A Photo-Forensic Study

Part of the “No More” public awareness campaign of Drik.

Let me ask a silly question, my partner Rahnuma had said. “But isn’t it all in your imagination” Of course it was. The images I’d created, while based upon complex scientific procedures, did not ‘prove’ anything. The objects I had photographed, while silent witnesses, had not ‘seen’ the crime. The artifacts, interviews, videos and photographs I was presenting were not ‘evidence.

I’d grappled with the question. It was as if Kalpana herself was a figment of our imagination. This fiery, courageous, outspoken young woman, who had dared to demand that she, as an indigenous woman of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, also had rights; had the audacity to speak out against military occupation by her own army; had the temerity to insist that as a citizen of a free nation, she too needed to be treated as an equal; was something the state wanted us to forget. Most of all, they wanted us to forget that seventeen years ago, in the early hours of the morning of the 12th June 1996, she had been abducted at gunpoint by our own military.

Many versions have been presented. That it hadn’t really happened, though there were numerous witnesses. That she had eloped and had been found in India, though there was not a shred of evidence to back the claim, that Lieutenant Ferdous, the principal accused in the abduction, hadn’t even been there.

Split along clear divides between the indigenous Paharis and the ‘plainland’ Bangali ‘settlers’ very different stories are presented. What is significant, however, is that only one version, that of the military-backed Bangali ‘settlers’, seems to have been taken into account. That until today, seventeen years to her abduction, Lieutenant Ferdous has never been questioned by the police. That next to Kalpana, Lieutenant Ferdous has been the only key player we have been unable to trace. The military, it appears, has no record of him. He too has ‘disappeared’.

What does an artist do to get an idea across? How does a journalist approach a story? How does a scientist investigate? This body of work, relying hugely upon the support of an international team of scientists, journalists, technicians, printers, fellow photographers and particularly the research, relationship building and friendship of an incredible co-worker, and indeed, co-author Saydia Gulrukh, attempts to combine all three approaches.

