Razia Haque was incensed. She was not a trendy environmentalist. Her sentences weren?t interspersed with English and she didn?t know any of the developmental jargon. She was a grandmother who lived in Elephant Road who walked through the park everyday to drop off her granddaughter at the university. But she knew this was wrong. ?Nature is for everyone. What do they think they are doing? How many years has it taken for these trees to grow? They?ve destroyed the beauty of this place. They?ve dulled our senses. It can only cause bitterness. About common people, about the government about everyone. They do as they please. How can you allow this? You should all give slogans. Who has authorised the cutting of these trees? Once the trees have gone there?s nothing you can do. Just because they?re in power they?ll cut down the trees, how can that be??

Continue reading “Getting in the way”

Tag: Dhaka

Bangladeshi blogger Abu Sufian wins ?Reporters Without Borders? Category Award in Best of Blogs contest

BANGLADESHI BLOGGER WINS ?REPORTERS WITHOUT BORDERS? CATEGORY AWARDS

Bangladeshi journalist?Abu Sufian?s blog?about extrajudicial executions and other kinds of injustice is the jury choice in the ?Reporters Without Borders? category of this year?s BOBs (Best of Blogs competition), organized by the German radio station Deutsche Welle. It was was chosen from 11 finalists by an international jury consisting of bloggers and a Reporters Without Borders representative. Continue reading “Bangladeshi blogger Abu Sufian wins ?Reporters Without Borders? Category Award in Best of Blogs contest”

Khaled Hasan wins Samdani Arts Award

Magnum Foundation Interview

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Conversation between Shehab Uddin and Shahidul Alam

UDDIN: I’m a freelance photographer in Bangladesh and I first met Shahidul in 1998. At that time I was in my hometown in Khulna. Shahidul, who also moved to Bangladesh a few years earlier was organizing all the photographers here. So it was a great moment for me to meet him.

After that, I came to Dhaka in 1990 and I joined a newspaper here. In 2005 I decided that work in the newspaper was not right for me, and I had the opportunity to join Drik and work directly with Shahidul. So I took the opportunity and worked there as a photographer. It was really a milestone, and a breakthrough for me.

ALAM: The agency [Drik] was set up primarily because we were very concerned that countries like Bangladesh, which some have called “third-world countries” and we choose to call “majority-world countries,” have been portrayed almost invariably through a very narrow lens. It worries me that Bangladesh has become in the eyes of many, an icon of poverty. The reality is something we cannot ignore. Shehab shows it through his work and I have no intention of wallpapering over the problems we have. What I do have a serious problem with is when people are denied their humanity and become icons of poverty; they become lesser human beings.

The agency was set up because we wanted to tell stories that got across the richness and the diversity of people’s lives and we realized the story had to be told by people who had empathy for the subject. So it was a platform for local practitioners. And that’s the birth of Drik. But when we started, we realized that a lot of the photography infrastructure a Western agency has acess to, was not available to us. So we started creating some of that infrastructure here. Later on we also began developing educational structures that could foster new talents. We are one of the few agencies in the world that has two galleries of its own, runs a school of photography, and runs its own photography festival; I do not know of a single other agency in the world that does anything of this type. But all of that is really part and parcel of Drik’s photography-philosophy–in telling rich and diverse stories without compromising the subject’s humanity–we just had to create a whole space for ourselves. And now we are telling our own stories.

Continue reading “Magnum Foundation Interview”

Beyond Walls Outside Frames

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

A photographer is rarely a good editor of one?s own photographs. It?s not as illogical as it sounds. The visual content within the four corners of a frame create the stimulus that inform us of what was seen, and in well crafted images, conjure up the sense of the moment. For the photographer, it is a small part of the process. The pain, the pleasure, the frustrations, the high, of arriving at the photograph, is an inseparable part of the image. The editorial choice therefore, cannot be made on the image alone. The emotional weight impinges upon one?s judgment. It is a valid choice, but one that the viewer unencumbered by that weight, is incapable of sharing, and hence a choice, less relevant to the viewer.

