Subscribe to ShahidulNews

| Subject: Thinking of you Sent: 02/13 3:21 AM Received: 02/13 5:09 AM From: shahidul@drik.net To: Pedro Meyer, pedrom@directnet.com Dear Pedro,  I have not written to you for a long time now. Things have been difficult here, and now with the elections only three days away, it is difficult to know what the next few days will bring. It is fairly certain there will be violence, but to what extent and with how many casualties, one can only guess. I have not written to you for a long time now. Things have been difficult here, and now with the elections only three days away, it is difficult to know what the next few days will bring. It is fairly certain there will be violence, but to what extent and with how many casualties, one can only guess.I have been remembering you for very different reasons. For three days now my father has been ill. He has always been poorly, and with diabetes, gout, arthritis, and a failing heart, adding to his childhood bone marrow defects, he feels he has done well to keep going without any major mishaps. Yesterday, he had a blackout and slipped in the bathroom and fell, cutting himself on the head in the process. He was sweating when I found him, and as I changed his clothes and mopped his body with a towel, I found a new relationship developing between myself and this man who had fathered me. He was frail, and his skin hung loose, and he was slightly uneasy with this new role that we found each other in, but he did not resist, not because he was as weak as he was, but because he was brave enough to venture into this unknown territory at this late an age. A territory, I had never braved. I tried to gently mop the sweat from his body, feeling him lean on me, letting me feel his weight. I had played with him as a child, but since then, we had had little scope for physical contact. I remember once, when I was twenty one, and about to leave for several years, that he stiffly held out his hand to shake mine. I went up to him, and his hug was so warm. Later, from a thousand miles away, I wrote to him to say that I loved him. It was the first time I had done so, but we had broken the ice. We wrote often since then, each time renewing and expressing our knowledge that we loved each other, but there had still been little to follow up on that hug. When I left for a visit, or returned, we would hug, a soft gentle hug, knowing, trusting, but still holding back ever so slightly. |

|

|

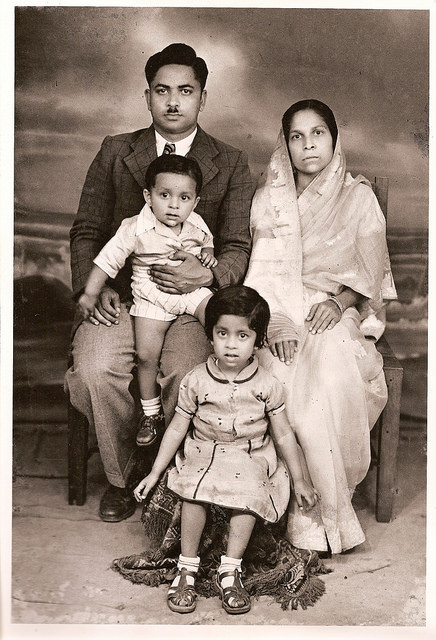

| Subject: My father Sent: 02/20 11:30 AM Received: 02/20 12:35 PM From: Shahidul Alam, shahidul@drik.net To: pedro meyer, pedrom@directnet.com Dear Pedro, The text is a bit formal. It will take me a while to write to people individually. I hope you will understand. RENOWNED BANGLADESHI SCIENTIST PASSES AWAY Professor Kazi Abul Monsur, a microbiologist of international repute, passed away on the 20th February 1996 at Suhrawardy Hospital of a heart attack. A brilliant scientist, Professor Monsur was a gold medallist from Calcutta Medical College, and was later awarded the “Pride of Performance” by the President of Pakistan. He developed the world’s best known culture media for cholera, known as “Monsur’s Media”. He was the founder of the School of Tropical Medicine, and also the initiator of the first IV fluid plant in Bangladesh. His work brought international recognition and he served as the director of the Public Health Institute. Professor Monsur started his teaching career in Dhaka Medical College where he was professor of Bacteriology and Pathology, which was followed by many years of international work. He retired from Government service as Director of Health Services. Dr Monsur has left behind his wife, Dr Anwara Monsur, founder and principal of Agrani Balika Bidyalaya, daughter Dr Najma Karim, son Dr Shahidul Alam, grandchildren, and many well wishers. Dr Monsur was a director of Drik Picture Library Ltd. |