by rahnuma ahmed

Everyone, regardless of whether they belonged to the Awami League or to the BNP or Jamaat,?or was an ordinary citizen, suddenly became a Muslim.

— Adnan Wahid

HE WAS speaking of September 29, 2012, trying hard to explain to us, as we sat at a cafe in Dhaka, of how it could have been possible for local Bengali Muslims — who had lived peacefully with Buddhists, both Bengalis (Barua) and Rakhains, for many generations??in Ramu — to take part in wave after wave of assaults which destroyed innumerable Buddhist monasteries and temples where neighbours had worshipped and prayed, to take part in armed attacks which set fire to houses where Buddhist neighbours had lived.

Things were different in Ramu, as far as I can tell we’d always been different from people in other places, what mattered most, what we’d always been proud of, was that we belonged to Ramu.?We were Ramu-bashis. But the September 29 attacks have shattered our feelings of collectivity, they have struck a terrible blow at our bonds of togetherness.

Many Buddhists in Ramu confided to us, it’s not like before, we don’t know if it’ll ever be the same again. People have received threats over the phone, especially those who spoke to the media, spoke to outsiders who rushed to Ramu after the violence, “how long will the police and BGB (Border Guards Bangladesh) protect you? See what happens after they leave.”

It all depends on whether the guilty are punished, they said, asking me worriedly, what do you think? Will they be punished? I was forced to lower my eyes, even though I knew my silence added to their uncertainties, for, on what grounds could I utter words of reassurance?

A Rakhain schoolteacher told us, a group of young men armed with sticks and swords rushed into our neighbourhood. I heard voices say, those are Hindu homes, hey, no, those ones are Muslims. Of course locals were involved, how else could they have known which ones to attack? Another Buddhist, a young Barua man, in the middle of a long conversation thoughtfully said, even though it’s been a fortnight, I find it difficult to get back to work. I call my boss each morning and say, sorry, I can’t make it today, I’ll definitely be in tomorrow. But I haven’t, I just can’t concentrate, I feel restless. I meet Muslim friends in the streets, they ask me, “Ki khobor?” Good, I reply, but I don’t look them in the eyes. It’s all changed. (I conceal names of all Buddhists I spoke to, out of concern for their security).

Ramu-bashis are now divided into “Muslims” and “Buddhists.” Into “attackers” and “attacked.” Into those who stood by, and those who failed. Everything has changed.

The incident which is reported to have sparked off hours of unfolding violence in Ramu was the discovery of an offensive picture on the Facebook wall of Uttam Kumar Barua, a Buddhist youth. It showed the feet of a girl (how do you know it was a girl? because ‘her’ toes had nail polish, I was told) planted squarely on the open pages of a copy of the holy Quran. News of this discovery which was made by Muktadir, a polytechnic student, spread quickly;??it travelled outside the small computer shop located in Fakirabazar, Ramu town, owned by Faruk, Uttam’s FB friend. It was a market day, crowds thronged the bazar, and soon enough, a small group of Muslim men entered the shop, including two who were reportedly strangers. They were curious, they wanted to see the offensive photograph.

The Facebook page, with Uttam Kumar Barua’s profile, was saved and photographed, photocopies of the page bearing the picture were later distributed. It incited anger and hatred. Local boys and men gathered after?esha?(nighttime) prayers at Choumuhoni Chottor (Ramu’s town centre), processions of 50 or so, marched up and down the town streets before circling back to Choumuhoni, they chanted slogans against the alleged??offender: “Uttam Barua’r gale-gale, juta maro tale-tale” (Slap Uttam Barua on both cheeks with a shoe). “Quran akromonkarir shasti chai, fashi chai” (Punish and hang him for having attacked the Quran).

