Dr A.K.M. Abdus Samad, the director of the mental hospital in Hemayetpur, Pabna, was pragmatic. “An average of 2% of all populations are schizophrenic, and of course there are many other mental ailments. In this country of 130 million, we have one hospital with 400 beds. What do you expect? The government allocation for food is 18 Taka per day (about 45 US cents when we met in 1993). Many mental patients are hyperactive and need more food. A good portion of that 18 Taka goes to the contractor, the remainder has to provide three meals a day. So what can I do? I make sure they get plenty of rice. That way they at least have a full stomach. We have little money for drugs, and virtually no staff for counselling, so we keep them doped. Then they don’t suffer as much.”

The other doctors had a different take. “Pity you’ve come on a Friday they said. On a weekday we could have shown you an electric shock treatment.” It seemed to be a popular ‘treatment’. To the uninitiated like me, the violent convulsions and the near comatose state the patients lay in afterwards didn’t seem to be the way to treat anyone. The care givers differed. The treatment was generally given to suicidal patients they said, and the way they saw it, it was “better than letting them kill themselves.” I didn’t have much of an argument against that one.

I saw the group of visitors come round to the dorms at night and peep through the windows. It was well after visiting hours, but they had paid to get in and have a look at the ‘pagols’ (loonies). On Eid day, many would dress up and come to the peep show. Some patients did get visitors on Eid, a select few even got new clothes or special food, but for most, it was another day of waiting. Another day of hoping that someone close might come and take them away.

In every ward I went, someone would take me aside, and slip a note in my hand. Invariably, scrawled in that note would be an address. “You must take it to them (their relatives). Tell them I’m OK. Tell them to take me away from here.” The first few times I did try and contact those relatives. Some addresses had people who recognised them, most didn’t. None seemed keen on responding. Eventually I gave up, but I would still take the notes. In Hemayetpur, even false hope seemed something worth giving.

—————————-

As another Eid approaches, I remember the child Shoeb Faruquee had photographed in Chittagong. It won him an award at World Press Photo, but I wonder where the child is now.

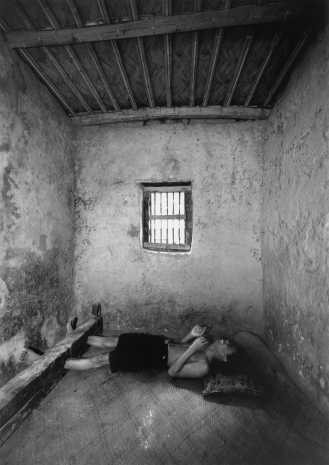

Patient at mental hospital, Bangladesh

? Shoeb Faruquee, Bangladesh, Drik/Majority World

Mohammad Moinuddin had yet another story to tell:

http://www.newint.org/columns/exposure/2006/08/01/md-main-uddin/

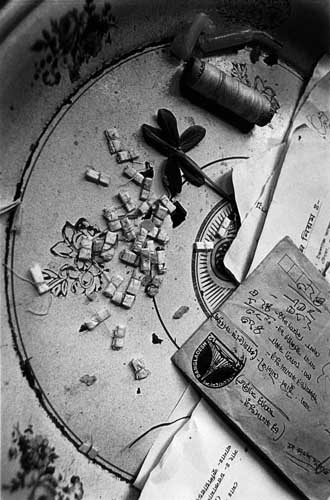

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh, Drik/Majority World

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh, Drik/Majority World

I was on an assignment at Domra Kanda, an asylum for the mentally ill in Kishoreganj, Bangladesh, where the only medications provided are these ?medallions? filled with spiritual spells and ?blessed water? from traditional spiritual healers. Illiteracy about medical treatments ? particularly those related to mental health issues ? misconceptions and limited health facilities mean that many parents resort to their faith in such medallions and other blessings from spiritual healers. The clinics which provide such traditional solutions do not offer scientific medications of any type and neither are they approved by any health authority. But for many Bangladeshis, faith in traditional healers and their treatments is more powerful, effective and easily available than scientific medication. The parents strongly believe that it is their faith in such spirituality that will cure their child and bring back the long lost peace and happiness to their family.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

In a world where normality is a virtue, I salute the few individuals who have chosen to be different.

Shahidul Alam

23rd October 2006. Dhaka

ps: Apologies to ZAK on my spelling of Eid: http://www.kidvai.com/zak/2005/11/its-that-time-of-year-again.html

6 thoughts on “On One Eid Day”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Shaidul Alam does these short pieces better than anyone else.

afsan

Dear Shahidul Alam,

I was touched by your text and pictures. My parents work with the mentally challenged (more down syndrome than schizophrenics) in Kolkata and have tried to change peoples’ perceptions of them by offering them a space where they can work making simple things like candles and cards and where they can participate in collective life through an exploration of their talents such as singing or dancing and praying together (its multi-faith). This instilling of a sense of self-worth has done much to make the mentally challenged more acceptable to their family and friends. The association they work in – called ‘Asha Niketan’ – is part of a larger International organisation called L’Arche founded by Jean Vanier. This organisation has recently branched to Bangladesh where it is known as ‘Ashanir’ (http://www.taize.fr/en_article3042.html)

Some people working on the mentally ill might like to visit them in MYmensingh or in Kolkata.

Again, thank you for bringing such sensitive issues to the fore and for the beautiful quote with which you end your piece: ‘In a world where normality is a virtue, I salute the few individuals who have chosen to be different.’

Truely inspiring!

Best Wishes

Annu

May Allah bless your work in bringing the truth to light, Brother. It seems like the Middle Ages in such facilities. Allah have mercy on them.

Ya Haqq!

good !!