The Drik Calendar 2019

As things settled, we decided we would continue doing the things we did. That would become part of our resistance. However, the Bangladeshi Jail Code has restrictions on what a prisoner can send out. In my case, it meant a complete firewall.

Resourceful as ever, Rahnuma and Saydia, managed to get a short list of suggested photographs through to me, and I was able to do an edit. Abir Abdullah and Tanzim Wahab were to co-write the introduction. But we had underestimated the power of our brilliant legal team and the sheer doggedness of the local and global campaigners and I was finally granted bail on 15th November. Even that didn’t lead to my release, and after a lot of drama in and out of court, and tension constantly rising outside the jail gate, the political dam burst, leading to my release on the night of the 20th. As we sang our way out of prison, Rahnuma whispered in my ear “you have an intro to write.” No rest for the wicked.

We grow up learning to obey rules. Acceptable behaviour hinges on conformity. Rules have their uses. Basic technique is certainly useful. Mastery over one’s medium is rarely achieved without a great deal of discipline. Behind the glamour and the glitz of celebrity photography lies many hours of relentless graft. Being good requires hard work, and knowing the rules is an essential pre-requisite. So where does a school position itself? How does it encourage creativity? How does one nurture without shielding? Set examples, but avoid cloning? How does one prepare students for mainstream careers while retaining their joy in bucking the trend?

In an educational culture that celebrates textual literacy above all else, the compulsion to understand visuals was itself a radical approach. The idea that in an image-saturated world, we could get by without understanding the primary tool for shaping minds-while bizarre-is understandable. Policy makers after all, are old school, having grown up in the same “sit, heel, beg” environment that has stifled creativity. New ideas rarely emerge from old ways of thinking. It also involved moving into uncharted territory. Bureaucrats are not known for taking risks.

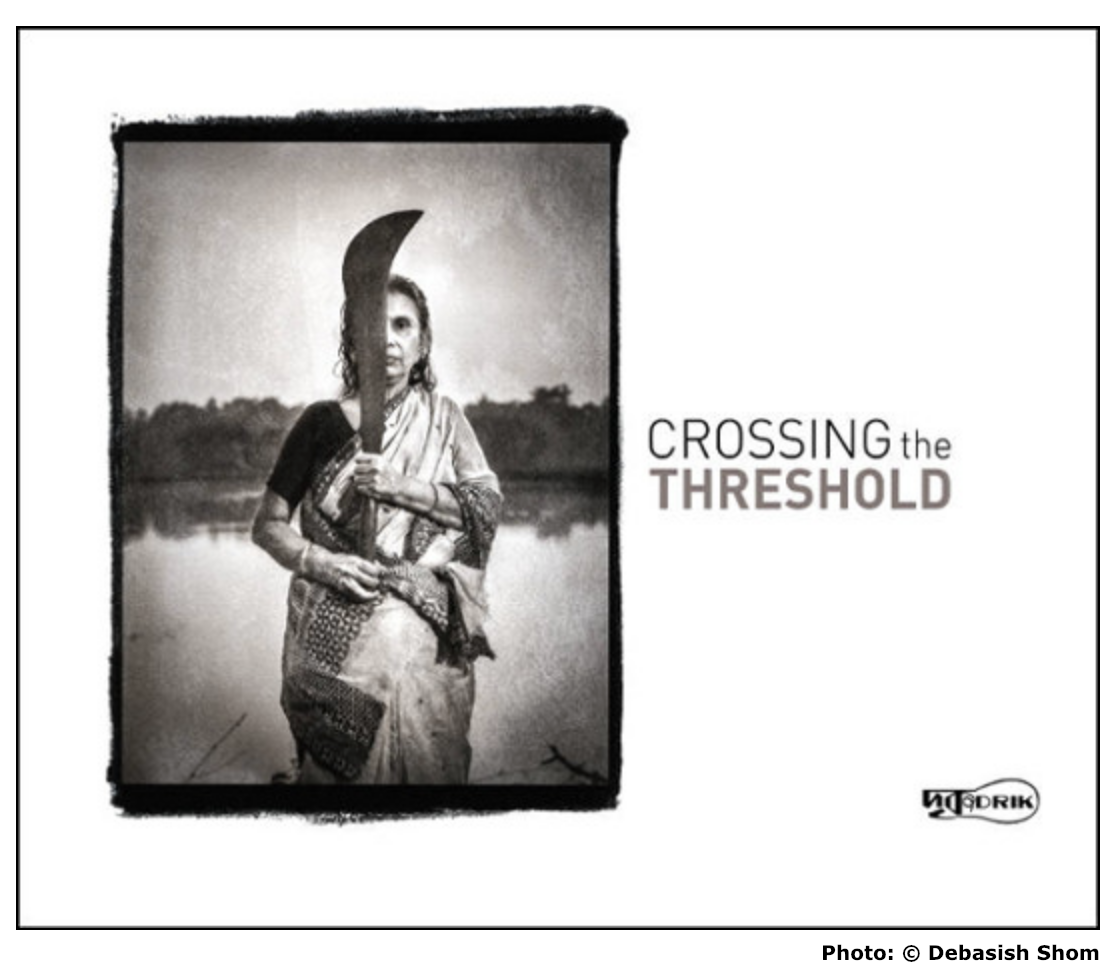

The finest practitioners in the world sat under our mango tree and rapped with students. The students responded, producing strong work that dealt with crucial issues. They had great skills, but lacked the confidence to make mistakes. Their fear of getting it “wrong” was the hurdle we needed to cross. A careful mix of teachers, with diverse approaches to photography, coupled with a conscious effort to encourage experimentation, opened doors to unexplored spaces. It didn’t always lead to “good” work, but the crossing of that threshold led them to a whole new world and many forms of storytelling. As we enter our twentieth year, we find a diversity that is vibrant and has a refreshing unpredictability, which is rare for a school. That combination of excellence, flair and individuality, as opposed to a unified and sanctioned approach has become the hallmark of Pathshala.

It is not simply form that we are talking about. The “why” remains an integral question. The images presented in this calendar deal with complex issues ranging from social inequality, religious intolerance, violence against women, state repression and exodus while also looking at interpersonal relationships, love and desire.

Some approaches are visual, some performative, others are more conceptual. Materiality is explored through found objects and metaphors. The limits of the medium and its inability to record extremes of luminance levels are turned into the essential features of an image. Stolen moments, constructed tropes, collages and photograms straddle the entire gamut of the medium from photojournalism to fine art and every shade in between. The medium is stretched till it screams. But it screams in delight.

Shahidul Alam

Managing Director, Drik

Founder, Pathshala – South Asian Institute of Photography