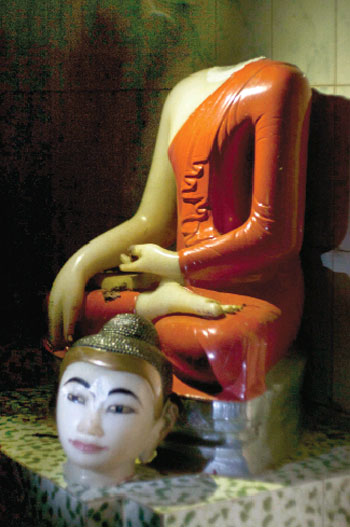

But there were other slogans as well, expressing a leap, a jump, from the individual to the community, one which constructed the entire community of Baruas (Bengali Buddhists) as being a unified whole, as being guilty of a crime which demanded collective punishment: “Baruader astana jalie dao, purie dao” (Set fire, burn down the dwellings of Baruas). The unified whole extended to include Rakhain Buddhists too, as Bengali Muslim men, mostly youths, poured into Ramu town, some on motorbikes, many in hired buses and trucks. The gathering at Choumuhoni swelled, speeches were delivered, the mood grew angrier; groups armed with sticks, curved swords, stones, gunpowder, petrol and home-made cocktails broke away and entered streets and lanes, they attacked Buddhist monasteries and temples belonging to both Baruas and Rakhains, they struck down statues of Lord Buddha, beheaded some, looted those made of gold, broke open donation boxes, helped themselves to the cash. Some moved from one monastery to another, other groups went directly to ones more distant from??Choumuhoni Chottor. They ransacked, looted and burned, their actions seem to have been well-coordinated.

Everyone seems to agree that the attacks were planned, pre-meditated, even the government and the major opposition party, the BNP, which might be a cause for celebration since they seem to agree on so little. And even though Uttam Barua is still in hiding, most agree that he is innocent, since the photo had been tagged to his FB account.

Harmony was instilled in us from childhood, says Adnan reflectively. My father would always tell us, “ami Musolmaner cchele kintu boro hoecchi Baruader ghore” (I am a Muslim boy but I grew up in Barua homes). Never forget this, he would tell us repeatedly.

Or, as a highly-educated Bengali Buddhist man told me, you don’t go out and make friendships on the basis of religious belonging, friendships are formed (dhormo dekhe to ar keu bondhutto korena, bondhutto to gore othe). Religious belonging is secondary. But his elderly parents, I was distressed to discover, had been forced to flee from their home, to take shelter in the woods behind their house when the Ramu Shima Bihar, located in their neighbourhood, not far from Choumuhoni Chottor, was set on fire.

Violence erupted in Ukhiya and Teknaf sub-divisional towns the next day because of the offensive photograph, which is said to be one of a stock of other equally offensive photographs, found on a website called Insult Allah. Hindu women and girls in Hoyaikong (Teknaf), afraid of being raped, took shelter in a nearby stream. They stood half-submerged in water until the attacking crowds had left, several hours later. We were reminded of 1971, the older ones said.

I myself am reminded of attacks on Hindu homes right after the 2001 parliamentary elections, generally known to have been committed by supporters of the Jamaat-e-Islami and the BNP. I am reminded of the mother in a Barisal village who had pleaded with the men who’d invaded her house. She’s so little, she’s only thirteen, one after the other please, I beg of you. I was reminded of Prashanta Mridha’s short story, based on the incident, where he’d drawn parallels with Saadat Hasan Manto’s partition story, of the worried-to-death Muslim father who had been separated from his daughter during the riots, of his being vastly relieved when his daughter was brought into the hospital. The doctor, unsure of whether the girl was dead or alive, instructed someone to open the windows, it’s stuffy in here.?Khol do. Her fingers quivered, her father was overjoyed that his daughter was still alive, but the doctor was aghast, for her fingers had imperceptibly moved down, to loosen her trouser string.

While recounting the violence in Ukhiya, Buddhists spoke of Muslim neighbours who had stood by them, who had rushed forward to protect them. “The principal of the madrasa behind the school next door, Moulana Abul Hasan Ali,” said a?bhante?(monk) of Raja Palong Jadi Bouddho??Bihar, “leapt over the wall and came charging down, I don’t know how he could, he’s so fat and heavy, but the minute the attackers saw him they ran away. They seemed to disappear into thin air.”??I was eager to meet the principal but we were on our way to Teknaf, dropping in at the madrasa would have delayed us.

Shameem Ahsan Bulu, son of professor Mushtaque Ahmad (founder, Ramu College) suffered pretty severe injuries because the?hujur?leading the attack on Baruapara in Ramu, had thrown a brick which hit him on the head. But there had been others as well, who had risked their lives to defend their neighbours from the attacks. “I don’t think any member of advocate Nurul Islam’s family was free of injuries, the whole family??rushed forward to save us, all his Barua neighbours took shelter in his home,” said a young Barua student. But his eyes looked vacant, staring apprehensively into the future. However they lit up a little later when he recounted another tale. A reporter who had come from Dhaka had pointed at a Barua boy and asked Shameem Ahsan, “who is he?” Bulu bhai had replied, “my nephew.” The reporter had been startled. A Muslim man with a Buddhist nephew.

