Chakma’s in the Chittagong Hill Tracts celebrate Biju, at the end of Chaitra, just before the traditional Bangla New Year, the beginning of Baishakh. The Marma’s follow the Burmese tradition and celebrate a few days later. Happy 1420.

Continue reading “Shubho Biju, Shubho Nobo Borsho, Happy Bangla New Year 1420”

Tag: Bangla

Ten Photos, Ten Stories: Munem Wasif on GMB Akash

by Naeem Mohaiemen

Ten Photographs, Ten Stories[Translated from Bengali by Naeem Mohaiemen]

By then, the inevitable happened. First Shahidul, then Shehzad, Abir, Kiron? one after another, a daring piece of work. All hard core black-and-white, capturing a humane moment. Akash also started out in this mode. There was a unique caring in his photographs. A forgetful rider on an exhausted horse at the beach. Or, an intimate scene of Akash’s mother bathing his grandfather. These early black and white photographs carry the shadows of that established style. In any case, there was tremendous pressure on the younger photographers. Difficult to stand with your head held high. Not easy to brush off the weight of that established structure. If there is no new language, new stories cannot be told. Then even breathing became difficult. Continue reading “Ten Photos, Ten Stories: Munem Wasif on GMB Akash”

Kakababu choley gelen: Sunil Gangopadhyay (1934-2012)

by Udayan Chattopadhyay

That the passing of Sunil Gangopadhyay came as a shock to many ? despite his age and health ? is a reflection of his being, till his last Puja season during which he died ? the most prolific and recognizable mainstream writer in post-1947 Indian Bengal. Continue reading “Kakababu choley gelen: Sunil Gangopadhyay (1934-2012)”

Job Offer in Deutsche Welle, Germany

Deutsche Welle is looking for a senior journalist primarily for two years to lead the Bengali Department situated in Bonn , Germany .

Qualification:

University degree on any subject

Some years of experience of working in Radio, TV and Online Media

Ready to live and work in Bonn , Germany

Knowledge on politics, economics, history and culture of Bangladesh , India , Germany and Europe

Good command over German and English language

Apply with a cover letter mentioning the Job Announcement Number 040/12, CV and a

Photo within 08.08.2012 to Ms Gabriele Hein, Head of the Human Resource Department of Deutsche Welle, Bonn .

Send the application to this email

Munem Wasif on Prothom Alo

????? ??????? ???? ???? ?????

?????? ?????? |??????: ??-??-????

????????? ????????????? ?????? ???? ???? ???? ??-??????? ????????????? ??? ??? ??? ???? ????? ????? ???? ?????? ??????? ????? ???????????? ?????????? ??????? ??-????? ?? ??-??????? ???????????? ???????????? ???????? ??-???? ????? ????? ??? ????? ???????? ????? ?????? ?????????? ?????? ???? ????????????? ??? ????? ????? ???? ?? ????? ????????? ????? ???? ?????????? ????? ????????? ??-??????? ????????? ????? ??? ???? ???? ????

??? ??? ???? ???? ??? ????? ????? ?? ???? ???? ????? ?????? ?????? ??? ???? ????????? ????-??????, ????? ??-????????? ????? ?????? ????? ??? ?? ?????????? ???????? ????? ??????? ?????? ????? ???????? ???????????? ???? ??-???? ?????, ??????????? ???????? ?? ????? ???? ????? ????? ?????, ??? ????? ????? ??-?????? ?????? ?????? ??-?? ????? ???? ???? ???? ?????, ??????????? ??? ????????????? ????? ????? ??? ?? ?????? ?? ??-??????? ?????? ???? ???? ?????????? ???? ?????? ??-????? ????????? ??????? ?? ???? ?? ??-????? ????? ????? ??-????????? ?????? ??????? ???? ????? ??????? ??? ????? ???? ??????