A teacher in selecting work by students goes through a similar process. The path is neither smooth nor predictable. Students with different ability, drive, tenacity and energy occupy a classroom. Work produced by a student one has nurtured over years is difficult to reduce to a set of visual frames. The coaxing, cajoling, willing and hand holding that has gone into each student. The stance one has taken, stern but generous, appreciative but demanding, kind but rigorous, finds its way into each image. Each portfolio has a stamp, invisible to others but clearly present to the teacher. How then does one take a dispassionate view, while selecting work for a collective publication?

Of course there is the chronology that maps out the growth of the organisation. The transitions that have taken place, contoured by collective experiences. The visiting faculties who have left lingering traces upon individual styles. Influences that have sometimes dramatically altered the visual practice. Return to familiar paths. Explorations into the unknown. Blatant copies arising out of adulation. Rejection, rethinking, a process of morphing where the old and the new have combined to produce a new genre altogether, are easy to observe. The branches can be traced to the roots with every knurled knot, every fork, every green shoot a sign of a new beginning.

Then comes the difficult part. When bright sparks of brilliance shine through in defiance. When a body of work refuses to be categorised. When another, just as strong, pulls in a different direction. How does one choose between favourites? How does one forget the angst that led to a new vision? When a student returns from being almost lost, and basks in new-found confidence, can work be excluded, merely because it doesn?t fit? Can brilliance be ignored merely because there are other stories to tell, and there just isn?t enough room?

Other dynamics also enter the equation. Talent and success don?t always go hand in hand. Having taught one?s students survival skills, one must appreciate their ability to get ahead, make the right impressions, learn to play the ?game?. In that game of life, there are those one admires more, for their integrity and honesty. For staying true to their beliefs. For not selling out. That the less scrupulous are sometimes the ones who shine is a reality one needs to accept. Having handed over the tools, one cannot hold back. It is arrogant to assume one?s value systems will be valued by all. In the rough and tumble of survival, many will choose options one might not fully subscribe to. Many will walk paths, one would hope they would avoid. Some will deceive, some will massage the truth. Some will benefit as a result. That too is reality.

When a reject pile is so rich with nuggets how does one lament? What message does it carry when rejection is so value loaded? When rejected work is seen as inferior. When the editors sword can affect careers, change lives. In the binary of inclusion, there is no middle path. No also-rans. Work is in, or out. The pain of losing out is not easily shared.

Hopefully, the book will speak for itself. While regretting what has been lost, one must not fail to rejoice in what is present. Inevitably there are internal references. New work that is informed by former attempts. While other bodies of work have marked the path for future students to follow. Global influences have also pitched in, but generally, it is the peers who have paved the way for future students.

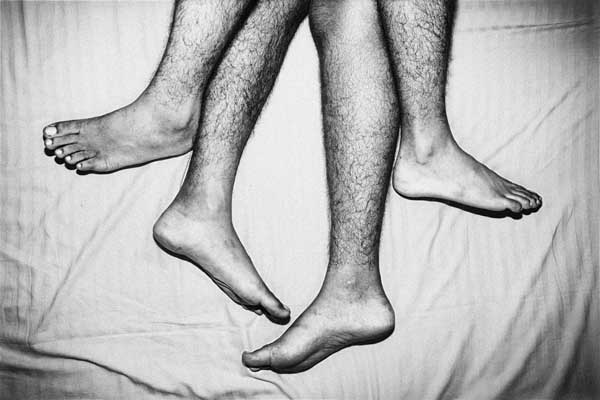

The early work of Abir Abdullah, produced at a time when the genre of photo essays was largely unexplored in Bangladesh, was emulated by others in his own batch like GMB Akash. Akash himself became a trendsetter for future students. The gritty colours of Andrew Biraj and the ethereal black and whites of Munem Wasif took divergent exploratory routes while their classmate Nazrul Islam, found inroads into contemporary life in Kabul. The exquisite image construction of Saiful Huq Omi was perhaps the precursor of the equally accomplished sculptural images of Khaled Hasan. Din Mohaammad Shibly?s exploration of family life might well owe to the tender insight by Munira Morshed Munni into the intimacies of her own home. The stark rendering of the invisible gay community by Gazi Nafiz Ahmed, might have evolved from the very different approach that Akash had taken many years earlier, while Masud Alam Liton stayed closer to the early documentary style. Noor Alam?s insightful look at children with thalassaemia surely gained from the work on children with cancer by Nayemuzzaman Prince.