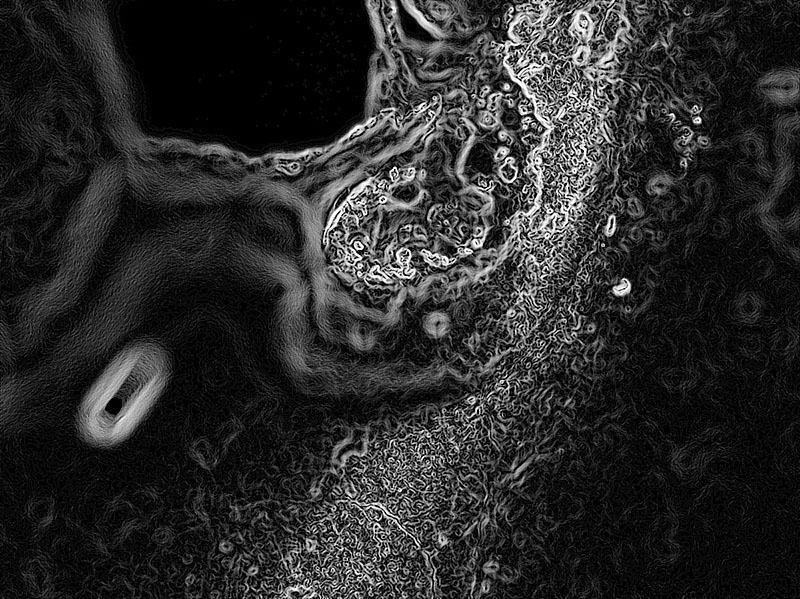

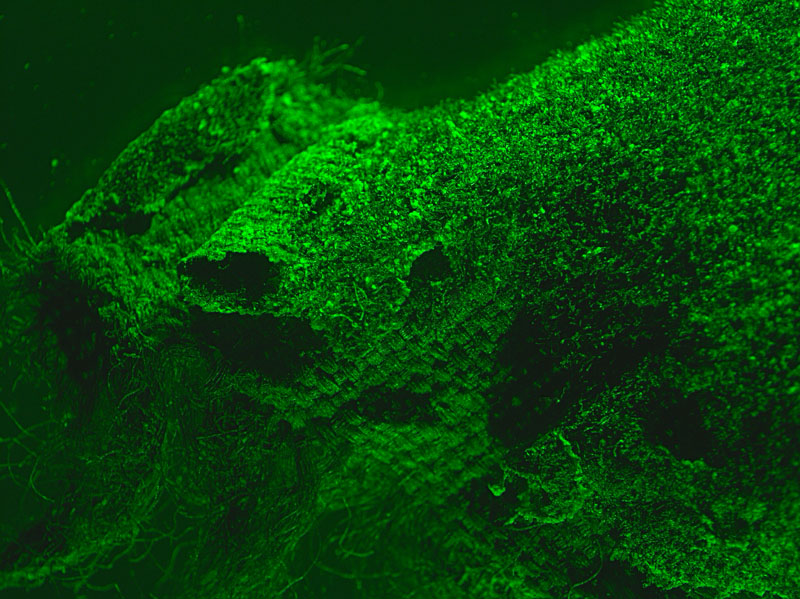

As an artist I have imagined. What might the tree that she may have leaned upon, when she had cried out the last words ever to have been heard from her “dada more basa” (brother save me), have seen? Had they made contact? Had she clung on to the bark one last time? Had a torn bit of fabric lingered on a thorny leaf? Has the sweat on her palm left an organic stain?

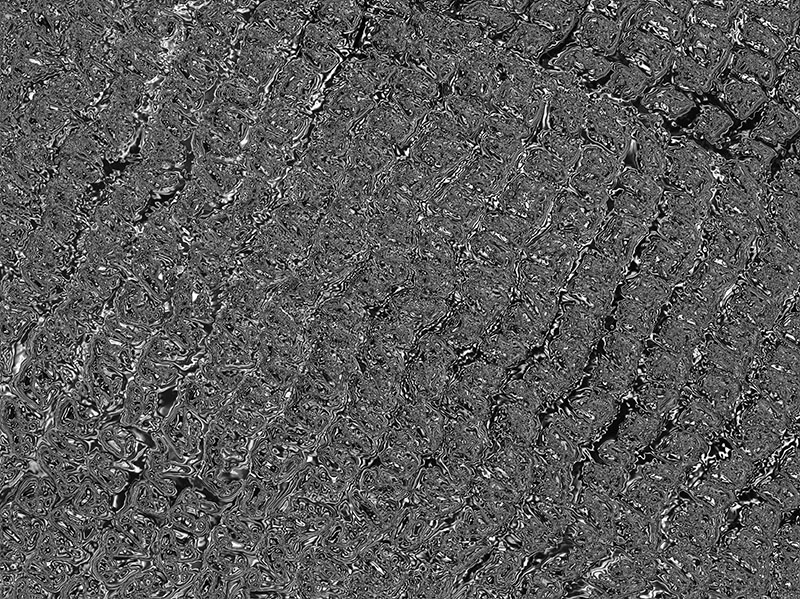

What secret did the soil on her worn shoe hold as it yielded to her weight and that of the military boots that fateful night? Did the muddy swamp, where the footprints had left their mark, know what the courts were unwilling to hear? Did the diary written in her own hand, with quotes and observations of a revolutionary who championed her people’s freedom, hold the words that would give a clue? Did the leaf by the bazaar where she had had the altercation with Lieutenant Ferdous, silent amongst many human witnesses who were able to speak but stayed quiet or whose words were ignored, say what others couldn’t?

