Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Rahnuma Ahmed

“A lion is stronger than a man, but it does not enable him to dominate the human race. You have neglected the duty you owe to yourselves and you have lost your natural rights by shutting your eyes to your own interests….”

— Begum Rokeya, Sultana’s Dream (1908)

New York, 1906

Clara Lemlich, a young Jewish woman, joined a group of shirtwaist makers. They wanted to form a union, but didn’t know how. Six young women, six young men and Clara formed Local 25. In those days, the ILGWU (International Ladies Garment Workers Union) was small. Most of its members were male cloakmakers.

Although Clara was determined to be a “good girl,” two days later she was talking union. The oppressive conditions at work made her angry. The forewoman would follow the girls to the toilet. She would needle them to hurry. New girls would be cheated, their pay was always less than agreed upon. The girls would be fined for all sorts of things. They were charged for electricity, needles, and thread. “Mistakes” would be made in pay envelopes, they were difficult to get fixed. The clock was fixed so that lunch hour was twenty minutes short. Or, it would be set back an hour. Not knowing, they would work the extra hour. Unpaid (Meredith Tax, “The Uprising of the Thirty Thousand”).

Clara took part in her first strike in 1907. At one of the union meetings, strikers argued about “pure-and-simple-trade-unionism.” Clara asked one of them what that meant. They went for a walk. Her first lesson in Marxism took place during that forty block long walk. “He started with a bottle of milk?how it was made, who made the money from it at every stage of its production. Not only did the boss take the profits, he said, but not a drop of milk did you drink unless he allowed you to. It was funny, you know, because I’d been saying things like that to the girls before. But now I understood it better and I began to use it more often?only with shirtwaists.” (Paula Scheier, “Clara Lemlich Shavelson”).

In 1908, the first Women’s Day was initiated by socialist women in the United States. Large demonstrations were held.

In 1909, a Women’s Day rally was held in Manhattan. It was attended by two thousand people. The same year, women garment workers staged a general strike. Known as the Uprising of the Thirty Thousand (or Twenty Thousand, depending on the source), the shirtwaist makers struck for thirteen weeks. The weeks were cold and wintry. They demanded better pay, better working conditions.

Bangladesh, 2008

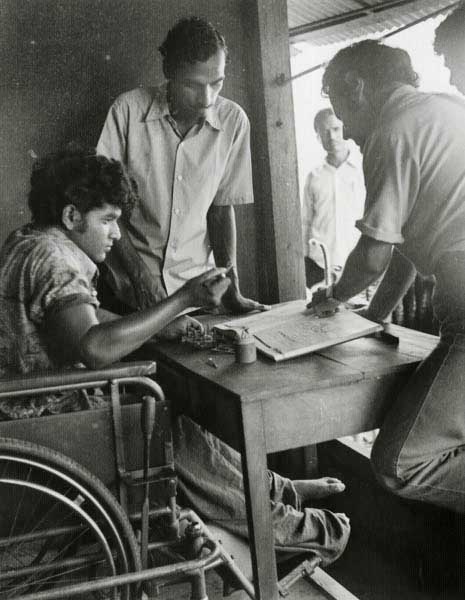

Things are better now, says Moshrefa Mishu, president of the Garments Sromik Oikko Forum (Shomaj Chetona, 1 January 2008). Of course, there are still problems. Workers wages are not paid within the first week of the month. Overtime payments are irregular. Festival allowances and festival leave is not forthcoming unless the girls take to the streets. The minimum wage (1,662.50 taka ?USD 24) is not paid. There is no earned leave. No weekly holidays. Girls do not get maternity leave. If they become pregnant, they get sacked. Appointment letters are not issued. No identity cards are given. They do not get government holidays . For unknown reasons, the eight hour work day, the result of the 1876 May Day movement, and other international movements organised by workers, is not followed in the garment factories. Safety standards in most factories, many of them located in residential areas as opposed to industrial ones, are horribly lacking. These factories, says Mishu, are “death traps.” These traps have killed five hundred workers. Electric short-circuits have led to fires, workers fleeing to save their lives have been trampled to death, locked exits have remained locked even during accidents, or poorly-built buildings have collapsed burying workers underneath the rubble. Mishu spoke of the collapsed Spectrum garment building in Savar, of factory workers in Tejgaon, and of KPS factory workers in Chittagong.

Things are a bit better now, says Mishu, who has been organising workers, and fighting for their rights for the last thirteen years. It was far worse in the beginning. Girls would be worked to their bones. They would work the whole night, but would not get their night bills. Nor would they be paid their overtime bills. Often, not even their basic salaries. There would be a lot of dilly-dallying over wages, aj na kal, this would go on for 2-3-4-5 months. And then, one fine morning the girls would come and and find that the owners had packed up and left. In the middle of the night. No wages, no overtime, nothing in exchange for many months of hard labour. Having a trade union to protect their rights was unheard of. Not only was there no maternity leave, if a girl’s pregnancy was `discovered,’ she would immediately lose her job. She would be forced to leave, penniless. Physical assaults, beatings, threats of acid attack, other forms of intimidation were common. Owners do not regard workers as their colleagues or co-workers, but as slaves. As their servants However, Mishu adds, things have changed. Not big changes. Tiny ones. (Sromik Awaz, 12 January 2008).

She goes on, I have seen many marriages break up. The factories had this outrageous attendance card system. It said, work hours are from 7 am to 5 pm. But, in practice, women worked till midnight. Or, till one in the morning. Why or how it is allowed to happen, I do not know, said Mishu. The 1965 law, the Factory Law says women workers work hours can only be from 7 in the morning to 8 at night. How that can be so blissfully violated in the case of garment factory workers, I do not know. Of course I understand, if there is a shipment yes, but surely there aren’t shipments the whole year round.

