Andre Vltchek, Counterpunch, USA, 16 March 2012

Fifteen years ago, in 1997, my Haitian friends helped to arrange my visit to Cite Soleil, then the largest and the most brutal slum (or ?commune?) in the Western hemisphere, at the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. The arrangement was simple: my F-4 camera and I were to be loaded on the back of the van. The driver and two guards promised to take me there for a two-hour photo shoot. The condition was simple: I was supposed to stick to the back platform of the pickup truck.

Once we arrived, I broke the agreement: I simply couldn?t resist the temptation. I jumped from the van and began walking; photographing all that was in the radius of my lenses.

The guards refused to follow me and when I came back to the intersection, the van was gone. I was later told that my driver was simply too scared to remain in the area. The reputation of Cite Soleil was and probably still is that one could easily enter, but could never leave.

Abandoned, young and moderately insane, I continued working for more than two hours. I encountered no hindrance: locals appeared to be stunned seeing me walking around with professional camera. Some were smiling politely; others were waving, even thanking me.

At some point I noticed two Humvees and the US military men and women with the machine guns facing a desperate crowd. Local people were queuing to enter some compound behind tall walls and the US soldiers were screening those who could be eligible.

Nobody bothered to screen me ? I just walked in with no interference. One of the US soldiers even gave me an enormous grin. What I found inside, however, was far from hilarious: a Haitian middle aged woman was laying on her stomach on some provisory operation table, her back split open, while several US military doctors and nurses were poking into her body with scalpels and something that appeared like pliers.

?What the hell are they doing?? I asked her husband who was sitting nearby, his face covered by palms of his hands. He was crying.

?They are removing her tumor?, he said.

There were flies all over, as well as certain much mightier species of insects that I never had a chance to encounter before. The stench was nauseating ? that of illness, open bodies, blood and disinfectant.

?We are training for the combat scenario?, explained one of the military nurses. ?Haiti is as close to real combat as one could get.?

?These are human beings, buddy?, I tried to argue, but he had his own way of looking at this. ?We don?t come, they die. So we are helping them, in a way.?

All I could do was to photograph the mess. No diagnostic equipment was used to determine what was really wrong with the patients. No x-rays were taken. I took a mental note that animals in almost any urban veterinarian clinic in the US were definitely treated much better than those unfortunate people.

Surgery in a Haitian camp. Photo by Andre Vltchek.

The lady was in pain, but she didn?t dare to complain. They were operating on her with only local anesthesia. After it was over, they stitched up her body, and put bandages around her body.

?What now?? I asked her husband.

?We will take a bus back home?, he replied.

Eventually the lady had to get up and walk, leaning on her husband who was lovingly supporting her. I couldn?t believe my own eyes: the patient was made to walk after having her tumor removed.

I befriended a doctor who eventually took me to the series of tents that served as a military installation for the US soldiers and staff deployed in Haiti. Facilities were air-conditioned, spotless, equipped with a real operation theatre, and above all, empty. There were dozens of comfortable cots available.

?Why don?t you let your patients stay here?, I asked.

?Not allowed?, replied doctor.

?You use them as guinea pigs, don?t you??

He didn?t reply. He considered my question to be rhetoric one. Soon after, I arranged the car and left.

* * *

I never managed to publish the story, except in one newspaper in Prague. I sent photos to the New York Times, to the Independent, but received no reply.

I was not really surprised as one year earlier, after hanging from the ceiling with my arms tied in some god-forsaken Indonesian military facility in occupied East Timor, and after being finally released with the words of ?We didn?t realize that you were such an important man? (they found a letter from the ABC News stating that I was on a research assignment as an ?independent producer?) I couldn?t find any Western mass media outlet that would show interest in publishing reports about mass rapes and other atrocities the Indonesian military had been routinely unleashing against the defenseless population of East Timor.

But several others already described this type of scenario before me, including Noam Chomsky and John Pilger. One could easily summarize the dogma of ?free Western press? as: ?Only those atrocities that are serving geopolitical and economic interests of the West could be consider as the true atrocities and would be allowed to be reported and analyzed in our mass media outlets.?

But for this article I would like to look at the situation from slightly different angle.

* * *

In 1945, this report appeared on the pages of Express:

THE ATOMIC PLAGUE

?I Write This As A Warning To The World?

DOCTORS FALL AS THEY WORK

Poison gas fear: All wear masks

Express Staff Reporter Peter Burchett was the first Allied staff reporter to enter the atom-bomb city. He traveled 400 miles from Tokyo alone and unarmed [this was incorrect but the Daily Express could not know that] carrying rations for seven meals ? food is almost unobtainable in Japan ? a black umbrella, and a typewriter. Here is his story form ?

