The Loving Face of British Imperialism

rahnuma ahmed

…the [Nigerian] nationalist leader Nnamdi Azikiwe urged Africans and other colonized peoples to prepare their own blueprint of rights themselves instead of relying on those who are too busy preparing their own.

— Bonny Ibhawoh, Imperialism and Human Rights, p. 155.

Forced marriage, says a British High Commission press release, is a crime (British High Commission, ?The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office Forced Marriage Unit Launches National Publicity Campaign on Forced Marriage,? Dhaka, 28 March 2006. The link, for unknown reasons, has gone dead). As opposed to arranged marriages, forced marriages — by dint of not being based on consent — are a form of domestic violence and human rights abuse.

To increase awareness, both in Britain and abroad, the British home ministry (HO), and the foreign ministry (FCO), jointly formed a Forced Marriage Unit in January 2005. The unit was tasked with launching a publicity campaign: radio and press adverts, TV fillers and poster campaigns, and providing information. To those at risk, those affected, and those who are survivors.

The British government, said the state minister for home, Baroness Scotland QC, is determined to protect young people’s “right to choose” their spouses. A determination backed by the state minister for foreign office Lord Triesman’s assurance that “help is available” for its victims.

And so it was. Humayra Abedin, 32 year old Bangladeshi and a London-based doctor, was told her mother was very ill. She returned to her parents home in Dhaka in August 2008 only to be locked in a room, have her passport, ticket and other documents taken away. Before her cell phone was taken, Abedin managed to send text messages, much later, secret e-mail letters, to people in Britain seeking help. On August 13, she was forcibly taken to a psychiatric clinic, held and medicated against her will for nearly three months.

A court injunction issued in Britain was soon followed by a Bangladeshi court order. It instructed her parents to let her return to England if she so wished. She was escorted to the British High Commission, they arranged her return. Back in London, the British High Court issued an order preventing her from being removed from Britain without her consent. She had been forced to marry a man of her parents choice said her lawyer, seeking its annulment as Abedin is a UK resident. Marriage without consent, declared High Court Judge Paul Coleridge in his ruling, was “a complete aberration of the whole concept of marriage in a civilised society.”

The British High Commission in Dhaka had been just as prompt several months earlier when 19 year old Nasrin Begum, a British citizen, had telephoned the British consular office in Sylhet. About to be forced into marriage, Nasrin had “begged” the consulate staff to intervene. And that they did, aided by Bangladeshi police. Forced marriage rescues, says Toafiq Wahab, head of consular services, can be “very challenging.” According to a British High Commision spokesperson in Dhaka, between April 2007 and March 2008, the embassy staff had provided assistance in 56 such cases. But he added, we think there are “more out there.”

The official website for the British High Commission in Dhaka has a Help for British Nationals page. Relatives and friends of those unfortunate enough to be detained or imprisoned, are provided information about local prison conditions, the local legal system. Subject to prison approval, the HC even passes on money sent to buy “prison comforts.” For victims of crime, the HC provides much more: a list of local lawyers, interpreters, help in contacting a local doctor, and, in very exceptional cases, a loan from public funds. For those who have lost their passports, emergency travel documents, on occasions, even a passport. The website displays a customer feedback form inviting viewers to contribute ideas for improving their services.

I wonder how Jamil Rahman would have filled it.

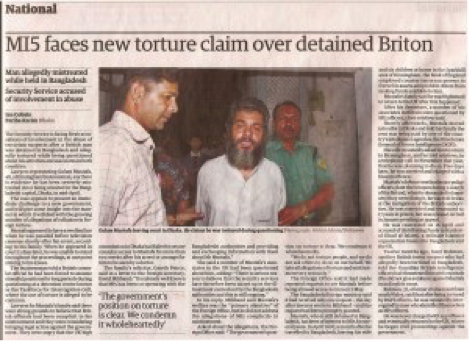

Rahman, 31, a former civil servant from south Wales, settled in Bangladesh in 2005 after marrying a woman from Sylhet. On 1 December 2005, says Rahman, police came to his wife’s family home to take him away. Two men, wearing balaclava masks towered over the police, peered at him through the slits and nodded their heads. Rahman and his wife were taken to the DGFI (Directorate General of Forces Intelligence) headquarters, and held in separate cells. He was stripped naked and beaten. He was told that his wife would be raped and murdered, that her body would be burned. He agreed to confess to a number of terrorist offences, to being the mastermind of the July 2005 underground and bus bombings in London. Released nearly three weeks later — after receiving strict instructions that he should not tell anyone of his experiences, nor contact any lawyers, or members of the media, or the British High Commission in Dhaka — he was frequently summoned for interrogations and repeated beatings for a period of more than two years.

