Photographs Shahidul Alam

Text Rahnuma Ahmed

It was reported in the papers as suicide. On 10 January 1993 Nurjahan, a woman in her twenties from a struggling peasant household from the Maulvi Bazar district of north-east Bangladesh, was found dead from poisoning at her parents’ house in the village of Chattokchara.

Nurjahan Begum, 7th among 9 daughters, had been married five years before the incident. However, her husband abandoned her and she returned home to live with her parents. Later, her parents arranged another marriage for her, but since polyandry is forbidden by Muslim law, it was necessary to discover whether her first marriage had been properly dissolved. Nujahan’s father consulted the village imam (religious leader), who declared that she was free to marry. However, he revoked this later and claimed that the marriage was illegal because the first still stood. A shalish (village council for settling disputes and trying offending villagers) met to judge whether Nurjahan and any of her family members had broken the law. The shalish found Nujahan guilty of fornication, on the grounds that she was still married to her first husband; after debating the punishment, it decided that 101 pebbles should be thrown at Nurjahan and her second husband.

Pebbles were preferred to stones since the intention, reportedly, was to shame the couple rather than hurt or kill them. Nurjahan’s parents were also to be punished; the shalish decreed that they should be beaten with a broom. Nurjahan was made to stand in a hole that was then filled, half burying her, to receive her punishment. As she did so a member of the shalish approached her and castigated her for the shame she had brought on her family. She was not fit to live and should kill herself. Nurjahan was found dead the next day.

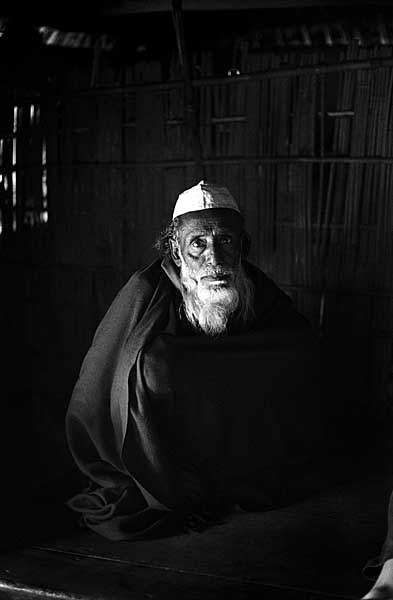

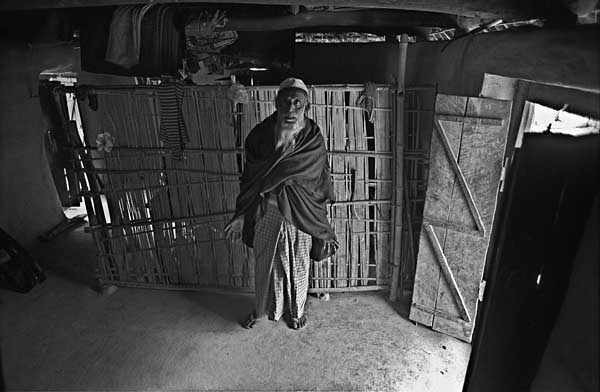

Nurjahan’s father

Nurjahan’s father: “This is where I found my daughter’s body.”

The affair was reported in a local newspaper. A campaign was launched by women’s groups to demand a criminal investigation into the circumstances of the death. Public outrage and the success of the campaign turned it into a landmark case;

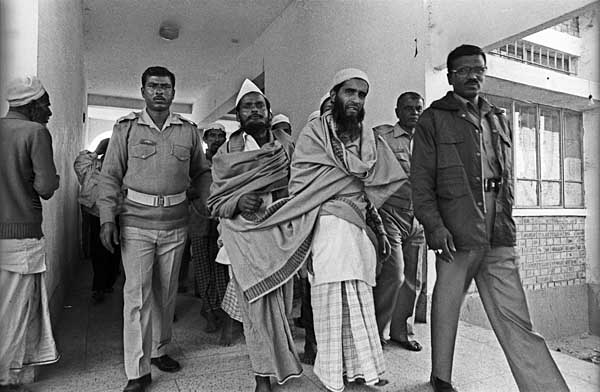

Accused being taken to Moulvibazar court

The accused in Moulvibazar court

proceedings were brought against the imam and the members of the shalish only a year after Nurjahan’s death. He and eight others were subsequently found guilty of abetting the suicide and received the maximum possible penalty of seven years’ hard labour. The village shordar (leader) died of illness while in custody.