HIROSHIMA, Tuesday.

In Hisroshima, 30 days after the first atomic bomb destroyed the city and shook the world, people are still dying, mysteriously and horribly ? people who were uninjured by the cataclysm ? from an unknown something which I can only describe as atomic plague. Hiroshima does not look like a bombed city. It looks as if a monster steamroller had passed over it and squashed it out of existence. I write these facts as dispassionately as I can in the hope that they will act as a warning to the world. In this first testing ground of the atomic bomb I have seen the most terrible and frightening desolation in four years of war. It makes a blitzed Pacific island seem like an Eden. The damage is far greater than photographs can show.

In Burchett?s report there were no footnotes and almost no quotes. He came to Hiroshima ?armed? with his pair of eyes and ears, with his camera and the tremendous urge for defining and describing some of the most appalling chapter in contemporary human history.

That?s how it was done in those days: journalism was a passionate activity, and a war correspondent had to be bright, brave and extremely quick. It was also expected from him or from her to be independent.

Burchett was one of the best, maybe the best and he had to pay very high price, as at one point he had been declared ?an enemy of Australian people?, even stripped of his passport. He wrote about the US atrocities against the people of Korea during the Korean War, about the US atrocities against its own soldiers (after being exchanged, those prisoners of war who would dare to speak about the humane treatment they received from their North Korean and Chinese captors, were often taken away, brainwashed, even tortured). He also wrote about the courage of Vietnamese people who fought for their freedom and ideals against the mightiest military power on earth.

What is remarkable is that even as he had to live in exile, even as his children had to be born outside Australia because of the vicious political witch-hunt unleashed against him, in those days there were still many publications ready to print his extraordinary writing. There were periodicals and publishing houses commissioning his reports and books, and then publishing them and to paying for his work.

It is obvious that in those days the censorship was not as absolute and consolidated as it is now.

What is even more remarkable is that he did not have to constantly defend what his eyes saw and his ears heard. His work was original and groundbreaking. He was not forced to quote countless sources, indexing everything that he was going to publish. He was not asked to recycle others. He came to the place he wanted to describe, he spoke to people, got some important quotes, described the background and then the story would get published.

There was no need to quote some ?Professor Green? saying that it was raining if Burchett knew and saw that it really was. No need for some ?Professor Brown? to confirm that the ocean water was salty or that earth was round.

It is impossible to write like this now. All individualism, all passion, and all intellectual courage disappeared from the mass media reporting and from the great majority of non-fiction books. There are almost no manifestos, and no j?accuse. Reports are restrained, made ?safe?, ?inoffensive?. They don?t provoke readers; don?t send them to the barricades.

* * *

The mass media monopolizes the coverage of the most important, the most explosive topics of today: the wars, occupations and the horrors that billions of people of the world have to suffer as a result of our neo-colonialist regime and its market fundamentalism.

The independent reporters are not being hired, anymore. Those who are still around and working are well ?tested? and even then, the numbers are much smaller than several decades ago.

It all makes sense. Coverage of the conflicts is the core of ?ideological battle? and the propaganda mechanism of the Western globally imposed regime is fully in control of it. Naturally it would be na?ve to believe that the mainstream media and academia are not essential parts of the system.

To understand the world in depth, one has to be familiar with the plight and horror of the wars and conflict zones. That?s where the colonialism and neo-colonialism are showing their awful and sharp teeth. And by the conflict zones I don?t only mean the places that are bombed from the air and shelled by artillery. There are ?conflict zones? where tens of thousands, even millions of people are dying as a results of sanctions, misery or internal battles fueled from outside (like in the present day Syria).

In the past, the best coverage of such conflicts was done by independent reporters, most of them coming from the ranks of progressive writers and independent thinkers. The stories and images of the wars, coups and plights of the refugees were on the ?daily menu?, served with the eggs and cereals to the citizenry of the culprit countries.

At one point, thanks to the independent reporters, the public in the West was becoming increasingly aware of conditions in the world.

Citizens of the Empire (North America and Europe) were given no place to escape the reality. Top writers and intellectuals were speaking on prime television and radio shows about the terror we were spreading around the world. Newspapers and magazines were regularly bombarding the public with anti-establishment reports. Students and citizens who felt great solidarity with the victims (that was before they became too busy with the Facebook, Twitters and other social media that pacified them and made them shout at the smart phones instead of trashing the city centers) were periodically marching, building the barricades and fighting security forces on the streets. Some, inspired by the reports they read and watched, were travelling abroad, not just to hit beaches but to see with their own eyes the living conditions of the victims.