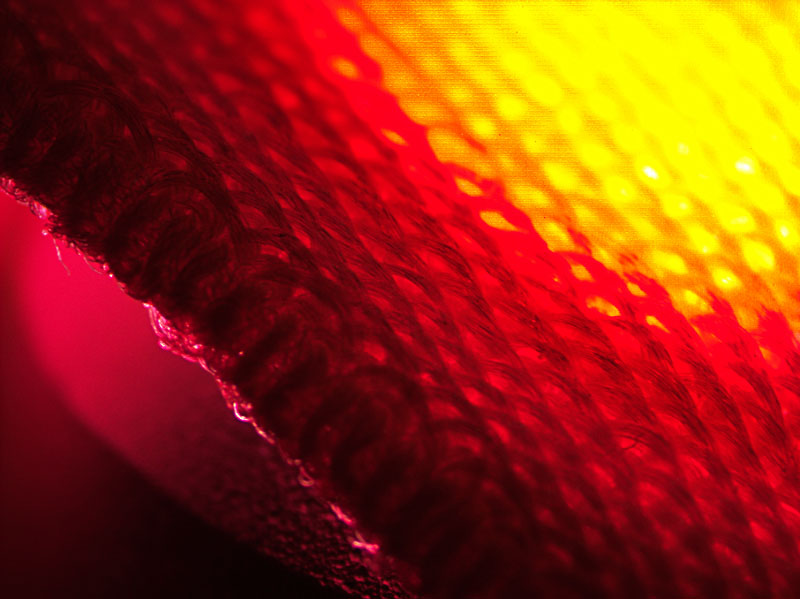

Is Kalpana’s mosquito net, witness to the last moments when she was in her home, able to tell us how it really was? As an artist, I have used my imagination to try to listen to their stories. As a photographer, I have tried to produce tangible visuals of a scene that has been made intangible, through the passage of time, through the deliberate ‘loss’ of crucial evidence, through the layers of bureaucracy that has allowed silt to collect.

As journalists, Saydia and I have tried to follow every lead possible, through every means possible, to speak to every key player in the story. To overcome fears of repercussions, to revive lost contacts, to build trust, to trace obscure links. We’ve located documents that were inaccessible. From the paharis to the settlers, from government officials to military bigwigs, from lawyers to local bystanders, we have searched for clues wherever the slightest lead existed.

As a scientist, I have used the full spectrum of forensic options, relying upon a global team of experts all across the globe and working in sophisticated laboratories in Falmouth, Oldenberg and Brisbane. As a photographer, I have extracted visual fragments using lights, filters and lenses to get the data to yield images. Working in Tokyo, using printing techniques not yet made public, I’ve rendered on paper imagery that describes, in light and shade, what those silent witnesses have tried to say.

I’ve relied upon Saydia as a social scientist, as a fellow journalist, as a tenacious researcher, as an engaged and committed activist and as a warm and loving friend to build bridges I would have found impossible to build. To piece together data, I would have found unconnected, to build trust where I would otherwise have been a stranger. Through her I’ve come to know Kalpana, the sister neither of us has seen. As fellow citizens, we have asked questions and tried to find answers.

We have tried to break a silence our governments, whether civilian or military-backed, have carefully nurtured for seventeen long years.

——————————————————————————————————

The project is hugely indebted to a large number of co-workers in Australia, Bangladesh, Germany, Japan and the UK. In particular, to Professor David Vaney and Professor Reto Weller, Mark Wallwork, Alan Hill, Colin Macqueen, Luke Hammond, Yoichi Niiyama, Anisur Khondokar, Samari Chakma, Swadhin Sen, Rahnuma Ahmed, and countless others who choose to remain anonymous have also played an invaluable role. Particular appreciation is also due to the curator ASM Rezaur Rahman and Foysal Ahmed and Zakir Hossain at the Drik Gallery as well as the entire team of the publication and printing department at Drik and my assistant Saleh Ahmed.

——————————————————————————————————- Photographs were taken using a Zeiss StereoDiscovery V8 Stereo Microscope – Plan S 1.0x objective and a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 Upright Microscope – Plan Neofluar 5x objective. 405nm fluorescence excitation. 420-480nm fluorescence emission at the Queensland Brain Institute in Brisbane, Australia.

The exhibition is part of a public awareness campaign called “No More”. It started with the show on extrajudicial killings “Crossfire” shown in 2010 and included exhibitions on the disasters on the garment factory deaths.

What a story! And how beautifully and movingly done. Gentle but powerful; shocking us to action. Reminds us, too, of other stories that went untold, often at the cost of so many lives. Such as the floods of 1974, denied until they were costing so many lives they could not be hid… Congratulations and heartfelt admiration. Good luck at the show; wish I could be there at House 58

God is true, so true is abduction of Kalpana Chakma, my sister in the hills. If God is here, Kalpana must be here, and the ultimate truth shall install her here, now and hereafter.

I’m disappointed I won’t been in Dhaka for the exhibition and wish everyone involved a successful opening.

Your images and words are both powerful and moving. Thank you for undertaking this project and sharing your work with the world.

Deeply moving. A frightening story. I hope Kalpana Chakma did not/is not suffering and your work highlights the plight of so many people… taken, without trial and lost to family and friends. We owe it to Kalpana to campaign for a better world, where people don’t dissapear. You have my sincere admiration and respect for your work.

This is a new power. A new move to break up the silence… Justice never be given up!

Beautiful and tragic. Further evidence that truth, justice, love, and beauty go together well. I’m comforted by the song lyrics, “to live in the hearts of those that you love is not to die,” (Badly Drawn Boy, 2004), knowing Kalpana lives on in your photographs and the memories of her family and friends.