Choosing from the 8th batch was particularly challenging. While the individual styles of Debashish Shom, Shehab Uddin and Shumon Ahmed have all made it to the book, the ones left out include important work by Chandan Robert Rozario, the strong graphic imagery of K M Asad, the harrowing story by Saikat Majumder and the exquisite well-crafted frames of Khaled Hasan. The distinctive approaches of Tanvir-ul-Hossain and Nurun Nahar Nargish, could have represented the new contemporary movement in Bangladeshi photography. They too got bypassed because more thought provoking work was on offer.

Taslima Akhter brings us face to face with the inequalities of class that fuel our growing economy, but lost were Ashraful Awal Mishuk?s insights into the Bangladeshi underworld. Giving up Syed Asif Mahmud?s dreamy visuals was particularly heart wrenching. The well executed night scenes by Sarker Protick fought its way in, but it was the joy of seeing exciting, vibrant, exploratory work by the young photographers, Arifur Rahman, Rasel Chowdhury, Tushikur Rahman and Jannatul Mawa that got the adrenaline going. They refuse to be hemmed in by the four corners of a frame. They reject the notion of walls. This is Pathshala and Bangladeshi photography shamelessly showing off. Long may it do so.

DHAKA WORLD MUSIC FEST? 2011

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

The end of the international photography exhibition Chobi Mela leads onto a two day Dhaka World Music festival – 4th and 5th February, 2011.

TIME : Friday 4th 3:pm – 11PM

Saturday 5th 3pm-11pm

Sultana Kamal Mohila Krira Complex. Dhanmondi

The first-ever Dhaka World Music Fest? ? February 4 ? 5, 2011, brings the eclectic grooves and hypnotic rhythms of Cuban-funk, Afro-beat, Baul, Reggae, Pala and Bangla-Latin fusion to your ears like never before.

The 2-day musical extravaganza features a plethora of world-class musicians from home and abroad. The month of February is eternal in the heart of each and every Bengali people and celebrating this auspicious month through the Universal language of music goes far beyond our geographic periphery since 21st February is celebrated as ?International Mother Language Day? across the world.

The Dhaka World Music Fest promises to be Dhaka?s official yearly international music hotspot, ushering in its new era as World Music hub. This will be the ultimate international musicfest experience to captivate all music-lovers.

The Bands

Dele Sosimi Band ? legendary Afro beat band from one of the originators of the Nigerian genre

Shahjahan Munshi ? Master musician who brings the blues to baul

Motimba ? fiery Cuban funk

Lalon band ? Bangla folk rock fusion at its best

Rob Fakir ? hypnotic contemporary Baul

The New Leaf

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

?Ah GMG? When to come when to go. Nobody know.? At least the guy had a sense of humour. I?d woken up at a ridiculous hour to get to the airport on time. The flight was scheduled at 6:45 am. Reporting at 4:45. Putting my battered arm in a sling, I had set off in pitch darkness. There were no counters marked GMG at the airport, but asking around they pointed me to row 4.

The monitors showed KU, the code for Kuwait Airways, but there were other passengers waiting for the same flight, so it looked as if I was in the right place despite the empty counter. I was heading to Chennai to train Indian photojournalists in a workshop arranged by the World Association of Newspapers WAN-IFRA. I hadn?t fully recovered from my recent accident, but since the participants were from all over India, and they had also advertised my lecture widely, it would have been awkward for them to change dates. Sadek, my physiotherapist had given me a big list of don?ts. There was no reference to standing at empty airline counters. The Haiku response by the airport official didn?t really help.