Countless independent reporters were Marxists but some were not. Many of them were brilliant, passionate and unapologetically political. Most of them were never pretending to be ?objective? (in a sense implanted by today?s Anglo-American mass media, which insists on quoting several ?diverse? sources, but suspiciously leads their stories to uniformed conclusions). They were mostly intuitively antagonistic to the Western imperialist regime.

As even then there was consistent flow of propaganda disseminated by well-paid (and therefore well disciplined) reporters and academics, the independent reporters, photographers and filmmakers were heroically serving the world by producing an ?alternative narrative?.

Among them there were people who decided to exchange their typewriters for weapons, like in case of Antoine Exupery. There was Hemingway holed in Madrid, drunkenly damning Spanish Fascists in his reports, while later endorsing the Cuban Revolution and providing it with the financial support. There was Andre Malraux who, while covering Indochina, managed to get arrested by the French colonial authorities and later launch an anti-colonialist magazine. There was Orwell and his intuitive disgust for colonialism and then there were the masters of war and conflict-zone journalism: Ryszard Kapuscinski, Wilfred Burchett and lately John Pilger.

There is one very important point to be made about them and about hundreds of others: they were able to support themselves ? they lived, travelled and to worked ? from the incomes their reports were generating, no matter how anti-establishment their work had been. To write great articles and books was a solid profession; in fact one of the most respectful and exciting professions one could hope for. What they were doing was seen by society as essential service to humanity. In those days they were not expected to teach or to do something else in order to survive.

* * *

Things definitely changed in the last few decades!

Today it feels like we are living in a different universe when we read from the book of Ryszard Kapuscinski, The Soccer War.

It is 1960, Congo previously plundered by Belgian colonizers (it lost millions in the most brutal reign of King Leopold II and after) gains independence and the Belgian paratroopers arrive: ?the anarchy, the hysteria, the slaughter?.

Kapuscinski is in Warsaw. He wants to go (Poland gives him enough hard currency to travel) but he has Polish passport and in yet another proof of great Western love for freedom of speech and information, ?everyone from the socialist countries is being thrown out of the Congo?. Kapuscinski flies to Cairo. He teams up with Czech journalist Jarda Boucek. They decide to go via Khartoum and Juba:

?In Juba we will have to buy a car, and everything that will happen after that is a big question mark. The goal of the expedition is Stanleyville, the capital of the eastern province of the Congo, in which the Lumumba government has taken refuge (Lumumba himself has already been arrested and his friend Anoine Gizenga is leading the government). I watch as Jarda?s index finger journeys up in Nile, stops briefly for a little tourism (here there is nothing but crocodiles; here the jungle begins), turns to the south-west, and arrives on the banks of the Congo river where the name ?Stanleyville? appears beside a little circle with a dot in it. I tell Jarda that I want to take part in this expedition and that I have official instructions to go to Stanleyville (which is a lie). He agrees, but warns me that I might pay for this journey with my life (which later turns to be close to the truth). He shows me a copy of his will, which he has deposited with his embassy. I am to do the same.

What this fragment of the book indirectly shows is that those two adventurous and brave reporters had full confidence in what is waiting back in their home countries (Poland and Czechoslovakia). They were following the most important story of the greatest African pro-independence figure, Patrice Lumumba, a man who had been eventually slaughtered by joint Belgian ? US efforts. (Lumumba?s assassination tossed Congo to hell that is lasting until the very day when this article is written). They were not sure that they would survive the journey, but they were confident that their work would be respected and enumerated. They had to risk their lives, use their ingenuity, and to write brilliantly. But the ?rest was taken care of?.

The same was true about Wilfred Burchett and to some extent of several other brave reporters who dared to cover the Vietnam War independently, hitting hard at the public conscience in Europe and North America, not allowing the passive mainstream of citizenry to later claim that ?they did not know?.

That era did not last forever. Mass media outlets and opinion makers of the Empire eventually realized that this sort of writing is unacceptable as it only creates dissidents and people who are searching for alternative angles and sources of information, in the end undermining the regime.

When I read Kapuscinski, I am involuntarily thinking about my own work in DR Congo, in Rwanda and Uganda.

Once again, one of the most important stories in the world is taking place in Congo. 6 to 10 million people have already died, a result of Western greed and unbridled obsession with controlling the world. The entire historic narrative twisted, two appalling African dictatorships fully supported by the US and UK are murdering and plundering Congo on behalf of the West and its companies.