??-????? ???? ?????? ?????? ???????????? ???? ??????? ??????????? ?????? ?? ???? ????? ??? ?????? ????????? ??????? ???? ????? ?????? ??? ??? ??? ?????? ?????? ??? ????????? ????? ????? ????? ???? ???? ????? ??????? ????? ????? ?????? ????-?????? ????? ?????? ?????????? ?????? ????????? ???????? ???????? ????? ??????? ????????? ????????? ?????? ???? ??????? ??? ????????? ???????? ????-?????? ???????????? ?????????? ????????? ??? ?????? ??????? ??????? ????? ???????? ??????????? ????????? ???? ????? ?? ???? ???? ???? ??? ???? ????? ???????? ???????? ????????, ????? ?????? ?????? ?????? ?????? ????? ???? ????, ???? ????? ??????? ???? ????? ???? ???? ????? ??????? ????? ??? ???? ????????, ??? ????????? ????? ????? ???????? ?????? ???-??????? ????, ???? ?????????? ?????? ??????? ??? ? ?????????? ??????? ??? ????? ???? ?????? ???? ??? ???????? ????-???????? ??? ???? ????? ??? ??????? ??? ???? ???? ?????? ???? ???? ????????? ????? ???? ????????? ?????? ????? ???? ???? ????? ??????? ??? ????? ???????? ???? ????? Continue reading “Munem Wasif on Prothom Alo”

The BOBs – Deutsche Welle Blog Awards

The BOBs – Deutsche Welle Blog Awards.

The BOBs begin on February 13

That time of year has come around again. Starting on February 13, we?ll be looking for your suggestions for the eighth annual Deutsche Welle International Blog Awards ? better known as the BOBs.

Like last year, we?re getting ready to accept your favorite sites in 11 languages. We understand: Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, English, French, German, Indonesia, Persian, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish.

This year we?re also happy to announce that the BOBs site is back at full strength and available in all 11 of the competition?s languages ? in fact, we?re putting the finishing touches on the site right now!

While there are some changes in store for 2012, including a couple of new faces on the jury panel (more about them soon), the BOBs will still feature a Jury Awards as well as User Prizes. The combination of online voting and jury-selected winners makes sure the BOBs continues to honor the best blogs, websites and campaigns on the Internet without turning into a popularity contest.

This year our jury of media experts, activists and bloggers will meet up in Berlin in May to debate and decide who takes home top honors in the BOBs. Patricia Cammarata, better known as das Nuf, joins the panel for German and Steve Vosloo comes on-board for the English-speaking world. We?ll be giving you a more intimate introduction to Patricia and Steve, as well as the rest of the jury members, in just a few days time. Continue reading “The BOBs – Deutsche Welle Blog Awards”

Songs of a Wounded Image

(Editor’s introduction to “Birth Pangs of a Nation” produced to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the birth of Bangladesh and the 60 anniversary of the establishment of UNHCR.)

