By Rahnuma Ahmed

I see no reason not to be worried.

For we have, over the years, begun mimicking our erstwhile Pakistani rulers when it comes to explaining what went wrong in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

The `tribals’ want to secede. They want to breakup the nation. The loyalty of the `tribals’ has always been suspect, in 1947, they didn’t want to join Pakistan, they had wanted to be part of India. The Shanti Bahini was aided and abetted by anti-Bangladesh forces outside. It is an Indian conspiracy to destabilise the country. Agreeing to the `tribal’ demand for autonomy diminishes the sovereignty of the Bangladesh state.

And what had our Pakistani rulers said, both before, and during, 1971?

The Bengalis want to secede. It’s an Indian conspiracy. Our mortal enemy India, wants to break up Pakistan. These Bengalis began agitating from the word go, first they wanted their own language, 1949, 1952, and then, from 60s onwards, they began demanding regional autonomy. Those in the Mukti Bahini are India’s paid agents. The Bengali Muslims are Hindus, anyway. They listen to Rabindra sangeet, the women wear saris, they put teep on their forehead. Agreeing to the Bengali demand for autonomy will be a threat to the sovereignty of the state of Pakistan.

There are other reasons to be worried, too.

There are some similarities in the responses of both sets of rulers: a militaristic response. In the case of ekattur (our liberation war), this was accompanied by Lieutenant General Tikka Khan’s declaration, `I want the land, not its people.’ Tikka was the architect of Operation Searchlight, launched on the night of 25th March 1971. We will always remember him as the Butcher of Bengal. A military commander, deluded into thinking that his efforts would save the nation.

The Awami League government had initiated and eventually signed a peace treaty with the PCJSS (Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti) in 1997. A few weeks after the signing of the Treaty, Khaleda Zia, as leader of the opposition, had declared: it will lead to the setting up of a parallel government. Others said, it was signed to please the Indian government. Writ petitions have been filed since, challenging the validity of the Peace Treaty. During a recent court hearing, the petitioners listed some of the reasons: the former chief whip of Parliament had no authority to sign the Treaty. He was not authorised by the President. A treaty can only be signed between two governments, the CHT people are not only not a government (!), they are “controlled by an Indian intelligence agency.” They are not indigenous to the land, “they” are settlers etc., etc. (New Age, 17 March 2010).

As things stand, some may think that the Awami League, by virtue of having initiated and signed the Peace Treaty, want peace in the hills, while the BNP (and its bed-fellow, the Jamaat), doesn’t want peace in the hills. There may be some truth in it.

But there’s more truth in what Bhumitra Chakma, a Jumma academic who teaches politics at the university of Hull, says: the recent attacks, on 19 and 20 February 2010, carried out by Bengali settlers in Baghaichari, backed by the armed forces prove yet again that unless the Bangladesh state addresses the structural roots of violence, the “cycle of violence” will continue (Economic and Political Weekly, 20 March 2010).

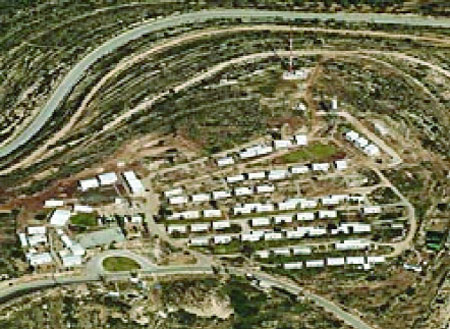

“At the core of the problem,” writes Chakma, is the Bangladesh government?s “politically-motivated Bengali settlement policy” aimed at changing the “demographic character of the CHT, which inevitably leads to clashes over land.”

The Bengali settlement policy, in my mind, was diabolical. By selecting “landless” Bengalis, it seemed that the military government was concerned about the futures of those who are poor, it helped hide the fact that their landlessness and abject poverty made them more amenable to military direction and control; that, as far as the military leadership was concerned, they were civilian subalterns/canon fodder. The settlement policy whipped up populist sentiments in the rest of Bangladesh: `If someone from the CHT can settle in Rangpur, if he can buy land there, why can’t someone from Rangpur go and live and work in the CHT? It’s one country, after all.’

