all kinds of jokes, some of them quite lewd,? said Murtaza Razvi, a senior editor at?Dawn, a leading English-language newspaper.

Pakistan?s broadcasting rules were liberalised under Pervez Musharraf soon after he took power in a military coup in 1999, and the number of television channels quickly grew from a single state broadcaster to nearly a hundred channels. The government would do well to draw a lesson from the experience of Mr Musharraf, who tried to clamp down on press freedom in 2007 and found himself out of office soon after. Mr Zardari may not enjoy being the butt of jokes every night but it certainly beats having angry?protesters on the streets of Islamabad.

Villagers are doing it for themselves

Villagers are doing it for themselves