rahnuma ahmed

I

Millions watched the wedding of Britain’s Prince Harry and former American actress Meghan Markle on television the world over. While many heralded it for demonstrating ‘how Britain has become more egalitarian and racially mixed‘ and lauded the ”Meghan effect‘ on black Britons,’ others rejoiced at the wedding ceremony for having been ‘a rousing celebration of blackness,’ and still others hoped that the ‘spirit of Harry and Meghan… [would] revitalise our divided nation,’ that prince Harry’s choice of spouse would ‘[initiate] real change in UK race relations.’

Meghan Markle – now Duchess of Sussex, with her own Royal Coat of Arms – is the daughter of a white American father and an African-American mother, her parents divorced when Meghan was 6, and she was raised singly by her mother.

While it is true that Prince Harry’s elder brother Prince William married a ‘commoner,’ namely, Kate Middleton (albeit, her parents are millionaires), Ms. Markle’s credentials are undoubtedly far more ‘radical.’ As Paul Mitchell notes, she was brought up as a Catholic, divorced from a Jewish man, agreed to a confirmation in the Church of England out of love for ‘her man,’ is a genuine celebrity, and a self-proclaimed feminist. Markle’s words, ‘I am proud to be a woman and a feminist,’ uttered at a United Nations conference on International Women’s Day 2015, has been highlighted on her own page on the palace website. She has done charitable and humanitarian work as a United Nations ambassador opposing gender inequality and offering support to refugees, has visited Rwanda, has come to neighbouring India to offer support to women and girls living in slum communities, and is also the author of a ‘powerful essay’ published in Time last year on the need to combat menstrual stigma.

Suhani Jalota, founder of the Mumbai charity Myna Mahila, which provides access to menstrual hygiene education and affordable sanitary products for women, told the Guardian, ‘She really knows her stuff (about the cause). She’s not in it just because it’s trendy but really because it matters.’

Kate Robertson, co-founder of One Young World told People magazine, Ms. Markle ‘more than held her own’ as a Counsellor at the One Young World summit held in Ottawa, Canada in 2017. Markle herself spoke enthusiastically of the summit, of how young people from all over the world are working for change by ‘speaking out against human rights violations, environmental crises, gender equality issues, discrimination and injustice.’

Prince Harry has been reinvented, writes Mitchell, from wearing a Nazi uniform to a ‘colonials and natives’ fancy dress party and calling one of his fellow Sandhurst cadets ‘our little Paki friend’ more than a decade ago to being a ‘global charity ambassador’ who champions wounded and disabled soldiers, mentors young people and devotes himself to saving the wildlife of Africa.

Hadley Freeman views Harry’s coming into his own differently. When Princess Diana’s funeral took place, Freeman herself had only been 19, and she writes about the heartbreaking sight of the ‘little 12-year-old boy in the too-large suit walking in his mother’s funeral procession, stared at by a billion strangers…head bent, not daring to look up.’

But now, with his marriage to Markle, despite the Markles family ‘debacle’ (her father and half-siblings ‘American craving for celebrity’) positive changes are being ushered in: English coldness is giving way to American demonstrativeness (warm, friendly, ‘I’m American. I hug,’ given to expressing an occasional opinion, Bishop Michael Curry’s passionate sermon at their wedding ceremony on slavery, civil rights and a Christian ‘revolution’ founded on love), Harry is no longer that ‘sad and lost little boy’ but ‘such a happy man.’ Leading Freeman to write, although the monarchy is ’embarassing’ as an institution, Diana’s boys aren’t, ‘thanks to Markle.’

And to conclude, ‘What the royals needed all along was an American.’

II

The British media’s coverage of the royal event bordered on the hysterical. ‘Saturation reporting‘ on the wedding day was followed by the Daily Mail bringing out a ‘sumptuous 32-page souvenir photo album’ and ten national newspapers devoting a total of 282 pages to the topic, the day after the wedding.

But not a single national newspaper mentioned the opening of the government inquiry into the Grenfell Tower fire, due to open on Monday (two days after the wedding), on its front page.

The wedding ceremony, which was hailed for its ‘inclusivity’ and ‘diversity’ was nothing but ‘a gathering of the rich and powerful.’ The personal wealth of the six hundred guests who were invited to the Windsor Castle ceremony, is estimated to be $16-21 billion. I quote Thomas Scripps,

‘The Queen’s wealth is roughly $500 million, followed by Prince Charles ($100 million), Princes William and Harry ($40 million each), Prince Philip ($30 million) and the Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton ($10 million). Joining with and often outstripping the British monarchs were Markle’s fellow celebrity ‘royalty,’ including Oprah Winfrey ($2.8 billion), George Clooney ($500 million), David and Victoria Beckham ($450 million and $300 million), Elton John ($450 million) and Serena Williams ($150 million). Representing the moneyed heights of politics, finance and property were former Prime Minister John Major ($50 million), hedge fund manager James Matthews ($2 billion) and the owner of substantial swathes of London’s Mayfair, Hugh Grosvenor ($9.5 billion).’

