Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Rahnuma Ahmed

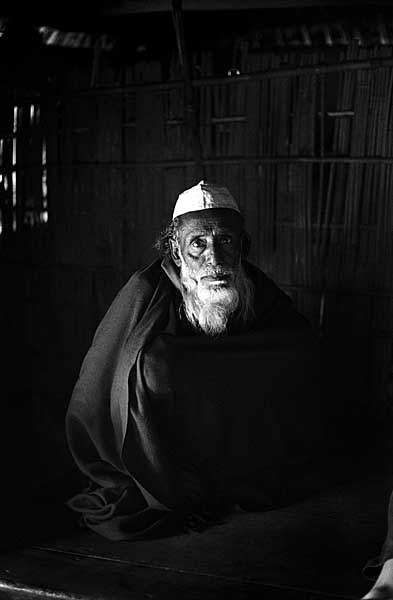

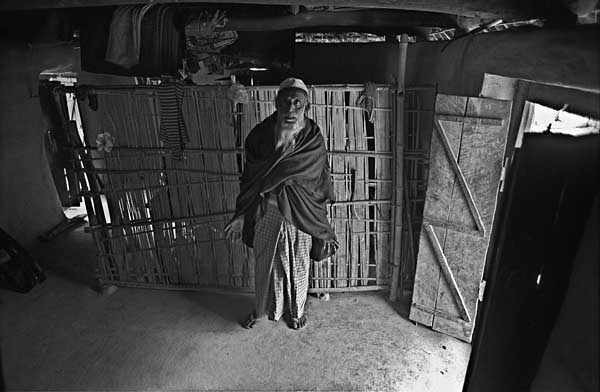

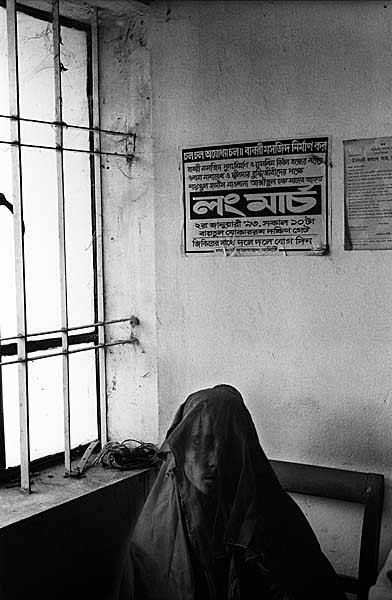

WHENEVER I approach her, I feel numb. I feel speechless. I want to know who she is. But I don?t know who to ask. How to ask.

This photograph has always haunted me. I don?t remember when I first saw it. Probably in a book of war photographs. And later in the Muktijuddho Jadughar, where I have gone many a times with relatives and friends, visiting from abroad.

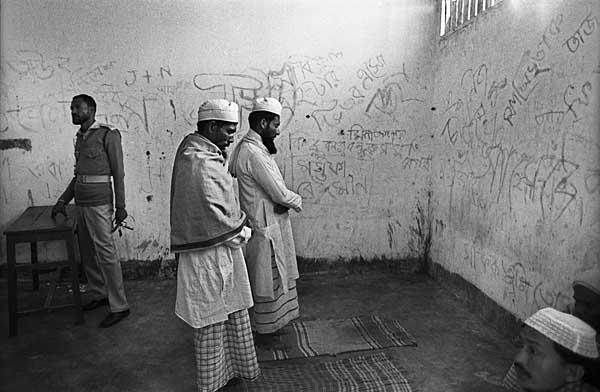

?She was pulled out. Dragged out from the Pakistani army?s bunker,? said Naibuddin Ahmed, the photographer.

Woman recovered from Pakistani Army bunker at Mymensingh. 12th December 1971. ? Naibuddin Ahmed/Drik/Majority World

Woman recovered from Pakistani Army bunker at Mymensingh. 12th December 1971. ? Naibuddin Ahmed/Drik/Majority World

I spoke to Naibuddin Ahmed on Sunday night (March 23), over the telephone. ?Why don?t you come and get a print? It?s only an hour, or a one and a half hour?s drive.?

The next morning Shahidul and I went off to Paril Noadha in Shingair, Manikganj, to Naibuddin bhai?s idyllic home, where he leads a retired life. Thirty-eight years later.

The Pakistani army, he said, had camped at the Bangladesh Agricultural University in Mymensingh. They had captured and occupied Mymensingh on April 19. When the army left in December, when they were forced to flee, people rushed to the BAU campus. Looting began, army bunkers, storeroom, there was looting all around, everywhere. Common people were looting, they were all over the place. ?I do not know whether it was from rage, or what…,? he gently added.

That?s when we heard the news, he said. Girls had been discovered in the bunkers, which were next to the university guesthouse. He went on, I went and found her, she was lying like that. People were milling around her, they were in front of her, they were behind her. I asked them to move, I made some space, and then I took photographs. It was the twelfth of December, that was the day Mymensingh became free. The Indian army had entered the town, they had entered the campus, they had taken control.

When I approached her, she seemed to be in a trance. There were others. I heard eight to ten girls had been found in the bunkers, some had already left. I found her alone. She did not respond when we called out. Her hands were raised. She was holding on to the pole behind her. Was that all that was left, nothing else to hold on to?

We returned to Dhaka with the print. Naibuddin bhai?s words kept ringing in my ears. Of course, it was a tamasha, a spectacle, he had said. There were people, both men and women who had come in search of their daughters, and their sisters. But there were onlookers, too. They had stood and stared. They did not share their pain and suffering, their helplessness. They looked on and thought, the military has done it to them. Nothing left. They are finished.