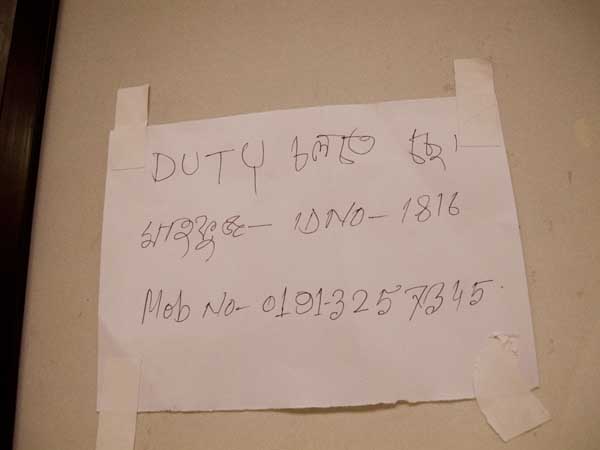

I did have a close connection and thought I would check. ?No general enquiry counter. Not inside the airport,? explained another airport staff. ?Try the GMG office on the 2nd floor.? The 2nd floor office was also closed. A hand written note in Bangla, gave the number of Mosaddek. A man answered, ?I know nothing about the flight, please try the ground staff. Office in other terminal next to the Gulf office on 4th floor.?

The journey continued. A young Indian man, also a passenger, joined me. The GMG office along the way was closed. ?There is one round the corner,? said a man in the corridor. ?That flight?s been closed for 4-5 months? said Mr. Anwar when we finally found a GMG office that was open. Both he and his colleagues were very helpful. ?We?ll endorse your ticket and make sure you get there,? they said. ?We don?t get passengers. There were a few flights during Durga Puja, but otherwise we don?t operate this route. Please get your ticket and we?ll arrange something.? So with my dud arm in sling and my young friend in tow, off I went.

Continue reading “The New Leaf”

A Two Day Visa

They sing in harmony. Rhythmic tunes with simple lyrics. The lilting songs and the dance-like-footsteps have a deceptive beauty. The metal sheets balanced on their shoulders may weigh tons. Bare feet on slippery clay weaving through scrap metal, is dangerous at the best of times. In pouring rain, and with the loads they carry, the smallest slip could spell disaster. They gently sway in careful steps singing to stay in synchrony. It is a song of death.

Online Norwegian version in Dagbladet

shipbreaking-magazinet1?PDF in Norwegian Magasinet

dagbladet-nyhet?PDF in Norwegian Nyhet

“You wouldn’t have the time” he’d said. It was a polite conversation. Salahuddin, the cousin of Jahangir Alam, had rung me to thank me for helping him get an ambulance at the Apollo Hospital in the elite Bashundhara Complex in Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka, 250 kilometres from the port city Chittagong. Despite the hospital’s motto of “Bringing healthcare of international standard within the reach of every individual,” it was understood that all patients were not equal. Jahangir and his family had been waiting for over five hours. The hospital was for rich people and Jahangir, a worker at Ziri Subeder Shipbreaking Yard was undeniably poor. Even though the money had been paid, Jahangir, on his deathbed was not going to get the same treatment the other VIP patients at Apollo were given. Eventually the presence of a pesky journalist taking pictures had enough nuisance value for the hospital to dredge up an ambulance. Jahangir would arrive at a cheaper, less equipped hospital in Chittagong, in the early hours of the morning. Knowing I was interested in the plight of the workers, Salahuddin had rung to tell me there had been another accident. A worker was in hospital and they were going to amputate his leg. He felt my presence might save the man’s leg. I was due to go to London the following day, for a brainstorming meeting with Amnesty International. Going to and from Chittagong that day would have been difficult. I had things to do before leaving. Salahuddin was right. Even though I knew that my presence might perhaps have made a difference to a man’s life. I didn’t have the time. We never have the time. Not for some people.

The working conditions at the shipbreaking yards of Chittagong are well known. It is the usual story. In order to get the ships, the Bangladeshi shipbreakers pay the best rates to the ship-owners. To retain their profits, they pay the workers the lowest rates in the world, and provide virtually no safety. Workers die and suffer injuries on a regular basis. Some receive modest compensation, others don’t. According to workers, many deaths are simply not registered with the bodies being ‘disappeared’ by the owners.

