Belonging: A book by Munem Wasif

Preface by Christian Caujolle

It only takes a single glance to recognize a classic. The confirmation can be seen here, in this direct, forthright photography ? the same quality that came through in the series devoted to ?Salty Tears?, in which Munem Wasif examined, documented and questioned the situation regarding water in his country, Bangladesh. Classic by choice, starting with the choice of black and white, whose relative distancing from reality demands exacting precision in the composition. Arising, as always in photography, from a succession of rejections, eliminations and decisions, this choice precludes the picturesque quality that too often prevails when lands and peoples are viewed through the prism of exoticism. But black and white, while it places the photographer within a documentary tradition long associated with journalism, obliges him to go beyond merely transposing a visual record of the world. He must take a position, and he does, deliberately and consistently.

The first element of this positioning is the choice of framing, clear and precise, defining the space allotted to the image. This generates a rectangle in which the eye can proceed from one detail to another, to connect them and give meaning to them, while ridding the delineated scene of dross so that nothing extraneous can disrupt its comprehension. This framework, then, breathes with a natural wonder, expanding and reducing the field of vision, affirming that the photographer?s physical point of view is an explicit attitude towards the world. He can then select one part of a visual agglomeration, to reveal as the central element a sinuous network of necks and crops of unplucked white birds, or, from further back, behind a splintered window, a horse-drawn cart making its way through a crowd. At the same time, the framing is an exercise that, here, recalls classics in the vein of Cartier-Bresson in the way that it imposes a geometrical form and embarks on an investigation of frontality and the slightly elevated view. One of the most telling examples is given in a striking view of the river: a cluster of long, narrow-bodied boats fans out in the centre of the image while, in the foreground, oblivious to the photographer, a barber pursues his delicate task. This rightness of this image lies in its distance from the things it portrays, its distancing of the space, and its capacity to stratify its different levels without resorting to optical artifice for their separation and organization. This photo inevitably evokes one of Wasif?s earlier works in which a boat lies aground on the cracked earth, bearing silent but poignant witness to the extent of the ecological devastation in Bangladesh. This choice of position, seeking out a precise distance, non-formalist despite the exacting organization of the shapes, this internal structuring of the image that cultivates a much more subtle complexity than first meets the eye, is ultimately not so classic after all. Here we have a photographer who knows and obviously admires his classics, who learns from them but who devises his own visual grammar to serve as the basis for an exploration that, as we shall see, is not eminently classic.