According to media reports, the wedding cost an estimated £32 million, 94% of which was borne by the taxpayer (£30 million). Ms. Markle’s ‘slender and sleek’ wedding dress (Givenchy), with a 16-foot cathedral-length wedding veil with hand-embroidered flora and fauna from each of the 53 countries that make up the Commonwealth, cost £400,000; the ‘not traditional’ lemon and elderflower wedding cake cost £50,000; 16,000 glasses of champagne and 23,000 canapes were reportedly served to the 200 special guests invited to the after-wedding party.

Fire broke out in the 24-storey Grenfell Tower, a block of public housing flats that housed 600 people, belonging mainly to the working class and ethnic minorities, on June 14, 2017. At least 72 people died.

The Tower lies in the wealthiest locality, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, the residents of Grenfell Tower lived in the cheapest accommodation in the borough. It was refurbished from 2014-2016, cladding was added presumably to make the outside look attractive but it was combustible (plastic-filled aluminium panels and synthetic insulation),

acting as ‘an accelerant [which] turned a kitchen fire in Grenfell Tower into a raging inferno.’

The Hackitt inquiry has refused to recommend that flammable cladding be banned, while the government too, continues to stonewall demands for its ban.

Prior to the royal wedding, Simon Dudley, Conservative Party council leader, tweeted to Thames Valley police to take measures against ‘an epidemic of rough sleeping and vagrancy in Windsor,’ and to ‘focus on dealing with this before the #RoyalWedding.’

After the wedding, Prince Harry and his newly-wedded wife returned to his Nottingham cottage on the grounds of Kensington Palace, a complex which enjoyed a spectacular £12 million makeover several years ago.

III

But no one mentioned ‘wedding massacres’ either.

The only mention of drone attacks that I came across in the media brouhaha over the royal wedding was Freeman’s flippant remark, for the Palace to think that the Markles’ lack of etiquette and craving for publicity could be held back by British notions of decorum was like ‘sending gentlemen on horseback to do battle in drone warfare.’

Nowhere near the Murdoch-owned New York Post’s headline more than a decade ago, ‘Bride and Boom!,’ written smirkingly with reference to a caravan of vehicles that was eviscerated by a US drone attack on a wedding procession in Yemen. According to one report, ‘Scorched vehicles and body parts were left scattered on the road.’

Erika Eichelberger of TomDispatch has chronicled seven wedding massacres that took place between 2001-2012. These are:

December 29, 2001, Paktia Province, Afghanistan: more than 100 revelers died after an attack by B-52 and B-1B bombers.

May 17, 2002, Khost Province, Afghanistan: at least 10 Afghans in a wedding celebration die when US helicopters and planes attack a village.

July 1, 2002, Oruzgan Province, Afghanistan: at least 30, possibly 40, celebrants die when attacked by a B-52 bomber and an AC-130 helicopter.

May 20, 2004, Mukaradeeb, Iraq: at least 42 dead, including ’27 members of the family hosting the wedding ceremony, their wedding guests, and even the band of musicians hired to play at the ceremony in an attack by American jets.

July 6, 2008, Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan: at least 47 dead, 39 of them women and children including the bride, among a party escorting the bride to the groom’s house.

August 2008, Laghman province, Afghanistan: 16 killed, including 12 members of the family hosting the wedding, in an attack by American bombers.

June 8, 2012, Logar Province, Afghanistan: 18 killed, half of them children, when Taliban fighters take shelter amid a wedding party. This was perhaps the only case among the eight wedding incidents in which the United States offered an apology.

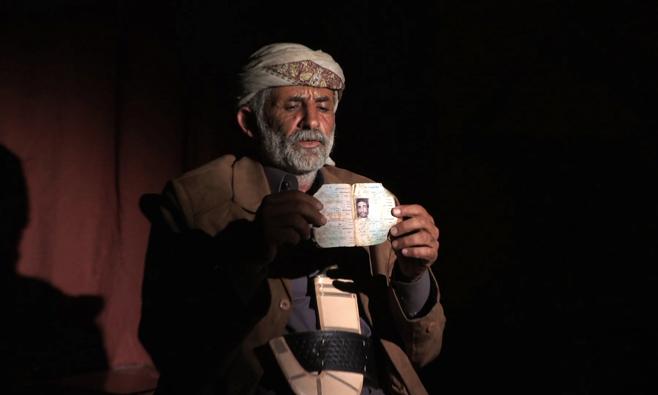

To add another one to Eichelberger’s list, on December 12, 2013, a wedding procession of Abdallah Mabkhut al-Ameri, his new wife and about 60 of their friends and family, travelling outside the city of Rada’a, Yemen, were hit by four Hellfire missiles, killing 10 persons including the groom’s son from his previous marriage, and injuring 24.

But there have been many more, right down to recent times.