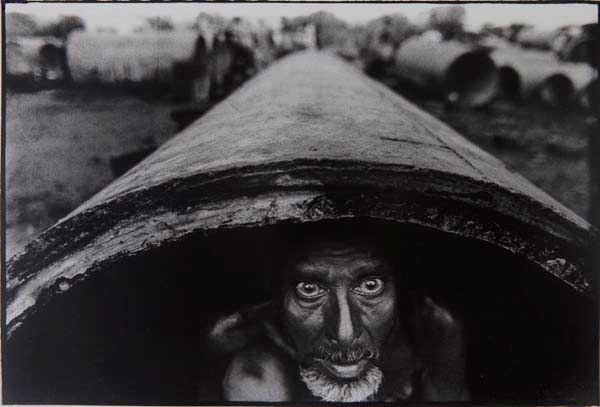

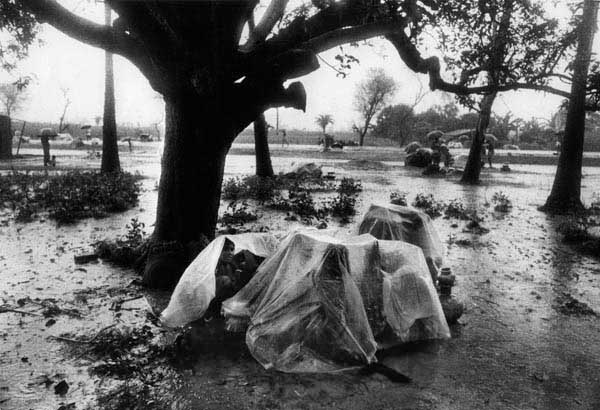

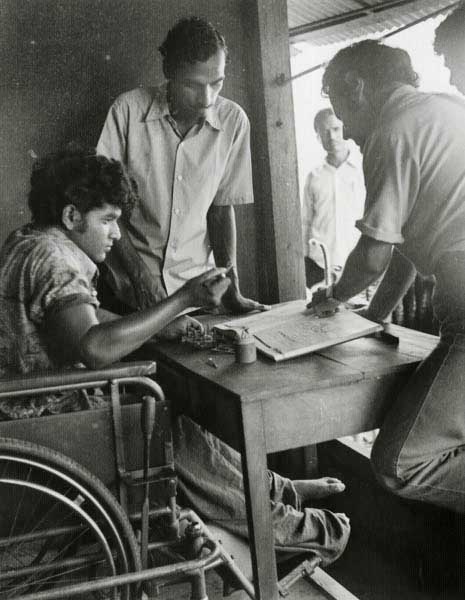

The Bangladeshi War of Liberation, like all other wars, has a contested history. The number killed, the number raped, the number displaced, are all figures that change depending upon who tells the story.

But in our attempt to be on the ?right side? of history, we often forget those who ended up on the wrong side. Those who have gone, those who were permanently scarred, mentally, physically, socially, don?t really care about our statistics. The eyes that stare into empty space, knowing not what they are searching, the frail legs, numbed by fatigue, drained by exhaustion, yet willed on by desperation, the wrinkled hands, seeking a familiar touch, a momentary shelter, longing for rest, do not care about the realpolitik of posturing superpowers.

Is a 40th anniversary more than a convenient round number in a never-ending cycle of the displacement of the weak? Is a 60th anniversary more than a celebration of a milestone amongst many, where brave men and women have stood by those in need, but watched in silence as the perpetrators of injustice continued in their violent ways, leaving them to deal with the fallout?

Continue reading “Songs of a Wounded Image”

she had a dream…

Rahnuma Ahmed

“A lion is stronger than a man, but it does not enable him to dominate the human race. You have neglected the duty you owe to yourselves and you have lost your natural rights by shutting your eyes to your own interests….”

— Begum Rokeya, Sultana’s Dream (1908)

New York, 1906

Clara Lemlich, a young Jewish woman, joined a group of shirtwaist makers. They wanted to form a union, but didn’t know how. Six young women, six young men and Clara formed Local 25. In those days, the ILGWU (International Ladies Garment Workers Union) was small. Most of its members were male cloakmakers.

Although Clara was determined to be a “good girl,” two days later she was talking union. The oppressive conditions at work made her angry. The forewoman would follow the girls to the toilet. She would needle them to hurry. New girls would be cheated, their pay was always less than agreed upon. The girls would be fined for all sorts of things. They were charged for electricity, needles, and thread. “Mistakes” would be made in pay envelopes, they were difficult to get fixed. The clock was fixed so that lunch hour was twenty minutes short. Or, it would be set back an hour. Not knowing, they would work the extra hour. Unpaid (Meredith Tax, “The Uprising of the Thirty Thousand”).

Clara took part in her first strike in 1907. At one of the union meetings, strikers argued about “pure-and-simple-trade-unionism.” Clara asked one of them what that meant. They went for a walk. Her first lesson in Marxism took place during that forty block long walk. “He started with a bottle of milk?how it was made, who made the money from it at every stage of its production. Not only did the boss take the profits, he said, but not a drop of milk did you drink unless he allowed you to. It was funny, you know, because I’d been saying things like that to the girls before. But now I understood it better and I began to use it more often?only with shirtwaists.” (Paula Scheier, “Clara Lemlich Shavelson”).

In 1908, the first Women’s Day was initiated by socialist women in the United States. Large demonstrations were held.

In 1909, a Women’s Day rally was held in Manhattan. It was attended by two thousand people. The same year, women garment workers staged a general strike. Known as the Uprising of the Thirty Thousand (or Twenty Thousand, depending on the source), the shirtwaist makers struck for thirteen weeks. The weeks were cold and wintry. They demanded better pay, better working conditions.