I had wanted to do a story on the shipbreaking yards for some time. When Halldor Hustadnes of the Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet approached me I was immediately interested. I rescheduled a short assignment in Manila so that we could work together for the entire period. A loophole in the Basle Convention was allowing ship-owners to continue dumping ships with toxic waste with abandon in majority world countries that had little regulation.

The new International Maritime Organisation, convention was about to be ratified, but environmentalists felt it would not result in better conditions for workers. Norwegian ship-owners, who benefitted the most from loopholes in the convention (like the ships not being declared waste, and therefore not falling under waste jurisdiction), were a powerful lobby. Even Lloyds the insurers, who register and control the world’s shipping, felt the new convention would not have an effect.

We were hoping our story, timed to appear before the ratification of the convention, would bring attention to the plight of the workers. Getting access to the yard was going to be the main stumbling block. My student Sourav Das, put me in touch with Wahid Adnan. Adnan had good links with Rahman yard. We had been told that the Norwegian ship UMA was berthed at Rahmania yard. The slightly different name might just have been due to a mistake in communication. There was a ship UMA near Rahman yard. This was a breakthrough. Adnan managed to get me in, but though it was the right ship, it was the wrong yard. UMA was going to be broken at Royal, the yard next to Rahman, where we had no access.

So we started with the access we had, and worked our way across the porous beach. It was a Friday. The weekend in Bangladesh. We utilised the absence of the manager to bluff our way into the ship. The abundance of asbestos, the open chemical store, the sacks of Potassium Hydroxide pellets and other toxic chemicals left unprotected, were all fairly visible. One of the workers talked of the films they had been shown about how asbestos was toxic, and had to be buried under concrete and that workers needed to wear protective clothing. “But that was just a film” he said.

Shujon was the smallest of the workers. With marigolds dangling from his ears, he insisted on being photographed. He behaved like a child, though we found out he was older than he looked. Only wealthy Bangladeshis have birth records. And with most children being malnourished, looks can be deceptive. Shujon was a helper. Hirolal, the cutter he was helping, didn’t look much older than him. They were cousins. Shielding his eyes from the intense heat with his hands, Hirolal, broke down larger pieces of metal into more manageable shapes. Shujon cleared the debris, oblivious to the sparks that flew around him. Both boys wanted to find work overseas. Singapore was their dream destination. I didn’t tell them that Bangladeshi workers in Singapore, often found themselves in similar bonded labour. At least Shujon and Hirolal had a dream. The contractor came over and started beating up Shujon. He needed to get on with his work. We were getting him into trouble and kept our distance.

Early the following morning I saw Rubel, bailing out the water from a lifeboat. Rubel was 14 and had been a ferry ‘man’ since he was 11. His mother didn’t really want him to be doing risky work, but they needed the money. We left before sunrise, before the manager arrived. Rubel was well into his day’s work.

That night when the manager had left, we went back into the yard and slept with the workers. We were guests and had the luxury of having a metal sheet to ourselves for a bed. They sung for us that night. Not the pop songs that we heard on television, or the Tagore songs that the wealthy elite took as a sign of culture. They were haunting songs of longing and parting. One was a song about visas:

With a two day visa

To this false world

Why did Alla send me

Why send me here

With the pain of seeking comfort

He sent me on my own

What game did he play

What game does he play

- Using metal sheets for beds, workers sleep in crowded huts with no toilets. 11th August 2008. Chittagong. Bangladesh ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MW/Dagbladet

With an empty water bottle and a wooden box as a drum, we sang into the night. Their raw voices blending with the steady rain on the tin roof. “We are poor folk. There’s work tomorrow. We need to sleep.” The foreman said abruptly. We knew the songs had been sung for the entertainment of the guests, at the cost of much needed rest. I walked out into the rain. The tide was coming in. UMA was glistening in the yard searchlight. The guards in their yellow raincoats stood out in the darkness.

