by rahnuma ahmed

Why was Irfan killed? Why did they have to kill him, if it was for the money, they had already snatched it away, why kill him? Was it accidental, did he die because a novice, or a brute, hit him on the head too hard? Or did he die because he had resisted, because one of his abductors had grabbed his throat and in the ensuing tussle, squeezed it for a fraction of a second too long?

These questions haunt us, as his killers remain untraced, unknown, even now, a year later.Or, did it not matter to his abductors whether Irfan lived or died, confident in the knowledge that they would go scotfree, as long as their ‘pickings’ were generously shared with those who have the power to administer, and to confer, impunity.

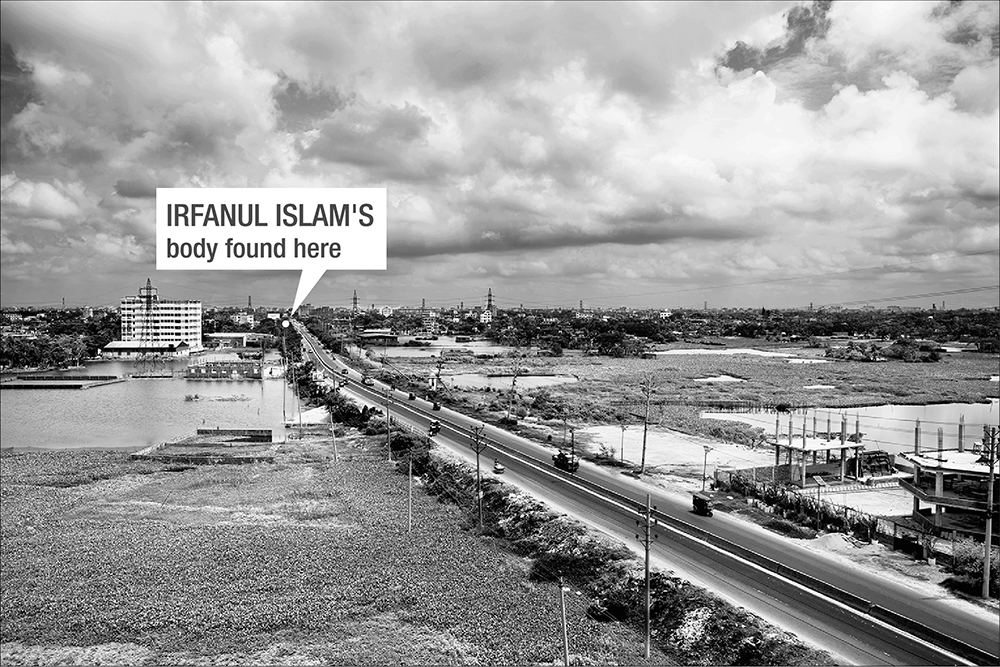

Irfan was picked up on April 2, 2016, his body was found a few hours later, head down, legs jutting out from under overgrown bushes, in a slope off the Dhaka-Narayanganj Link Road, a highway where abductions are known to occur, where bodies are dumped. The media speaks of it as obhoyaronno, a ‘safe haven’ for criminals, eight miles long.

The questions will continue to haunt us until his killers have been caught, until they spill the beans and confess. We will be haunted until his killers have been tried, convicted and punished.

And even after. He was one of the sweetest, gentlest souls I have ever known. Partha Sarkar, a former colleague wrote from Canada, he was so gentle even an enemy would be ashamed at the thought of being his enemy. He wouldn’t, literally, hurt a fly. A disarming smile, childlike innocence.

He had been with Drik for nearly two decades, he was its administrative officer and accountant when he died. The 2nd of April last year was a Saturday morning, DBBL is one of the few banks open on a Saturday, he went alone to its Road 7 branch to cash a cheque, disregarding office rules: never go alone, never go without office transport. But why? We will never know, he had seemed to be in a bit of a hurry, possibly, there were other pressing things. It was probably one of those moments when we tell ourselves, be back in a jiffy, no one will know.

It was a slip-up, it cost him his life.

I was in Drik that day because a couple of weeks ago, I had assigned myself certain tasks (setting up a Trust or Foundation in the name of Drik, pushing ahead plans for the construction of a building which would house both Drik, and its educational institute, Pathshala etc.) to help Shahidul Alam, its managing director, and my partner, tasks that would take several months of dedicated time. We were in a meeting when I heard that Irfan had not returned from the bank, that he was missing.

We rushed to Road 7. We spoke to Nasir Uddin who had driven Irfan to the bank. Nasir said, a traffic policeman had been on the prowl, he had driven off to Road 8, but that hadn’t saved him from getting a parking ticket. They had spoken on the phone, Irfan had said he’d be out shortly, when he didn’t, Nasir went to the bank looking for him. Bank officials said, he had left.

