by rahnuma ahmed

Dissent is the highest form of patriotism.

-President Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809)

Patriotism means to stand by the country. It does not mean to stand by the President.

-President Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909)

May we never confuse honest dissent with disloyal subversion.

– President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-1961)

Why remind readers about about dissent being “the highest form of patriotism”? The need to distinguish between “patriotism” and blindly following what the president, or the ruling party `dictates’? Between “honest dissent” and “disloyal subversion”? That too, at the very beginning of my column?

Because, the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, passed by the Parliament on June 30, 2011, approved by the president on July 3, 2011, states, in various provisions added on to Article 7 (my translation):

If anyone undermines the trust, faith or resolve of citizens in the Constitution or any of its provisions, or attempts such an act or conspires to, it will be deemed an act of sedition and the person guilty of this act will be deemed to have committed sedition.

And, for citizens too stupid to have not understood the above, it tucks in these extra bits if any individual

(a) provides assistance to any such act [as described above] or provokes it, or

(b) approves, forgives, supports or follows anyone supporting [such an act] s/he will be deemed guilty of the same misdemeanour [i.e., sedition]

The person convicted under the provision of this article will be awarded the maximum punishment prescribed for other criminal activities under the existing law.

And the “maximum punishment” for sedition, as we know, is death by hanging.

But why quote US presidents? Because the ruling government headed by Sheikh Hasina seems to wholeheartedly believe that the US is a bastion of democracy which furthers democratic endeavours the world over, as evidenced yet again for the umpteenth hundredth time when the visiting US undersecretary of state for political affairs Wendy R Sherman called on the prime minister. Sherman said, the US “wanted to see continued and strengthened democratic process in Bangladesh.” Hasina obliged by responding, “the Awami League ha[s] always fought for democracy” and, is “currently… working [with the US] to strengthen the democratic system” in Bangladesh (New Age, April 6, 2012).

In other words, we gotta have American presidents on our side as we patriotically dissent. As we write on seditious matters.

But there have been other dissenters [seditionists?] to the Fifteenth Amendment, for Dr Sadeka Halim, the information commissioner, has recently said — referring obviously to Article 6(2) of the Constitution which states,

The people of Bangladesh shall be known as Bangalees as a nation and the citizens of Bangladesh shall be known as Bangladeshis.

— that “all the people living in Bangladesh were Bangladeshis and not…Bengalis“. Adding for good measure, “the state had no authority to impose the Bengali identity on people of other ethnicities” (emphases added, New Age, April 6, 2012).

Many others, and they include constitutional experts, jurists, politicians, rights activists etc. criticised the Fifteenth Amendment immediately after it was passed. It was a “despicable offence” for it had dis-empowered the people (constitutional experts Dr Kamal Hossain, Dr Shahdeen Malik). It was “contradictory to fundamental rights” (Supreme Court lawyer and constitution expert Justice Dr T H Khan). It has crossed the limit in “intimidating citizens or cheating them” (Supreme Court Bar Association president Advocate Khandkar Mahbub Hossain).

Others have expressed deep alarm at how, in the name of restoring the spirit of the 1972 Constitution, the ruling Awami League (and its venerable left allies who cast their vote in favour; it passed with a huge margin of 291 to 1 votes) has seemingly paved the way for restoring Baksal, or the one party rule established by the then ruling Awami League government in 1975. For closing down the path of “freedom of expression and… objective, independent, intellectual and constructive criticism of any article of the constitution.” For, “arresting and putting behind the bars all writers, speakers, editors” critical of autocracy and dictatorship.

But my favorite note of dissent to the amendment is the one expressed by Nurul Kabir who, in an obvious reference to what the opposition party chief Khaleda Zia had said, had demurred. “Instead of throwing the constitution into [the] dustbin it should be preserved as an example of poor intellectual exercise and [the] politics of convenience” (New Age, August 6, 2011).

A poor intellectual exercise undoubtedly with regard to many matters, but what concerns me today is Article 6(2), which, by declaring that “the people of Bangladesh shall be known as Bangalees” has most viciously snatched away the ethnic identity of distinct groups of people — Bawm, Biharis, Chakmas, Garos, Khasis, Khumi, Khyang, Lushai, Marmas, Mrus, Pankho, Sak, Santals, Tanchangya, Tipperas, Uchay and many, many more.