Rahman alleges, two well-spoken Britons, who said they were MI5 officers, that their names were Liam and Andrew, would be present during the interrogations, only to leave the room when he was tortured. When he told them of his torture, of being forced to make false confessions, “help” was not forthcoming. Instead they would leave the room, they “needed a break.” Andrew reportedly added, “They haven’t done a very good job on you.” He would be beaten, extreme pressure exerted on his testicles, threatened that his wife would be raped. After the questioning resumed, Andrew reportedly said, “That’s good, you’ve learned your lesson.” Rahman was shown maps, instructed to copy these on to pieces of paper, which were taken away by the MI5 officers. He was shown hundreds of photographs, including surveillance pictures of UK friends, and asked to identify them. If he did not cooperate, MI5 officials would leave the room, the beating would resume. Senior DGFI agents would utter words of caution. His head should not be marked. His bones should not be broken.

“We are not torturing you, are we?” MI5 officers asked Rahman during many an interrogation session. Once, says Rahman, he was told to repeat `no’ in a louder voice. All sessions were recorded. During this period, he was also questioned by three men who said they belonged to Scotland Yard, and an American woman named Mary. His passport, says Rahman, withheld by officials of the High Commission, was returned two and a half years later. In other words, it had been withheld by the very HC that prides itself on “rescuing” British nationals from emotional and physical abuse. Abuses, obviously, are only those that conform to Britain’s image of itself as civilised.

After Rahman’s return to UK in May 2008, he was not questioned by the police nor was there any attempt to arrest him — largely assumed to be indications of innocence. His wife and son joined him a year later, and soon after, he embarked on legal proceedings, filing a damages claim against home secretary Jacqui Smith alleging that she was complicit in assault, unlawful arrest, false imprisonment and breaches of human rights legislation.

His case is one of the latest in a growing number of cases — 29, at last count — in which British intelligence services have been accused of colluding in the torture of British nationals and residents: Rangzieb Ahmed, Salahuddin Amin, Zeeshan Siddiqui, Rashid Rauf by the ISI, Binyam Mohamed in Morocco, Alam Ghafoor in Dubai, and Azhar Khan in Egypt. Rahman’s case provides the clearest indication so far, of torture outsourced.

Not to be outdone by the current public debate in America on whether it condones torture, the British too, seem to be catching up with increasing calls for an independent enquiry into allegations of MI5 complicity. Contradictions appear as the UK foreign minister David Miliband keeps mouthing, “Torture is abhorrent. Britain never supports or condones it” while simultaneously insisting that the interrogation policy at the heart of the allegations should not be made public (June 2009). Nor is the court injunction (February 2008) gagging Ben Griffin, an ex-SAS trooper, who had revealed extensive British collaboration with US rendition and torture, removed.

And what about us, at the insourced end? A Bangladeshi intelligence officer reportedly told Rahman, they were “only doing this for the British.” This seems to be well borne out by what is known. But who authorised it? Was a Memorandum of Understanding signed? Rahman’s two year long ordeal began during the BNP-Jamaat coalition rule and continued into the Fakhruddin-led emergency period. Two governments needing to be held accountable. I would include the current one as well as I read the UK state minister for security and counter-terorism, Lord West’s recent speech in Dhaka, “we have worked to build the capacity of Bangladeshi agencies involved in counter-terrorism work..” (strange, but Lord West?s statement is also no longer available on the British High Commission?s website) Is capacity-building a polite euphemism for out-sourced torture? Is there something sinister behind his words, “UK could further assist Bangladeshi law enforcement counter-parts in improving their capabilities.” Does it mean more out-sourcing? Support from the metropole for the culture of impunity that protects our home-grown torturers, and `crossfire’ killers?

There are more victims of forced marriages out there, the HC spokesperson had said. I’m sure. But are there more Rahmans as well?

New Age, July 20, 2009

One thought on “On Forced Marriage, and Insourced Torture”