Captain Inam was a boisterous jovial man. He was the most experienced beach captain, and the de-facto spokesperson for the shipyard owners. He was much in demand. When we wanted to speak to the owners, they insisted that the good captain be around. The owners spoke little, leaving it up to the articulate seaman to fend our questions. They invited us over to Bonanza, a posh restaurant in downtown Chittagong. One of the many businesses owned by Mr. Amin, in whose yard two other Norwegian ships, the Gold Berge and New Berge were also being stripped. Captain Inam explained how the ship-owners who made the bulk of the profit took no responsibility for the situation of the workers. How they should allocate a percentage of their profits to building a modern shipyard in Chittagong. How these environmentalists were in collusion with the Northern ship-owners and working towards increasing their profits. Of how the shipyard owners really felt for the workers. Of how they provided helmets, and gloves and shoes to all workers, but that workers didn’t want to wear them. None of this matched with what the workers had to say. “A pair of shoes cost us 500 Taka” they said. That was four days’ wages for the average worker. Odfjell the Norwegian owner of UMA had made 7.5 million dollars from the sale of the dying ship.

The foreman cutter talked of how he had escaped death but the person next to him had died due to poisoned gas in the hull of a ship. He took us to his one room house where the parents and the two children shared a bed that almost occupied the entire room. He talked of the four times they had tried to set up a union. Each time the local goons were used to beat them into submission. The main organisers were tortured and lost their jobs. Captain Inam, has a different version. “There are no restrictions to forming unions.” He says. “The workers are simple people and don’t think in those terms.”

The number of injuries have gone down enormously says the captain. Now there are hardly one or two a year. They take us to the hospital they are building, to reduce medical fees paid to external hospitals. We never went into the logic of requiring to build a hospital to reduce costs if only one or two deaths and a few injuries were taking place all year.

One of the workers Saiful takes us to a nearby village. Walking a few hundred metres, we come across several families of injured workers. A few say they have received modest compensation. Some say they’ve received nothing. Even though these injuries were from a few years ago, the frequency of injuries has little in common with the captain’s figures.

Shahin, an NGO worker who has been campaigning for the rights of shipyard workers, rings us to tell us of an accident that has just taken place. We rush over to Chittagong Medical Hospital (CMH). As all other public hospitals in Bangladesh, CMH is overrun. The three workers were carried up the five flights of stairs and lay on the hospital floor. There were no spare beds. Jahangir was the most badly injured. His head was bleeding, and he couldn’t move. He was barely conscious. The other two workers had broken limbs but would survive. There were no stretchers and Jahangir’s family and friends, took him across to a less busy part of the hospital floor, carrying him on a stretched sheet.

We contact Al Hajj Lokman Hakim, the owner of Ziri Subedar Yard. Mr. Hakim is angry. “They have accidents because of their own stupidity. Sometimes they have minor injuries, and we have to pay for it. If these foreigners care so much about our workers why don’t they build a new dock for us?” Cursing everyone in sight as we go down the lift of his highrise building, the Lokman Tower, Mr. Hakim drives off in his shiny car. A 5.5 million Taka car according to our driver.

The news was more than Jahangir’s mother Nurjahan could take. Her eldest son had an accident a year ago. Two months ago her husband had died. Two weeks later, Alamgir, Jahangir’s younger brother had been injured while working in a different yard. The yard owner had paid for Alamgir’s treatment, but there was no knowing if he would ever be able to work again, or how long the owner would keep paying for the treatment. Jahangir had been the only earning member of the family. As it was, the family depended upon the generosity of the neighbours for their survival. Jahangir’s injury had left the family in tatters. “It is poverty that has driven my sons to this life,” says Nurjahan. “If my Jahangir returns, I will never send him to the yard again.”

Jahangir never returned. On the night of the 6th September, Jahangir had spoken. He seemed to be on the verge of recovery. He would never walk again, but at least he would live. The following morning Shahjahan heard he had died. Shahjahan knew that the company had been concerned about the rising medical bills, and wondered if Jahangir’s death had been necessary to keep the bills down. One thing was certain. His two day visa had expired.

The ship owners in Norway, will never know he lived.