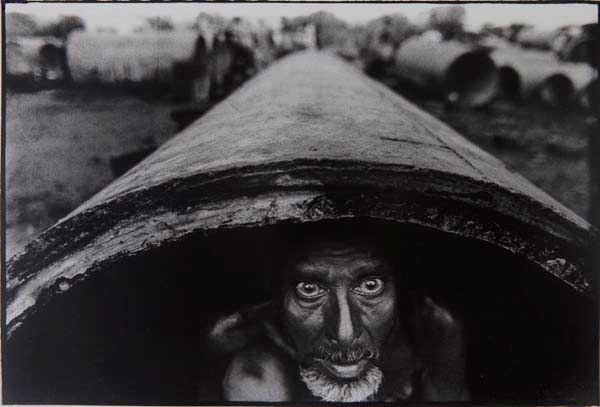

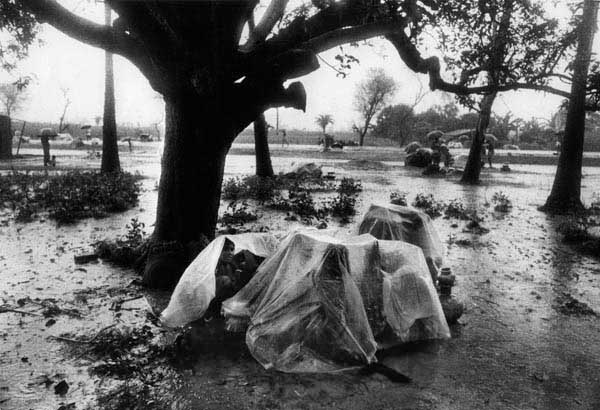

Yes, I was talking about work hours, said Mishu, when girls returned home late, of course, they would be returning from work but since the attendance card said work hours were from 7 to 5, husbands would be suspicious. I know of husbands who would beat their wives, who would drag her by the hair, yell abuses, “Where have you been, you whore?” And also, in our country, it is not safe for women to be out so late at night. Rapes, gang rapes, these happen. They still do. Inside the factory too, there is a lot of sexual harassment. There are other problems, there are no colonies close to the factories where the girls can live. They come to Dhaka city in search of work, leaving behind their families in villages, in townships. They live here in a mess, many to a room, or they take in a sub-let room. They can pay the rent, or the local shopkeeper for food items, rice, salt, oil, on getting their wages. If they can’t pay, they are harassed by the landlord, or by the shopkeeper. I know of girls who have been turned out of their rooms by the landlord, sometimes in the middle of the night. Because they could not pay their rent. I have seen girls in Adabor (Mohammodpur), I have seen them take refuge in front of Shaymoli cinema hall, in the verandas of local mosques, and yes, even beneath a tree. And, as you know, girls working in garment factories are very young, as young as 16. The oldest girls are in their early to mid-twenties.

Mishu said, the Emergency has affected the garment workers movement adversely. The May 2006 movement arose over piece rate payments. Payments were very low at the Apex factory. Workers protested, the police opened fire. Shohag, a young worker, was killed. The movement spread like wildfire, in Gazipur and beyond. It spread to Savar, to Ashulia. It erupted later again, in October. We achieved some, said Mishu, our demand for minimum wages, for setting up of a wage board. We also lost. The wage board would include representatives from both owners and workers. But both sets of representatives were to be selected by the owners! Eleven organisations had demanded a minimum wage of three thousand taka. But we were betrayed. Minimum wage was fixed at 1,162.50. But even that is not paid. Of course, we haven’t given up our demand for a minimum wage of three thousand taka. It is ridiculous to expect that workers can live, they can reproduce their labour power, at such low income levels.

The Emergency has adversely affected the garment workers movement. It has made things much worse. Before, because of one movement after the other, there was some hope. The factory owners had nearly agreed to trade unions. I don’t know what the ILO (International Labour Organisation) office is doing sitting here in Dhaka, I am sure they know that trade union activities are banned. That workers do not have basic democratic rights. As a result of the Emergency, we cannot put any pressure on the owners to follow the 2006 tripartite agreement. We cannot pressurise the government either. The owners are benefiting from the Emergency. They are sacking workers, they are implicating both workers and leaders in false cases. There are 19 such false cases against me in Gazipur, and 7 in Ashulia. Working people are increasingly getting very angry. Spontaneous movements keep bursting out in different factories. Whenever any protest takes place, you get to hear another round of conspiracy theories. Either the workers are conspiring. Or their leaders are conspiring. Or, it is an international conspiracy. Issues of social justice in the sector that owns three-quarters of the nation’s foreign exchange earnings, are sidelined.

As far as garment workers are concerned, this government is no different from other governments, said Mishu. It looks upon us as the enemy, as conspirators. It instructs the police to fire bullets at us. Things far worse happen to us. The Emergency has taken away our rights. It has increased the power of the owners over the workers. Our movement is part of the larger movement for democracy, not the state-sponsored one, but the people’s one. The real one. And of course, we wish to link up to other movements that oppress people.

Postscript: A hundred years ago, Sultana had a dream. The lion is bigger and stronger than a man. Just like men who are [generally] bigger and stronger than women. One can invent similar parallels. Like factory owners, who are richer than workers, and have state backing unlike workers. Other parallels also come to mind.

But in Sultana’s Dream there is a twist. Those who are stronger, and more powerful eventually lose. They are outwitted by their captives, who dreamt of freedom and emancipation.

First published in New Age 8th March 2008