I’d pretty much perfected the art. I’d go down to the newest library I could find. Become a member as quickly as I could, and armed with my new membership card head straight to section 770, the magical number for photography at UK public libraries. I would take out the full complement of 8 books that I was allowed at any one time. When the lending period was over, they would be replaced by another eight.

I devoured the books, which were mostly monographs, or ones on technique, composition or even special effects. I knew too little about photography, to know how limited my knowledge was. It was many years later, when my partner Rahnuma, gave me a copy of “The Seventh Man” by John Berger, that a new way of looking at photographs opened up. Unknowingly, it was the book “Ways of Seeing” that later opened another window. One that helped me see the world of storytelling. That was when I realised that image making was only a part of the process. Once youtube arrived on the scene, and the television series with the same name entered our consciousness in such a powerful way, his TV series “Ways of Seeing” became my new staple diet. Here was a leftie who could still speak in a language the average person could understand, and that too on a topic such as art. His fascination was neither about the artist nor the artwork itself, but how we responded to it and how it gained new meaning through our interaction. While it was art he was dissecting, it was popular culture he was framing it within.

That there was so much to read in a photograph, beyond the technicalities of shutter speed, aperture and resolution, is something my years of reading section 770 had never revealed. The photographs of Jean Mohr (The Seventh Man), were unlikely to win awards in contests, or fetch high prices in auctions, but Berger’s insights into the situations and the relationships that the photographs embodied, gave them a value way beyond the mechanics of image formation. Berger never undermined the technical or aesthetic merits of a photograph. He simply found far more interesting things to unearth.

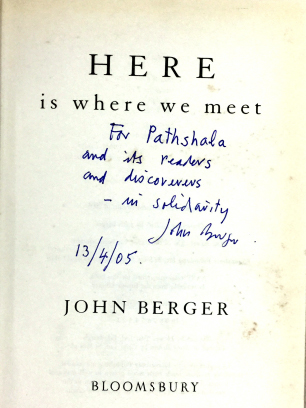

When my film-maker friend Paul Bryers mentioned a book launch by John Berger at the Southbank in London, it got an immediate highlight on my digital calendar. As one might expect, there was a fair crowd, but not the hordes that I had felt one of the leading intellectuals of our time might attract. I wasn’t complaining, as it gave me a chance to talk to the author at greater length and get his book “Here is where we meet” signed for our school of photography.

I didn’t miss the opportunity of inviting him to our festival Chobi Mela. His bellowing laughter might have felt dismissive, had he not quickly confided in me that he hated flying. It was much later that I got to know that even coming to London was something he generally tried to avoid. Preferring instead his retreat in the South of France, in a village, surrounded by a community he knew. In a conversation with Susan Sontag, he refers to this community, reflecting on how, their observations on the characters he created, provided new meaning to his work. Years later, when my own book was coming out, my editor Rosa Maria Falvo and I put together a wish list of people we’d try to get to write the forewords. John Berger, Raghu Rai and Sebastiao Salgado made up our dream team. Raghu and Sebastiao both wrote lovely pieces. John politely declined, mentioning that he was “restricting his ‘outside’ work to a minimum in order to be able to concentrate on a new book.” While I was disappointed at not having a foreword by Berger, that someone nearing ninety was embarking on a new book, was quite inspirational.

The book launch at the Southbank also had a section on another fascinating book. It was a collaboration between John Christie and John Berger that had started curiously, when Berger had written to Christie, ‘just send a colour’. It had been in response to Christie’s question about what their next project might be about. Christie sent across a painted square of cadmium red. The series of letters, notes, drawings and ideas that floated across the English Channel became a scintillating conversation that ended up becoming far more than a discussion on colour. It ranged from cave painting to industrial design. To how artists as varied as Matisse and Klein had used colour. The book “I Send You This Cadmium Red” might have started with that red patch, but embraced the entire spectrum of intellectual pursuit that these two imaginative minds wrestled with. Their conversation was like musicians performing an Indian classical raga, beginning with the alaap, but playing, teasing, each trying to outmaneuver the other and ending with a mutually respectful bow. Much like the sitar player and the tabalchi would duel, weaving in and out, enjoying both the pursuit, but also the other’s dexterity and ability to hang on.

Berger told his stories for a specific audience. While he also wrote novels, he felt there was no intensity in a story that was as intense as the reality that it emanated from. It was life he was writing about, and it was because he believed life was readable to the storyteller, that he chose to become one. He believed experience was shareable and that the storyteller was in a unique position where she was both at the centre and the horizon. While his writing was lucid, powerful and convincing, he was somewhat skeptical of the written form, feeling that most modern novels were in some ways disguised autobiographies.

His choice of living in a village, surrounded by a community he?d come to know, was important, because he needed to know that the stories he told mattered to them. It was them he was writing for, though he did feel that the written story was transportable in a way the oral story wasn’t. While he was writing for a specific audience, he also recognised that through writing, it would reach a bigger audience. Television worked for him, because he felt he got closer to the listener. It had the intimacy of the oral form, but the reach and transportability of text. He saw it as his immediate community, multiplied many times over. When he did write, he wanted his stories to be read, as if they were spoken.

While Berger had never worn his left label on his garb, he had a lifelong commitment to left ideals. Despite dissociating himself from Russia, once it had decided to go nuclear, his politics was evident when he donated half of his earnings from the Booker Prize he won for his novel ‘G’, to the London Black Panther movement. While he saw both art and culture through a political lens, it was his skill as a listener and an observer that gave him his marvelous insight. Never was he going to let art be sacrosanct. Instead, he made it an avenue to understand the cultures that art existed within. Where others saw art as some isolated sublime entity, devoid of politics, Berger found evidence of race, class, gender, sexuality and power and how some artists lived within those power relationships, while others, like him, were busy dismantling them.

Migration had been the theme for “The Seventh Man” and a topic very close to his heart. My new book ‘The Best Years of My Life’ on the same theme, was to make its way to him in France. But the man who taught us that ‘seeing came before words’, and that ‘the relationship between what we see and what we know is never settled’ will be seeing the book from a world we have not yet entered. There too, I am sure, he will find other ways of seeing.

Shahidul Alam

First published in New Age

cadmium. what a thing it is

it deffinitely worth this post.

thank you so much shahidulnews.com