We spoke to bank officials who confirmed the story. Irfan had cashed a cheque for 3,08,000 taka and left. Puzzled, more than alarmed, we went to Dhanmondi thana, they listened sympathetically, only to tell us that the Road 7 DBBL branch was under Kolabagan thana. We went there, filed a general diary, returned to Drik. Irfan’s wife Zohra Akhter, his elder brother Imdadul Islam, and other family members had already arrived.

Zohra was crying helplessly. Was it premonition, had she known? Irfan, I realised later, was probably dead by then. Work at Drik had come to a standstill.

Three search parties were formed, one went toward Hatirjheel, the second, toward Beribadh-Bosila-Gabtoli, and the third, Gabtoli-Ashulia-Tongi-Uttara. By then, friends, acquaintances and well-wishers had begun dropping in, some were concerned at Shahidul being abroad, however, everyone pitched in as best as they could. Since connections matter in Bangladesh, phone calls were made to whichever higher-up whoever could access, Irfan is missing, can you help us?

The search parties returned, they had stopped and asked little crowds of people and passersby every so often, but no, no one had seen or heard anything untoward. Early next morning, on April 3rd, another search party left, this one toward the Demra-Kanchpur-Mawa highway.

None of us had thought of Narayanganj.

We reached the the Dutch-Bangla bank just as doors opened, the officials kindly agreed to show us CCTV footage of the day before. Transfixed, we watched Irfan climb up the the stairs to the bank which is located on the first floor of the building, only to be interrupted by a phone call from Drik. Bad news apa, said Rezaur Rahman, general manager, Drik, they say someone matching Irfan’s description has been found dead in Narayanganj. He was wearing a yellow panjabi and a white pajama.

As we sped towards Narayanganj, I was forced to face the possibility that Irfan was dead. Irfan often wore the yellow panjabi, it was his favorite, and I thought to myself, what is the statistical probability, how many middle-aged men gone missing since yesterday are likely to have been dressed in a yellow panjabi and a white pajama? Not many.

The last time I had gone to Narayanganj was to join in protests against the murder of Tanwir Mohammad Taqi, son of Rafiur Rabbi and Rawnak Rehana (Bulbuli). Taqi, a brilliant student, had only been 17; he had been missing for two days, his body was found by the banks of the Sitalakhya river on March 8, 2013. Rabbi bhai, the convenor of Narayanganj Gonojagoron Mancha, and a writer, had alleged that Narayanganj’s ‘godfather’ Shamim Osman, was behind the killing. Shamim Osman, an Awami League leader, had stood for the 2011 Narayanganj mayoral elections, Rabbi bhai had campaigned for his rival Dr Selina Hayat Ivy, she too, belongs to the Awami League. Shamim Osman had taken his defeat badly.

I hadn’t been to the Narayanganj General Hospital (earlier, Victoria Hospital), or the morgue behind, but I had taken a stack of photographs of Taqi’s body to a forensic doctor in Dhaka, seeking his professional opinion as to whether Taqi’s body bore signs of torture. As I walked into the morgue it felt familiar, may be because of the photos, but it hadn’t prepared me for the sight of Irfan lying dead on the morgue’s trolley.

Imdadul Islam came in, his face crumpled when he saw Irfan. He slowly nodded his head. The identification was over.

Getting official clearance to take Irfan back to Dhaka, getting the coffin made, was a long wait. A local journalist’s tip-off had helped, the police can drag their feet, you won’t reach Dhaka before midnight, don’t you know someone important enough who can call the thana? A dear friend did, I’m grateful to him. He wouldn’t like to be named.

Although we were so many from Drik outside the General Hospital, beside Reza there was Anowarul Azam Rony, Habibul Haque, Mazharul Islam, Prince Mahmud, Zakir Hossain, and of course, Nasir?I felt helplessly alone. I rang singer Amal Akash, a resident of Narayanganj, he came over to the hospital with a couple of friends, they hung around with us for most of the day. Their presence was comforting. As was the thought that Kamal Hossen, Saleh Ahmed and others were holding the fort at Drik.

Irfan had a slight stammer. But we hadn’t known that he stammered only when he spoke Bangla. At the memorial programme organised on April 6th at Drik, attended by scores of grieving friends, Tanvir Murad Topu, head of photography department, Pathshala, startled us with this revelation. Anisur Rahman, teacher at Pathshala (he too, has died; of misdiagnosis), had let Topu into the secret. Primed by Anis who called over Irfan, Topu had asked him something in English. Irfan replied fluently, not the faintest hint of a stutter. When Topu wondered aloud, which language did Irfan struggle in, to save his life? To cry out, to tell his attackers he needed to live for Umam, his 15 year-old son, no, don’t kill me, please, no, his consciousness was slipping fast, was it Bangla, or English??we sat, dumb.