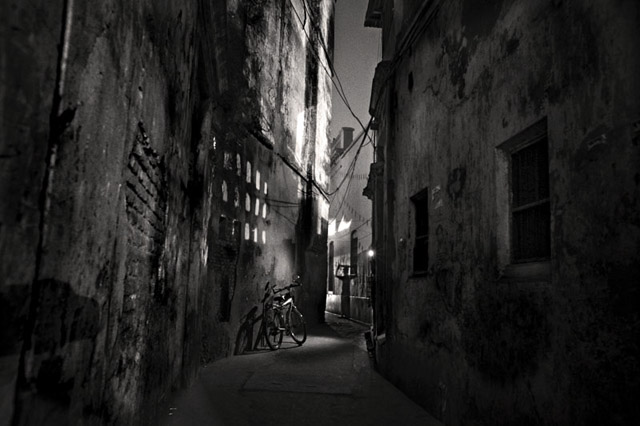

At this point, when we find ourselves immediately intrigued by the ingenious, masterly form, it should be pointed out that not all black and white is equal. Within a practice that seems to function on a simple binary realm, many are in fact working in grey ? or rather greys, with their relative and complementary values. Munem Wasif has chosen a sharp, powerful kind of contrast, with characteristic deep shades of black that he is able to adapt and make germane to the subject of his work. He cultivates a decidedly distinctive chromatic quality of black and white, at once taut and supple, always elegant, understated, but in which one perceives muted tones stirring up the innermost depths. Although they have meaning, the aesthetic, language and formal choices take on validity only through what they enable ? through that moment when, having conceptualized and assimilated them, making them his own, the photographer wields them as a tool of expression, completely forgetting how he developed them originally. Thus we find ourselves transported to Old Dhaka. This, once again, is a choice. The city in which Wasif guides us ? and sets us loose ? is one of those densely populated megalopolises peculiar to Asia, nothing like the small town of Comilla, where as a boy he dreamed of becoming, contrary to his father?s wishes, a cricket star or a pilot, or perhaps a photographer. It was in Dhaka that Wasif?s studies at Pathshala, the remarkable photography school founded by Shahidul Alam in 1998 and the alma mater of a unique generation of young documentary photographers, changed his life and reinforced his choices. He would be a photographer. He then set himself the goal, while remaining perfectly in line with the classical heritage, of portraying the people of his country, offering insights into their daily lives, their modesty, their traditions and the structures of their society, and putting the related social issues into perspective. Humanist, in other words, but not in the nearly cloying sense that came to be associated with the French photographic movement of the 1950s, which did indeed take an interest in people and their condition, but too often resorted to a form of facile ?poetry? whose anecdotal foundations undermined its ability to engage the viewer. Wasif, in contrast, is humanist in his commitment and his choices, most importantly that of intently observing the world around him rather than deluding himself that excellence can only be found elsewhere, and that one must travel far to unearth worthy ?subjects?.

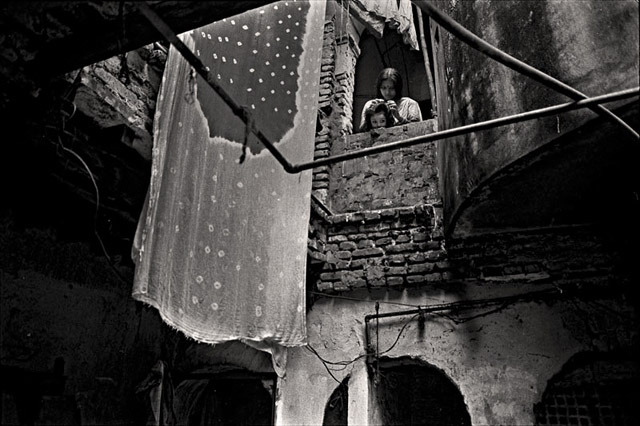

Choosing Old Dhaka is also characteristic of this approach. It means bypassing the modern city in order to plunge, in the true sense of the term, into the heart of the capital, into a history, an all-permeating past, an architecture scarred by age, run-down but still imposing, there to be carried along, apparently at random, by the desire for discovery and interactions: with sources of light ? and contrast ? with forms, with the streets and their crowds of passers-by, from which emerge faces and gestures, as well as interiors. In these visits to families, in this gift we are offered of being admitted into others? private lives without being transformed into voyeurs, we see through the eye of a photographer of raw reality, and realize how precious that is. It is at this point, when there is no temptation of exoticism, that the artist can elevate the local to the universal, making us perceive the extent to which we as humans, beyond any differences of race or religion, all share feelings, affection, love and emotions.

By day and by night, near and around his home (this is where he used to live), Munem Wasif captures ?his? city with the clearly predicated desire to ?find what people do not see in the most mundane of everyday routines?. It?s a true photographic challenge to seek out the things that we do not or no longer see, or that are so fleeting that we cannot absorb their details, things that strike us and yet elude us. Indeed, the impetus behind the very invention of photography arose from the desire to preserve the vision of these ephemeral shadows. And what don?t we see? Gestures that engage in a dialogue and redefine the space in an ever-changing ballet, transparency, a sudden glint that highlights the bridge of a nose or the whiteness of an old woman?s hair, an apparition in a window recess, a tangle of electrical wires that provide a diagonal demarcation or a handhold for a monkey, a ghostly dog that becomes nearly translucent, a fire in the middle of the street, burning a hole into the deep night, animals, faces, people, gestures and more gestures, from affinity to vengeful malice. And, everywhere, the force of light, the light that unveils the world. Light, because without it there would be no day, no night, no photography.