Whenever I risk my life there, whenever I am being thrown to some hole from which I know I may never leave, I know there is no ?home base? waiting for me or backing me up. I get out because of some UN ID, because of some impressive (to my captors, but not to me) piece of accreditation. My work as an investigative journalist or a filmmaker guarantees nothing. I am not sent by anybody. Nothing is paid. I am on my own.

When Kapuscinski used to return home, he was welcomed as a hero. Half a century later, those of us who do the same work are nothing more than outcasts.

* * *

At one point, most of the major newspapers and magazines, as well as television channels, stopped relying on brave, mildly insane and independent ?freelancers?. They went on a hiring spree, turning reporters into corporate employees. Once this ?transition? had been achieved, it was extremely easy to convey to the ?employees? still called ?journalists? how to cover the events, what to write and what to avoid. Often nothing had to be said in detail ? corporate staff is known to get things intuitively.

Funds for hiring independent writers, photographers or producers on freelance basis were cut drastically. Or they disappeared altogether.

Many starved freelancers were forced to apply for jobs. Others began writing books, hoping to keep the information flowing. But very soon they were told that ?these days there are no money in books, either?. The best was to apply for ?teaching jobs?.

Several universities were still absorbing and tolerating some degree of intellectual dissent, but the price they ?charged? was steep: former revolutionaries and dissidents could teach but were allowed no emotional outbursts, no manifestos, no calls to arms. They had to ?stick to the facts? (the way the facts were now customarily presented); they had to begin recycling thoughts of their ?influential? colleagues, to overflow their books with quotes, indexes, and indigestible over-intellectualized pirouettes.

And by then we were already entering the Internet era. Thousands of sites popped-up but many great alternative and Left wing paper publications had to close down. After few years of enthusiasm and hopes it became clear that the regime and its mass media consolidated control over the brains of the public with the help of Internet, not despite it. Main search engines implanted mainstream right-wing news agencies to the front pages. Unless the individual really knew what he or she was looking for, unless he or she was very educated and very determined, there was very little hope to just stumble over opposition coverage or interpretation of the world and local events.

Now, most in-depth articles had to be written with no funding, as if writing them has become some sort of a hobby.The glory of war correspondence was over, the grandeur of the adventure called search for truth gone all replaced with hipness and ?lightness?, social networking, entertainment.

The bliss of ?lightness? was at first reserved only for those in the driving seats ? for the citizens of the Empire and for outrageously corrupt (the West?s doing) elites in far away colonies. Needless to say, the majority of the world has still been submerged in extremely ?heavy? reality, mostly living in the shantytowns serving colonial economic interests, surviving in brutal dictatorships implanted mercilessly and then sadistically sustained by Washington, London or Paris.

But eventually, even many of those dying in slums of Southeast Asia and Africa were successfully injected with the lightness, with entertainment drug, and with absolute spite for serious analyses of their own condition.

* * *

Those few independent writers who were still left fighting ? the war correspondents educated on the works of Burchett and Kapuscinski ? were losing both the audience and the means to perform their work.

Practically, to cover wars, to cover real conflicts, is extremely expensive, especially if they are to be covered thoroughly. One has to deal with unreasonably pricey tickets on chartered or erratic flights, with heavy professional equipment, with bribes one has to spread in order to get anywhere near the action, with constant changes of plans, and with delays. One has to arrange visas and permits. One has to communicate and once in a while one gets injured.

The access is now much more controlled than in the days of the Vietnam War. While I still managed to get myself to the front line in Sri Lanka some ten years ago, it would be unthinkable in the later years of the conflict. Although I had been successfully smuggling myself to East Timor in 1996, those independent reporters who are now trying to sneak in to Papua where Indonesia ? great partner in crime of the West ? performs yet another genocide are regularly arrested, imprisoned and deported.

In 1992 when I covered the war in Peru, once I got my accreditation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it was basically up to me whether I wanted to stay in Lima or to risk my life and drive to Ayacucho, fully aware that the military or Sendero Luminoso could choose to blow up my brains on the way (which once actually almost happened).

But in these days to enter Iraq or Afghanistan, or any place that is occupied by the US and European forces would be close to impossible, especially if the aim would be to investigate crimes against humanity committed by the Western regime.

Frankly: these days it is hardly possible to get anywhere, unless you are what they call it ?imbedded? (actually a very colorful but correct description: you let ?them? do it to you and ?they? let you write, as long as you write what ?they? tell you). To be allowed to cover the war a reporter would have to have some mainstream; some powerful organization covering his or her back, getting required accreditations and passes, and vouching for the writer?s output. Independent reporters are considered unpredictable and they are therefore unwelcomed.