Irfan’s death is not an isolated incident, insisted Saiful Huq Omi, photographer and founder of Counterfoto. He is a shaheed (martyr). In this graveyard-that-is-now-Bangladesh, Irfan will live on for me as Tonu’s brother (Comilla college student Sohagi Jahan Tonu, gang-raped and murdered on March 20, 2016; mother alleges army men were involved, no arrests, no chargesheet yet); he will live on as one of the five killed at Bashkhali (from police firing to quell protests against Chinese-funded coal power plants to be built by S. Alam Group).

Shahidul managed to catch the earliest flight home, in time to attend the protest rally organised by Drik and Pathshala at Raju Bhashkorjo, Dhaka University, on 9th April. Irfan had many qualities, said Shahidul, all marred by one fault. He was not a VIP, nor close to the government, nor to any godfather. Irfan was an ordinary citizen. Ordinary people no longer have the right to walk about freely, to do ordinary things like going to the bank, cashing cheques, returning safely. They do not, it would seem, have the right to live.

Zohra spoke briefly, it was a simple question, of a wife who had loved her husband intensely, ‘who dared to raise his hand on Irfan? Who dared to harm him. I want to see his face.’

We met the OC (officer-in-charge) and the IO (investigating officer) of Kalabagan thana many a times, and talked to them at length. In case of any serious crime, we suspect members of the family first, workplace colleagues next, that is how we proceed, they explained to us patiently. Irfan had no enemies in the family, nor at his workplace. We have made a thorough investigation. He was right, I thought to myself, it had been pretty thorough. I remembered the young guy who had turned up at Irfan’s memorial at Drik, none of us knew him, he had sat in a corner and whispered live updates into his mobile phone.

But because of the media buzz, and because Irfan had worked at Drik, well-known both nationally and internationally, Irfan’s murder was being investigated by four agencies, we were told. One of these decided to pick up Nasir, he was released several hours later, limping badly, and terrified. He’d been threatened, he’d be shot dead if he told anyone or went to the doctor. We got him admitted into a safe-house (hospital) secretly. When I raised the issue with concerned people later, I was told, but surely you want Irfan’s killers to be caught? Yes, of course, I said, but our law enforcing agencies are known to be trigger happy. Surely you can do better than resorting to ‘criminal’ methods to catch criminals?

There was anger, and fear, at Drik, on top of the trauma at losing our beloved colleague, Irfan, and so violently.

I had a niggling thought, one I couldn’t get rid of. According to early press reports, the police suspected Irfan had been murdered by ‘professional’ killers (Prothom Alo, April 5, 2016). Why, what had made them suspicious? A micro yes, he had possibly been picked up in a microbus, and only professional gangs use micros. And then it clicked one day, amidst visits to Narayanganj, to the spot where Irfan’s body had been found, chatting with jhut (garment cloth wastage) godown workers close to where he had been found, to Siddhirganj thana officials, and local journalists. Access to a safe haven, in broad daylight, assurance of a clean getaway, could only be guaranteed in ‘home turf’ of the very powerful. Who else would know that, but professional killers? The CCTV cameras set up by the police on the Link Road are reportedly out of order. When we dropped in at the thana another day to enquire about Irfan’s post-mortem report, the OC barely spoke to us, he was speaking on the phone, he would be attending Shameem Osman’s mother’s chollisha today (Muslim prayer, forty days after death). Local journalists shook their head, it is difficult to get at the bottom of anything here, especially after the prime minister said in parliament, she would stand by the Osman family, ‘I will take care of this family, if necessary.’ (Dhaka Tribune, June 4, 2014).

There have been press reports every 2-3 months or so, reporting Zohra’s anger and Drik’s frustration at the lack of progress. Sudden bursts of activity follow, focused, for unknown reasons, on Drik. Yet again, wanting, a full list of employees, a full list of phone numbers, email addresses. Was anyone else employed then, someone who has since left..? And then, everything dies down, till the next media report.

Joshimuddin Talukdar, senior driver at Drik, had seen Irfan as he was getting into Nasir’s car to go to the bank. Irfan had told him, unusually so, ‘Joshim, apa ke dekhe rakhben’ (Look after apa). These words add to my grief, for I had failed to reciprocate.

Published in New Age, April 2, 2017.

Tags???????????????

Dhaka-Narayanganj Link Road, Drik, Dutch-Bangla bank, Iftekharul Islam Umam, Irfanul Islam, Rafiur Rabbi, Shahidul Alam, Shamim Osman, Tanwir Mohammad Taqi, Zohra Akhter

Identity

Bangladesh

Killings

Rahnuma Ahmed