War rape intimidates the enemy, says Sally J Scholz. It demoralises the enemy. It makes women pregnant, and thereby furthers the cause of genocide. It tampers with the identity of the next generation. It breaks up families. It disperses entire populations. It drives a wedge between family members. It extends the oppressor?s dominance into future generations.

The context of war makes it different from peacetime rape. Although there are, often enough, compelling links between the two. The context of war alters perceptions. War turns rape into an act of a state, nation, ethnic group, or people. Atrocities committed by soldiers against unarmed civilians during wartime are always considered to be state acts, the Pakistani state against the Bengali peoples. Rape is an act of violence. It is an act of power and domination, rather than an act of sex. Rape is a demonstration of prowess, of male bonding, especially within the military. War rape, at times, becomes an end in itself. It creates a war within a war, by targeting all women simply because they are women.

Normal lives, distanced lives

?In Britain, you would never find such violent images in museums, or exhibitions. Generally speaking, no. Never, ever.? David, my niece Sofia?s Scottish husband, and a journalist, uttered these words slowly and thoughtfully, as we left the Muktijuddho Jadughor. Of course wars were violent affairs, he nodded in agreement, as I went on to ask which particular images had reminded him of Britain?s rules of museum display. Was it the photo of vultures eating human carcass? Was it photographs of dead bodies half afloat in the water? Rayer Bazar intellectual killings? Dead bodies of men, women and children struck down by the December 1970 cyclone? Rape victims of 1971?

I thought of the care with which images are graded in Britain, the consideration that goes into classifying cinemas into those not suited for viewing by children (above 12 years only, 15+ years).

But violence is cloaked in many ways. War machines kill. I thought of the care with which Blair had been sales agent to 72 Eurofighters to Saudi Arabia. Of the appreciation showered on India for its ?1-billion order with British Aeropace for Hawk trainer jets. An island of normalcy that outsources violence?

What if violence sown elsewhere manages to come home, to find its way onto TV channels? The chief military spokesman for coalition forces in Iraq Brigadier General Mark Kimmitt had been asked what if one comes across images of Iraqi civilians killed by Americans on TV? ?Change the channel,? had been his advice.

Those whose lives are devastated by war struggle to reconstruct a normal life after war. But recreating normal relationships is not easy. Much less so, for women. Marium, the central character in Shaheen Akhtar?s Talaash (novel), had been a rape camp inmate during 1971. After liberation, and many episodes, Momtaz marries her. He is a nouveau riche businessman, and amazingly enough, not at all concerned about Marium?s wartime experience. Momtaz does not worry about fathering children. Let us enjoy life first, he says. But the act of enjoyment is fraught with difficulties. If Momtaz holds her passionately, Marium?s eyes float like a dead fish. She is ready. Too ready. She starts breathing from her mouth. Her heart beats rapidly, like a mouse caught in a rat-trap. In the beginning, Momtaz was not worried. The women in the park would do the same, one hand outstretched to take cash, while the other would part clothes while she lay down. Petting, caressing were not required. The quicker the better, especially before the police appeared. But this is home, not a park. This is a conjugal bed, not one made of grass. Why does Marium behave like a whore? Why does she never say ?no?? Why does she not take part? Why is she inert? Why does she act surrendered, as if someone was holding a gun to her head, was forcing her to have sex? Momtaz begins drinking heavily. He wants to make his wife sexually active, he gradually turns into a rapist. He is physically abusive. He starts to behave like a member of the Pakistani army. The marriage does not survive.

War fractures the lives of survivors, often in ways that cannot be repaired. War rape creates a war within a war. It can outlive war. Pre-war normalcy often eludes the survivors forever.

Closer to truth. Closer to freedom

Thirty-eight years on and I look at myself. I look at us women. I look at our normal, peacetime lives. And I wonder, if justice had been done, if the war criminals had been tried, if women had returned to their families, to their parents, husbands, lovers, brothers, if they did not have to go to Pakistan, or to brothels, or to Mother Teresa?s in Kolkata, if those pregnant could have their babies if they had wished, would my life, would our lives have been differently normal? If justice had been done, would the rape of hill women have been a necessary part of the military occupation of the Chittagong Hill Tracts? Would the offenders have enjoyed impunity? Would there not have been independent judicial investigations? Would those guilty have gone unpunished? Would the Chittagong Hill Tracts have been militarily occupied at all?

Would we have been closer to freedom?

First published in New Age 26th March 2008

Jyotirmay Guhathakurta and Basanti Guhathakurta with seven year old daughter, Meghna and nephew Kanti in Gandaria, Dhaka, 1966. Bangladesh.

Jyotirmay Guhathakurta and Basanti Guhathakurta with seven year old daughter, Meghna and nephew Kanti in Gandaria, Dhaka, 1966. Bangladesh.  Choles Ritchil. Photographer unknown

Choles Ritchil. Photographer unknown Mutilated body of Choles Ritchil. Photographer unknown

Mutilated body of Choles Ritchil. Photographer unknown Cleaners clearing debris outside the Rangs Building to make way for traffic. Early hours of the morning. 8th December 2007. Dhaka. Bangladesh. ? Zaid Islam

Cleaners clearing debris outside the Rangs Building to make way for traffic. Early hours of the morning. 8th December 2007. Dhaka. Bangladesh. ? Zaid Islam Demolition workers who have set up their own emergency team, warm themselves at night. 8th December 2007. Dhaka. Bangladesh.

Demolition workers who have set up their own emergency team, warm themselves at night. 8th December 2007. Dhaka. Bangladesh.