Mind-boggling, if not, sheer insanity on the part of the law-makers, particularly so, because the government of Pakistan (against whom we rose up to fight for our independence in 1971) had later introduced a similarly despicably offensive provision in its constitution — undermining trust and faith in the constitution and its amendments to be regarded as seditious.

Intellectual paucity was further demonstrated by no one less than the foreign minister, Dr Dipu Moni when, to justify Article 6(2), she held a meeting with journalists and diplomats at her ministry on July 26, 2011, reading out a statement to clear away alleged “misperceptions” about the nation’s history, its identity, about the “ancient anthropological roots” of Bengalees, about who are the “original inhabitants”, and who are “late settlers” to this land.

The statement says,

Hence, in Bengal, termed as ancient ?banga? and now independent Bangladesh, its original inhabitants or first nations of this soil are the ethnic Bengalees by descent that constitute nearly 99% of Bangladesh?s 150 million people. They have all been original inhabitants of this ancestral land for 4,000 years or more according to archeological proof found in the ?Wari Bateshwar? excavations.

This is precisely what Masood Imran, an archaeologist who teaches at Jahangirnagar University, contests in “Jatiotabadi Rajnitir Bangalittobaad. Oshotto-asroyi Itihash-Rochona Proshonge” (Nationalist Politics and Bengalicism. On fabricated history-writing). His essay is to be published soon in the booklet series Public Nribigyan, of which I’m the editor, which was launched late last year. His essay deals with many issues, most substantively so, but given space constraints, I confine myself to picking on a single strand of his multi-layered work.

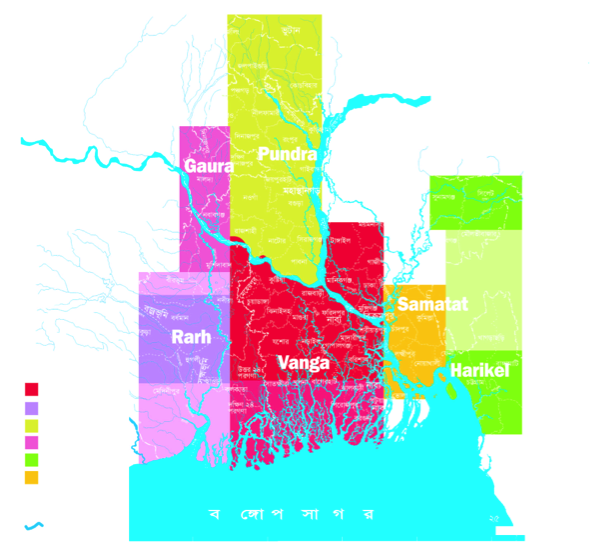

Ancient Banga, says Imran, is not what is now independent Bangladesh. If you look at the map (I’m grateful to Munir, graphic designer, New Age, for having inserted the names of human settlements as are known to have existed here 4,000 and more years ago, in English letters), you will find instead of one “ancient ‘banga'”, several human settlements — Gaura, Pundra, Rarh, Vanga, Samatat, Harikel. A picture that has been pieced together by diligent archaeologists working from fragments of pre-historical records. These settlements had enjoyed their own patterns of habitation and geography. Of material life and forms of rule.

From what I can deduce from the map, which, by the way is speculative, but it is speculation based on available archaeological evidence conforming to the rigors of academic enquiry, none of the human settlements conform to what is “now independent Bangladesh.” There were four human settlements — Vanga, Pundra, Samatat and Harikel — the bulk of which fall in “now independent Bangladesh” but these had also spread outwards into “now” India. Worse still, for the foreign minister that is, Wari Bateshwar (Dipu Moni’s “archeological proof”) was located not in Vanga, but in the unmarked area above Samatat.

Actually, very little is known about our pre-historical times, which is why the two archaeologists A. K. M. Shahnawaz and Masood Imran, authors of Manchitre Banglar Itihash (Bengal’s History in Maps, 2011) have marked out these settlements in blocks/panels which pale off into lighter colors in parts, about which archaeological evidence is thin.

But surely it is better to be cautious than to shoot off one’s mouth? To time-travel backwards and impose present-day territorialities on hapless ancestors who had little foreknowledge of the descendants they would be breeding many moons later? To impose our ethnic identities on others, just because one can command coercive powers of the state?

One would have hoped that the foreign minister, degrees-and-all, would have known better.

—-

Published in New Age, Monday, April 9, 2012.