There is a way to sneak in to several conflict zones. Those of us with years of experience know how to do it. But imagine that you are ?on your own?, that you are volunteering, writing almost for free. Unless you are independently wealthy and willing to spend it all on your own writing, you better analyze things ?from the distance?. And that?s exactly what the regime wanted to achieve: no first hand reports from the Left. Only ?rambling? from far away.

* * *

As if the bureaucratic and institutional barriers erected by the regime would not be sufficient to prevent some hardened independent reporters (from those few who are still around) from visiting the conflict areas, the financial barriers are always ready to kick in: almost no one outside the mainstream media is able to match the fees of drivers, fixers and interpreters inflated by the corporate media operating on the expense accounts.

The result is clear: the opposition to the neo-colonialist regime is losing the media war as it is unable to bring reporting from the places where the Empire is continuously committing genocides and crimes against humanity to the wider public. As we established earlier, recently there is no unceasing flow of images and dispatches that would bombard the millions in culprit nations ? a flow similar to the one that managed to outrage and shock the public and stop the Vietnam War several decades ago.

Consequences are shocking. European and North American public is generally unaware of even the most appalling horrors that are taking place around the world. One of them is brutal genocide that is taking place against the people of DR Congo. Another is the terrible destabilization campaign again Somalia, with almost one million refugees literally rotting in overcrowded camps in Kenya (I recently made 70 minutes documentary film ?One Flew Over Dadaab? on the topic).

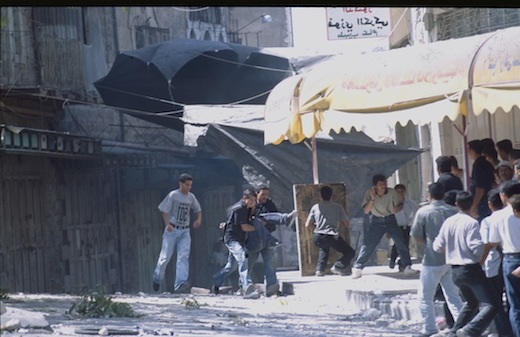

There could be hardly any words available to describe the cynicism of Israeli occupation of Palestine, but the US public is fed with ?objective? reports and is therefore ?pacified?.

While the propaganda machine is being unleashed against all countries that stand firm against Western colonialism ? China, Russia, Cuba, Venezuela to name just a few ? the crimes against humanity committed by the West and its allies (including Uganda, Rwanda, Indonesia, India, Philippines, Colombia and many others) go unreported.

Millions are displaced; hundreds of thousands are killed, due to the Western geopolitical maneuvers in the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere. Very little had been reported on disgraceful destruction of Libya in 2011 (and on the terrible aftermath) and on the way the West had been tirelessly working to overthrowing the government in Syria.

There is hardly any reporting on how Turkish ?refugee camps? on the Syrian border are actually used to feed, train and arm Syrian opposition, the fact well documented by several leading Turkish journalists and filmmakers. Needless to say, for independent Western reporters such camps are off limit, as my colleagues in Istanbul recently explained me.

* * *

While there are several great publications like CounterPunch, Z and New Left Review, those thousands of ?displaced? independent war correspondence should have more domiciles they could call ?home? or ?institutional home?.

They are great assets, great potential guns and ammunition in the fight against imperialism and neo-colonialism. That?s why the regime made sure to sideline them, to make their work irrelevant.

But without their knowledge, no objective analyses of the present global conditions are possible. Without their reports and images, both victims and victimizers would not be able to understand the depth of insanity into which the world has been thrown.

Without them, as millions of human lives are being lost and billions lives ruined, the citizenry of the Empire could still be dying of laughter in their entertainment parlors and with the electronic gadgets in hands, once again fully ignoring terrible smoke coming from proverbial funnels. And in the future, if confronted, they would be able to say again, as they did so many times in the history: ?We didn?t know?.

- Andre Vltchek is a novelist, filmmaker and investigative journalist. He lives and works in East Asia and Africa. His latest non-fiction book ?Oceania? exposes Western neo-colonialism in Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia. Pluto in UK will publish his critical book on Indonesia ? (Archipelago of Fear) ? in August 2012. He can be reached through his website.

From: http://www.counterpunch.org/2012/03/16/the-death-of-investigative-journalism/

[url=http://www.louboutin-outlets.com]http://www.louboutin-outlets.com[/url] fsig

[url=http://www.windows7productshop.com]www.windows7productshop.com[/url] yfha