Not all ties of good neighbourliness had frayed. Nor had all fictive kinship ties and the obligations they demand, collapsed.

Some had resisted the attackers out of religious convictions, ones put to practise, ones that were enacted, as we see happen in the case of Mohammad Moinuddin, assistant superintendent of Khorulia Talimul Quran Dakhil Madrasa and chairman of East Khorulia Sikdarpara Jame Mosque. I told believers who came to the mosque for Fazr prayers, of course you should condemn the act, but remember, “if?neighbouring Buddhist villages are attacked” you are obliged to protect them. Islam teaches us to protect those who are innocent. I was away in Cox’s Bazar but when I received frantic phone calls from villagers that night, they said, crowds had gathered in Khorulia, Buddhist homes were likely to be attacked, I rushed back. I was met by a crowd of 400-500 people, “all unknown.” I challenged them, I told them, I have studied the Quran and the Hadith. Nowhere does it say that a community can be held responsible for an offence committed by one of its members. But convincing them was not easy, they insisted, they were obliged to take “revenge.” I argued with them for about an hour, they relented only after I’d said, if they have sinned by not taking revenge, I would take “responsibility” for it on the Day of Judgment??(New Age?Xtra, October 12, 2012).

To return to the quote at the beginning of my column, “Everyone suddenly became a Muslim”, while I would fully agree that the statement itself calls for a lot of unpacking and deconstruction, for now, it is important to recognise how it resonates at the level of everyday cognitive action. Of how it creates a shared language post-attacks, through its ability to capture and convey both the sense of betrayal felt by Buddhists, and the feelings of guilt suffered by those Muslims genuinely opposed to the attacks. Both Buddhists and Muslims who I spoke to, repeatedly said, harmony was not lived through the absence of religious differences, we would go to their weddings, they would come to ours, food was exchanged on our Puja and their Eid,?didi–apa,?mashi–khala,?nomoshkar–salam, these flowed naturally. Nor was it unknown, confided young men, for a Muslim who relished crab to secretly request a Buddhist aunt, or, a Buddhist man wishing to eat beef, hop over to a Muslim uncle’s home.

Buddhists cite two instances, overheard, to illustrate how police officials of Ramu thana contravened their official pledge to protect all citizens, irrespective of religious belonging (constitutionally enshrined), in other words, how they “became Muslims.” The officer-in-charge of Ramu thana was overheard as having said at Choumuhoni Chottor, “my blood too is boiling” [because of Uttam Kumar’s alleged offence]; while another official belonging to the same thana had reportedly said, “if I had not been wearing this uniform [I too would have joined the attackers].” But there seem to be contrary instances as well, where members of law enforcing agencies, alongwith elected representatives of all major political parties, Awami League, BNP and Jamaat, had collectively fought off hundreds of processionists, bent on destroying the Buddhist temple in Joarikhola. I spoke to a UC member of Joarikhola village (Hoyaikong, Teknaf)??affiliated to the BNP, and the son of the president of the upazilla AL (the son is a former member of the Chatra League), who recounted how they, together with the upazilla chairman, Nur Ahmed Anwari, Jamaat leader, and local police officials had risked their lives to fend off the attackers. When I wanted to know where the upazilla chairman was, I was told he’d gone into hiding because he had been accused of instigating the torching of Hindu-Barua houses, of looting and vandalism (banglanews24. com, October 1, 2012). But, why? you say, he hadn’t..? Oh, its “political”, said the former Chatra League leader, a bit?embarrassed.

Every Buddhist monk I spoke to in Ramu had repeated these words of caution, we have been done wrong, it is necessary that the guilty be punished but it is also essential that the innocent should not be punished. It is against our religion; our monks in Ramu, I would like to add, were calm, unhurried and serene, a far cry from the ones I have watched on YouTube (before it was banned), participants in communal riots in Sittwe, Myanmar.

Members of the ruling Awami League, I was told, had advised some monks to name opposition political party leaders and members as having led the attack. But that would be a lie! replied the monks. When they still insisted, the monks reportedly said, okay, we will say we destroyed our own?monastery.

I now turn to the government’s response to the Ramu attacks, particularly to the report submitted by the high-powered probe committee formed by the Home Ministry.

To be continued

Published in New Age, Monday, November 12, 2012?Please Retweet #Ramuburns

Related stories on DrikNews:

Lord Buddha and temples burned, looted

Ramu observes Probarona Purnima with no fanush

What color is our “Blood & the Sky” we live under. If they are always the same, why should we be any different?to each

other.