Bangladesh, 2008

Things are better now, says Moshrefa Mishu, president of the Garments Sromik Oikko Forum (Shomaj Chetona, 1 January 2008). Of course, there are still problems. Workers wages are not paid within the first week of the month. Overtime payments are irregular. Festival allowances and festival leave is not forthcoming unless the girls take to the streets. The minimum wage (1,662.50 taka ?USD 24) is not paid. There is no earned leave. No weekly holidays. Girls do not get maternity leave. If they become pregnant, they get sacked. Appointment letters are not issued. No identity cards are given. They do not get government holidays . For unknown reasons, the eight hour work day, the result of the 1876 May Day movement, and other international movements organised by workers, is not followed in the garment factories. Safety standards in most factories, many of them located in residential areas as opposed to industrial ones, are horribly lacking. These factories, says Mishu, are “death traps.” These traps have killed five hundred workers. Electric short-circuits have led to fires, workers fleeing to save their lives have been trampled to death, locked exits have remained locked even during accidents, or poorly-built buildings have collapsed burying workers underneath the rubble. Mishu spoke of the collapsed Spectrum garment building in Savar, of factory workers in Tejgaon, and of KPS factory workers in Chittagong.

Things are a bit better now, says Mishu, who has been organising workers, and fighting for their rights for the last thirteen years. It was far worse in the beginning. Girls would be worked to their bones. They would work the whole night, but would not get their night bills. Nor would they be paid their overtime bills. Often, not even their basic salaries. There would be a lot of dilly-dallying over wages, aj na kal, this would go on for 2-3-4-5 months. And then, one fine morning the girls would come and and find that the owners had packed up and left. In the middle of the night. No wages, no overtime, nothing in exchange for many months of hard labour. Having a trade union to protect their rights was unheard of. Not only was there no maternity leave, if a girl’s pregnancy was `discovered,’ she would immediately lose her job. She would be forced to leave, penniless. Physical assaults, beatings, threats of acid attack, other forms of intimidation were common. Owners do not regard workers as their colleagues or co-workers, but as slaves. As their servants However, Mishu adds, things have changed. Not big changes. Tiny ones. (Sromik Awaz, 12 January 2008).

She goes on, I have seen many marriages break up. The factories had this outrageous attendance card system. It said, work hours are from 7 am to 5 pm. But, in practice, women worked till midnight. Or, till one in the morning. Why or how it is allowed to happen, I do not know, said Mishu. The 1965 law, the Factory Law says women workers work hours can only be from 7 in the morning to 8 at night. How that can be so blissfully violated in the case of garment factory workers, I do not know. Of course I understand, if there is a shipment yes, but surely there aren’t shipments the whole year round.

Yes, I was talking about work hours, said Mishu, when girls returned home late, of course, they would be returning from work but since the attendance card said work hours were from 7 to 5, husbands would be suspicious. I know of husbands who would beat their wives, who would drag her by the hair, yell abuses, “Where have you been, you whore?” And also, in our country, it is not safe for women to be out so late at night. Rapes, gang rapes, these happen. They still do. Inside the factory too, there is a lot of sexual harassment. There are other problems, there are no colonies close to the factories where the girls can live. They come to Dhaka city in search of work, leaving behind their families in villages, in townships. They live here in a mess, many to a room, or they take in a sub-let room. They can pay the rent, or the local shopkeeper for food items, rice, salt, oil, on getting their wages. If they can’t pay, they are harassed by the landlord, or by the shopkeeper. I know of girls who have been turned out of their rooms by the landlord, sometimes in the middle of the night. Because they could not pay their rent. I have seen girls in Adabor (Mohammodpur), I have seen them take refuge in front of Shaymoli cinema hall, in the verandas of local mosques, and yes, even beneath a tree. And, as you know, girls working in garment factories are very young, as young as 16. The oldest girls are in their early to mid-twenties.

Mishu said, the Emergency has affected the garment workers movement adversely. The May 2006 movement arose over piece rate payments. Payments were very low at the Apex factory. Workers protested, the police opened fire. Shohag, a young worker, was killed. The movement spread like wildfire, in Gazipur and beyond. It spread to Savar, to Ashulia. It erupted later again, in October. We achieved some, said Mishu, our demand for minimum wages, for setting up of a wage board. We also lost. The wage board would include representatives from both owners and workers. But both sets of representatives were to be selected by the owners! Eleven organisations had demanded a minimum wage of three thousand taka. But we were betrayed. Minimum wage was fixed at 1,162.50. But even that is not paid. Of course, we haven’t given up our demand for a minimum wage of three thousand taka. It is ridiculous to expect that workers can live, they can reproduce their labour power, at such low income levels.