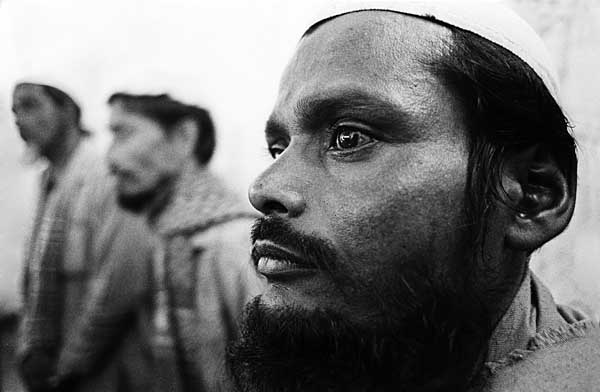

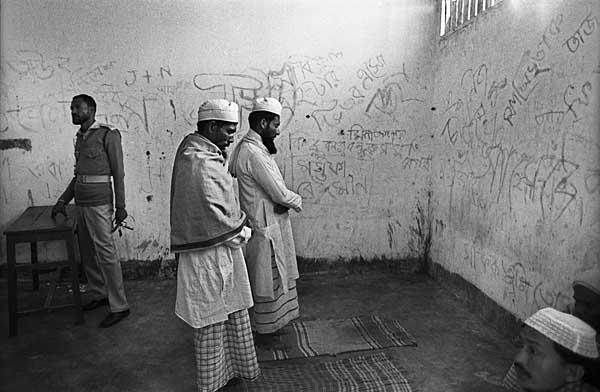

The accused in court jail.

Imam leading prayers in court jail.

Nurjahan’s father believes that his family was made to suffer because of a long-standing enmity between him and the shordar. A female relative of the shordar spoke ill of Nurjahan. “She was a bad woman,” she said. “She would be seen working outside her home.” A rickshaw-puller from Chattokchara came to her defence. “Yes, she worked outside her home. But what other choice did they have?” he argued. “The family is poor.” But he did harbour some doubts. “Why was the wedding held secretly? Why were we not invited?”

Nurjahan’s death has raised many issues for the Bangladeshi women’s movement. Her tragedy has highlighted the manifold forms of women’s subordination within rnarriage, the family and within the community. First, Nurjahan was abandoned by her husband. Then it was the imam who held the knowledge about whether she was free to marry, and he misled her. Finally, it was the members of the shalish, all men, who judged and punished her.

Shalishes have been known to fine and discipline members of the community; at the same time, there are also instances of women disobeying or ignoring and, in some cases, challenging shalish pronouncements. Nujahan’s death has given rise to questions about the sphere of jurisdiction of the shalish, which is a community body with no legal status.

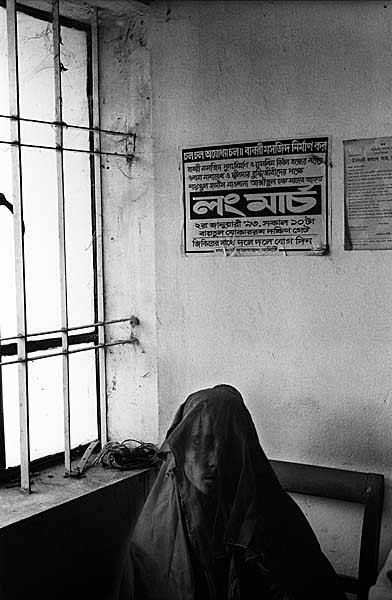

Wife of one of the accused, waiting outside courtroom.

There are few reminders of Nurjahan herself. Of her belongings, a torn corner of a shari, and a shawl she was wearing when she died, have been put aside. Her few remaining clothes were being worn by women in her family. Her only other belongings, a pot and two pans. were being used by her mother.

The family has no photographs. Her grave, like that of the shordar is a small clearing on a hillock near the village, scarcely recognisable as such. The district commissioner promised that the site will be named “Nurjahan tila”.

Nurjahan’s sister at her grave.

The government, in turn, announced that a road would soon be built to Chattokchara. However, in all likelihood, this is probably more significant for visiting journalists and officials, than for her family.

This brought tears to my eyes. I have a 9 month old daughter.

its shows that these type of person should be treated in such a manner that it gives a ample example to this type of others bas…………… ,

A heartbreaking post. It is all too common for ignorant elders and so called sheikhs to decree cultural and tribal justice, and should be rightly punsihed for it. May Allah have mercy on the soul of the poor girl, and ease the suffereing of her family. amin.

Ya Haqq!

Hallo – this reminds me of the wonderful poem by Taslima Nasrin written about this tragedy. It is titled, “Noorjahan” and one key line goes… “Are these stones not striking you?” making the reader feel the event.

-zensufi-

Well what can we say its fully unjust and the sinners got what they desrve. However i dont only blame them i blame my culture and the laws in my country.

I am patern of art and sponser fine artist to paint oil painting that can generate spritual awakening. I am moved by the images and would like to have your permission to use selected images to produce original oil paintings. Is it possible?

Even if the answer is no I do appreciate and love your work.

Ramesh

Mullah Nations..

No surprise there, it will be even worse later on, as rich sylheties around the world are sending money to build more and more madrassa’s. I guess we are aming to make a second Saudi in Bangladesh!!

middle east law in Bangladesh..!!

who is there to blame?

Dear Ramesh,

I don’t know if I ever answered this, but of course you could produce work based on the photographs. Perhaps we could show together sometime.

Best,

Shahidul