The settlement policy seeped into public discourse, it helped re-define Bengali nationalism on territorial lines?as all nationalism is, is bound to be?but the new sense of territory/ nationalism was not of the resisting kind, of the kind that grows out of an urge for self-defense (like 1971), but one which encroached.

I am persuaded that this newly developing form of nationalism was distinct to the nationalism of the Mujib era (1972-1975). When Sheikh Mujib had exhorted the indigenous peoples “to forget their ethnic identities,” to merge with “Bengali nationalism,” what lay behind his words was a heady cultural arrogance, deeply entwined with feelings of racial superiority.

Bengali nationalism as encroaching, in a territorial sense, one which could be implemented through the planned deployment of coercive power, came later. After 1975.

I am inclined to think that it was at this historical moment that we i.e., the Bengalis as a nation?began to sound like our erstwhile rulers.

The latter, according to us, were colonisers.

Colonial orientation to land, and its people

One of the greatest liberal philosophers John Locke, analysed English colonialism in America in terms of his theory of man and society. I present Locke’s arguments below, based on a discussion by Bhikhu Parekh (The Decolonization of Imagination, 1995).

Locke had argued that since the American Indians roamed freely over the land and did not enclose it, since they used it as one would use a common land, but without any property in it, it was not `their’ land. That the land was free, empty, vacant, wild. It could be taken over without their consent. The Indians of course knew which land was theirs and which was their neighbours, but this was not acceptable to Locke who only recognised the European sense of enclosure.

However, there were native Indians living by the coastline, who did enclose their land. English settlers were covetous of these lands, they wanted these lands for themselves as it would help them avoid the hard labour of clearing the land. They argued that the native Indian practice of letting the soil regenerate its fertility, to let the compost rot for three years, meant that the natives did not make “rational use” of it. Locke agreed with them. Even enclosed land, he said, if it lay without being gathered, was to be “looked on as Waste, and might be the Possession of any other.”

Some Indians, however, not only enclosed the land, they also cultivated it. But they were still considered guilty of wasting the land because they produced not even one-hundredth of what the English could produce. The trouble with Indians was, according to Locke, they had “very few desires,” they were “easily contented.” Since the English could exploit the land better, “they had a much better claim to the land.” It was the duty and the right of the English to replace the natives, and, as long as the principle of equality was adhered to, no native should starve, nor should she or he be denied their share of the earth’s proceeds, English colonisation was infinitely more preferable. It increased the inconveniences of life. It lowered prices. It created employment.

The culture of indigenous peoples the world over, as has been noted by many political theorists, is inextricable from their culture. Take away their land, and you take away their culture.

Land in the Chittagong Hill Tracts belongs to the paharis. It is their land. A refusal to understand this means opening us to the allegation of whether our nationalism is their colonisation.

Bhumitra Chakma speaks of the “cycle of violence.” It is a cycle that is embedded in larger cycles. Nationalism. Colonialism.

My Bengali sense of freedom surely cannot be paid for by the blood of others?

A genuine leap of the national imagination

George Manuel, Secwepemc chief from the interior of British Columbia (Canada), indigenous activist and political visionary whose work on behalf of indigenous peoples spans the globe, writes:

When we come to a new fork in an old road we continue to follow the route with which we are familiar, even though wholly different, even better avenues might open up before us. The failure to heed (the) plea for a new approach to ..[Bengali-pahari] relations is a failure of imagination. The greatest barrier to recognition of aboriginal rights does not lie with the courts, the law, or even the present administration. Such recognition necessitates the re-evaluation of assumptions, both about [Bangladesh] and its history and about [Jumma] people and our culture-?Real recognition of our presence and humanity would require a genuine reconsideration of so many people?s role in [Bangladeshi] society that it would amount to a genuine leap of imagination. (Cited by Paulette Regan, Canada, 20 January 2005, by making the replacements in square brackets I have taken a liberty for which I hope I’ll be forgiven).

Are Bengalis capable of making a genuine leap of imagination? However hard, however difficult, we must. For the sake of the nation. For the sake of ekattur.

First published in New Age 26th March 2010