The Emergency has adversely affected the garment workers movement. It has made things much worse. Before, because of one movement after the other, there was some hope. The factory owners had nearly agreed to trade unions. I don’t know what the ILO (International Labour Organisation) office is doing sitting here in Dhaka, I am sure they know that trade union activities are banned. That workers do not have basic democratic rights. As a result of the Emergency, we cannot put any pressure on the owners to follow the 2006 tripartite agreement. We cannot pressurise the government either. The owners are benefiting from the Emergency. They are sacking workers, they are implicating both workers and leaders in false cases. There are 19 such false cases against me in Gazipur, and 7 in Ashulia. Working people are increasingly getting very angry. Spontaneous movements keep bursting out in different factories. Whenever any protest takes place, you get to hear another round of conspiracy theories. Either the workers are conspiring. Or their leaders are conspiring. Or, it is an international conspiracy. Issues of social justice in the sector that owns three-quarters of the nation’s foreign exchange earnings, are sidelined.

As far as garment workers are concerned, this government is no different from other governments, said Mishu. It looks upon us as the enemy, as conspirators. It instructs the police to fire bullets at us. Things far worse happen to us. The Emergency has taken away our rights. It has increased the power of the owners over the workers. Our movement is part of the larger movement for democracy, not the state-sponsored one, but the people’s one. The real one. And of course, we wish to link up to other movements that oppress people.

Postscript: A hundred years ago, Sultana had a dream. The lion is bigger and stronger than a man. Just like men who are [generally] bigger and stronger than women. One can invent similar parallels. Like factory owners, who are richer than workers, and have state backing unlike workers. Other parallels also come to mind.

But in Sultana’s Dream there is a twist. Those who are stronger, and more powerful eventually lose. They are outwitted by their captives, who dreamt of freedom and emancipation.

First published in New Age 8th March 2008

The Price of Peace

![]()

I am the rage I am the storm

My path I leave barren and shorn

Swaying in my crazy dance

I rejoice at all I face

Move at my own pace

I grapple my foe

I wrestle to die

I am the warrior, head held high*

He was a dreamer, a rebel, a lover, a poet. He moved strong men to tears and woke a nation to unite against tyranny. The British imprisoned him only to find his pen spewing venom from the prison cell. Yet, Kazi Nazrul Islam was a romantic, and his lilting songs, magical stories and even his fiery verse did more to bring together Muslims and Hindus than any peacemaker had ever done. The poor turned away from God?s door, the lover spurned, the weak, the meek, the downtrodden, all found refuge in his words and his music. Unlike the literary giant of the time – Tagore, Nazrul was uncompromising. He spoke of strife, and the peace of acquiescence was never his mettle. Mixing Persian, English and Hindi with his majestic repertoire in his native language Bangla, Nazrul called a nation to war against its occupiers, but also spoke out against the tyranny of religion and class. It was his haunting love songs however, that made Nazrul inimitable. Living the life he preached, he refused to conform. Marrying outside religion, shunning material comfort, and eventually rejecting our carefully defined sanity, he rebelled against a peace that required the acceptance of the status quo. Conflict was his muse.

Lalon, long before him, had traversed a very different terrain. The journey between the body and the soul. The metaphors of the bird and the cage, with the soul flirting with the body, elusive. tantalizing and ever so ephemeral. The sufi saint dealt with the conflict between the material world and the spiritual realm. But for Bangladeshis it wasn?t Tagore or Lalon or even Nazrul, but the struggle for language itself that galvanized the nation. Separated from India on the basis of religion when the British were forced to leave, East Pakistanis had always felt exploited by the West wing and discontent had been brewing, but it was when Jinnah declared that Urdu would be the national language of Pakistan that people took to the streets. The violent birth of Bangladesh, gave a nation with its own language, but Bangali nationalism too became the oppressor of other cultures and the indigenous people of the Hill Tracts have been brutally reminded ever since that they are the other. Their peace could only be earned at the cost of their identity.

Surendra Lal Dewan, was sad that his song had been stolen by the president, but that was not what pained him most. As director of the Tribal Centre in Rangamati, he was required to bring out Pahari women dressed in ethnic garb at regular intervals. They would dance in bright tribal costumes for tourists, visiting dignitaries and even curious Bangalis whenever the state needed to demonstrate Bangladesh?s tolerance and its ethnic diversity. In his song Dewan had spoken of a Bangladesh free of oppression and torture. That a military general, claiming the song to be his own, would use the same words to chant of an egalitarian Bangladesh pierced Surendra with his own words.