According to a 2010 report of a UN human rights special rapporteur, drone attacks violate International Human Rights Law, and International Humanitarian Law. According to Amnesty International, US drone strikes could be classed as war crimes. Pakistan – one of the 53 Commonwealth countries to have been represented by a hand-embroidered flower on Ms. Markle’s veil and had ‘journeyed up the aisle’ with her – has raised the issue of ‘illegal’ drone strikes at the UN Human Rights Council; according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, US drone strikes in Pakistan from 2004-2017 number 429, the total number of persons killed range from 2514-4023, of whom civilians are 424-969, and children 172-207.

A 50-page report of Reprieve charity, released on 9 April 2016, revealed Britain’s involvement in helping draw up extra-judicial kill lists to assassinate the world’s most wanted terrorists and drug smugglers in foreign countries. The UK has been ‘a key long-standing partner in America’s shoot to kill policy in Afghanistan and Pakistan,’ and although the top secret list has been in existence for years, and continually revised, Britain’s contribution has never been sanctioned by Parliament. The two agencies involved are: electronic eavesdropping organisation GCHQ, and the Serious and Organised Crime Agency (SOCA), rebranded as the National Crime Agency.

An innocent Afghan family was wiped out in a missile strike after one of the men on the kill list was mistaken for being a Taliban on September 2, 2010 near their family home in Takhar Province. Habib Rahman, an Afghan bank executive, said his father-in-law Zabet Amanullah, two uncles and two brothers Faiz and Atiqullah, had been campaigning for parliamentary elections and were driving in a convoy, when the US-led air strike killed them, and five others. ‘The Government had promised to support those who supported democracy. I never thought that they would be killed by the Americans or British.’

Rahman’s surviving brother had called to say, ‘I found Atiqullah’s leg, his hand. I found Zabet’s body.’ One of his uncles Miraj, was later found ‘under some soil. He was wounded and after a few minutes, he died.’

Clive Stafford Smith, Reprieve’s director and the lead author of the report said, ‘it’s very distressing [that] Britain, which abolished the death penalty 51 years ago, now seems to believe in conducting executions without trials.’

‘There has got to be a serious inquiry,’ Smith added, ‘and the Government has to come clean. We keep getting into bed with America in violating human rights, as with Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib. They justify it as making Britain safer – but the reverse is always true.’

Why does the TV media marginalise news of drone attacks? In reply, Michael Brooks of the Majority Report had said, ‘[I think] we need to broaden our empathy, we need to think much more seriously about what’s happening in other parts of the world, obviously, particularly if it’s done in our name and I think…that aspect of kind of projecting outward morally and emotionally but it’s also politically very important, we need to be more sophisticated and engaged in our thinking…’ (‘What if a drone strike hit an American wedding?,’ RT America).

But are celebrities engaged in charitable and humanitarian work likely to do so?

IV

Celebrity forms of global humanitarianism and charity work spearheaded by entertainment ‘stars,’ billionaires and activist NGOs – Bob Geldof, Bono, Angelina Jolie, Madonna, Bill Gates, George Soros, Save Darfur, Medecins Sans Frontieres – is far from being altruistic, writes Ilan Kapoor. Celebrity humanitarianism is most often self-serving, it advances consumerism and corporate capitalism, it rationalises the very global inequality it seeks to redress. It is fundamentally depoliticising; while it appears outwardly open and consensual, it is in fact managed by unaccountable elites.

Celebrity humanitarianism arranges a separation, often between the West and the developing world, contends Lilie Chourialaki; it is best viewed as a communicative structure which rests on ‘a particular conception of politics as pity.’ The celebrity embodies the false promise of individual power as a force of social change, the illusion of a single person fighting against structures of injustice, thereby reducing complex problems of development into ‘soundbite’ politics that carry the logic of a ‘quick fix.’ A noticeable shift has occurred in the UN and among NGOs, ‘grassroots mobilisation’ has given way to ‘elite lobbying’ and a reliance on ‘massive private donations.’

Robert Van Krieken insists that colonialism is not only a historical legacy, but an ongoing relationship between North and South. Celebrity humanitarianism re-actualises Western colonialism, it renders the South ‘merely’ the recipient of the North’s charity, but only in ways that are compatible with the North’s economic interests. The icons of the older colonial culture were the soldier, the merchant or the priest, the new icon of modern colonial culture is the ‘celebrity.’

V

Will the new Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle speak out against human rights violations caused by drone attacks, more so, because as a newly-wedded bride, she can imagine better how horrible it must be to have one’s wedding party bombed, the bride herself, killed? Body parts scattered… To paraphrase a HRW report title, for A Wedding to Become a Funeral?

Will her feminist empathy extend to female victims of drone attacks? To say, six-year old Paliko (same age as Markle’s bridesmaid), who was brought to the hospital still wearing her party dress, whose family members had all been killed when a US air patrol had mistaken traditional gunfire to celebrate Pashtun weddings, as enemy fire?

Most unlikely. For, the murder of civilians is built into the USA’s so-called ‘war on terror’ and, as Binoy Kampark writes, Markle is not there to inflict change upon the institution of monarchy, but to be changed by it.

And, Grenfell Tower will perhaps be too close to home.

Published in New Age, May 28, 2018