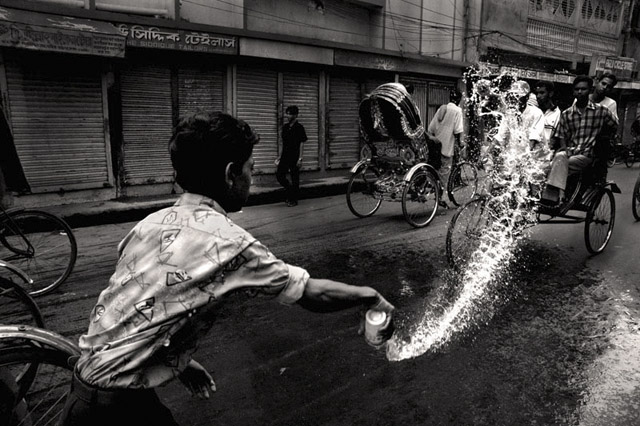

The force of light is also a source of illusion and mystery. It purports to illuminate the world, and indeed it does, but without clarifying it. It transforms the world in relation to the human eye. And when the photographer experiences it and succeeds in capturing it, he can leave us there, outsiders by definition, confronted with the reality of the visual impact but also the utter incomprehensibility of the earthly reality when, for example, a little girl fans out the skirt of her fairy-princess dress on the steps of a languishing palace, when the liquid spurting from a drink can becomes a white plume shot through the air, in defiance of an oncoming rickshaw and the force of gravity, or when a child in the street hides his face, making it a riddle, behind strands of barbed wire whose rusted surface seems nearly palpable.

In fact, these exceptional visual instants are nothing more than a reflection of the photographer?s sensibility. As though by magic, he finds an echo to what he feels in what he sees. Casting his eye over his surroundings like a net, he seems to capture what exists within himself, projecting onto the world as much as he receives from it. In so doing, he quells a part of the chaos of the world, giving structure and intelligibility to what would have looked to us like disarray. And all this just at the next street corner, with no apparent effort, as natural as breathing. Because he has decided to share his experience. He then comes up against an eternal issue for the documentary photographer: the question of narrative. His images fit together harmoniously, but he does not tell a story in the manner of his predecessors, whose work he has no doubt studied well, starting from a premise and proceeding toward a conclusion. Indeed, there is no beginning and no end, but rather a succession of images that lead us, guided by the given viewpoint, along a central visual axis defined by the framing, from which emerge branches that collide and break off, forcing us to switch to another offshoot. As in any tree structure, we can jump from branch to branch, lingering, interweaving disparate threads, reinventing a story that isn?t there but nonetheless has the freedom to exist. In this tension between rigidity and flexibility, in the narrative as in the frame, Wasif establishes himself as an heir to the classics ? a creator of classics in his own right, and in his own manner.

It is neither spectacular nor characteristic, but one particular image seems to me, beyond all that it offers us visually, to embody a point of view: a nearly deserted movie theatre, in which we can just make out the old-world architecture, with decorative columns under a ceiling worn by time and damp, and at the front of the room a completely blank screen. A moment of expectation for the audience, but a moment of action for the light that caresses and lacquers the seatbacks, delineating the space, a long exposure encapsulating, in a single ageless image, a pure revelation. Within this muted rectangle encasing a brightly luminous rectangle, like a disjointed metaphor, not at all conceptual but singularly affecting, there lies the worldview of a young man who wants only to come closer to the things he finds in the world, to bring them closer to use, to arouse emotion like music from the heart.

By Christian Caujolle

Photos and texts by Munem wasif

Preface by Christian Caujolle

Design by Nelly Riedel

Publisher: Cl?mentine de la F?ronni?re

160 pages, 69 pictures

Size 16.8 x 21.8 cm

Binding: Hard cover, printed on Cialux

Language of text: English and French

Year published: 2013

Price: 36 euro

All the picture of Old Dhaka by Munem Wasif are really great. He has been able to capture the essence of the perfectly and choosing the black and white has also added the more dram and reality in these images. Undoubtedly Munem is a great photographer !