Even the naked halogen lamp that shone on the creaky planks that made up the stage near Ispahani Gate 1 had gone. It was the port town of Chittagong and there was no electricity. It didn?t affect Mustafa Kamal and the UTSA theatre group. A string of candles lit up the actors. The children came up close. Kamal wasn?t involved in national issues. He and his group performed to children and their parents, in the slums around Gate 1, and in many other parts of the country. The plays would talk of HIV/AIDS, dowry and land rights. The team would go out to villages and settle land disputes, or fights over someone?s loss of face, by getting the villagers to enact their strife in public. Their participatory plays used humour, love and the occasional risqu? dialogue to enthrall a rapt audience who found a momentary outlet from their tortured lives. But the plays were not simply about temporary relief. They introduced strategies for dealing with the tensions that built up between the landed and the landless, between the buyer and the seller, but also between friends, relatives and neighours. Kamal understood that conflict was a natural product of relationships. While controversies and grievances resulting from differences in values, competition for resources, or perceived threats, often result in conflict, its mitigation rarely depends entirely upon the solution of the problem, but might only require a release through rituals of protest.

Artificial barriers between nations, illegal occupation of lands, the struggle between the worker and the employer, the exploitation of women and children, and the suppression of minorities generate sparks that might set ablaze communities, and the fires needed to be doused. But there was more to art than being the key to the cage. Kamal worried that while his art might allay the tension, it might, through appeasement – like the empty rhetoric of politicians, like the opium fed to the hungry child, like the comfort assured in afterlife, like the promises of peace by generals – help perpetuate the greater wrong.

Shahidul Alam

Los Angeles

24th May 2007

* Translated and adapted from the poem ?The Rebel? by Kazi Nazrul Islam

Abridged from an essay written for the Prince Claus Fund for the 2007 Award Book on the theme ?Culture and Conflict?.

Kazi Nazrul Islam (b. May 25, 1899 ? d. August 29, 1976 ) was a Bengali poet, musician, revolutionary and philosopher who is best known for pioneering works of Bengali poetry. He is popularly known as the Bidrohi Kobi ? Rebel Poet ? as many of his works showcase an intense rebellion against oppression of humans through slavery, hatred and tradition. He is officially recognised as the national poet of Bangladesh and commemorated in India.

The birth date of Kazi Nazrul Islam, originally recorded on the basis of the Bangla calendar, is considered by some to be the 24th May 1899.

The Poverty Line

![]()

Revolution ? Pablo Bartholomew

The Poverty Line

Tarapodo Rai

I was poor. Very poor.

There was no food to quell my hunger

No clothes to hide the shame of my naked body

No roof above my head.

You were so kind.

You came and you said

‘No. Poverty is a debasing word. It dehumanizes man.

You are needy.’

My days were spent in dire need.

My needy days, day after day, were never-ending.

As I grew weaker

Again you came.

This time you said.

‘Look, I’ve thought it over,

“Needy” is not a good word either.

You are destitute.’

My days and my nights, like a deep longing sigh,

Bore my destitution.

Cowering in the burning heat,

Shivering in the cold winter nights,

Drenched in the never-ending rains.

I went from being destitute to greater destitution.

But you were tireless.

Again you came.

This time you said

‘There is no meaning to this destitution.

Why should you be destitute?

You have always been denied.

You are deprived, the ever deprived.’

There was no end to my deprivation.

In hunger and in want, year after year,

Sleeping in the open streets under the relentless sky

My body a mere skeleton

Was barely alive.

But you didn’t forget me.

This time you came with raised fist

In your booming voice, you called out to me.

Rise, rise the exploited masses.

No longer did I have the strength to rise.

In hunger and in want, my body had wasted.

My ribs heaved with every breath.

Your vigour and your passion

Were too much for me to match.

Since then many more days have gone.

You are now more wise, more astute.

This time you brought a blackboard.

Chalk in hand, you drew this glistening bright long line.

This time you had really taken great pain.

Wiping the sweat from your brow, you beckoned me.

‘Look. See this line.

Below, far below this line, is where you belong.’

Wonderful!

Profusely, Gratefully, Indebtedly, I thank you.

For my poverty, I thank you.

For my need, I thank you.

For my destitution, I thank you.

For my deprivation, I thank you.

For my exploitedness, I thank you.

And most of all, for that sparkling line.

For that glittering gift.

O great benefactor!

I thank you.

Translated from Bangla by Shahidul Alam.