Subscribe to ShahidulNews

By Satish Sharma

Forget about the power that, according to Mao, flows from the Barrels of Guns!

A lot more power actually flows through the matte black barrels of lenses. Camera lenses! And this is a power that flows a lot more silently and, most of the time, it works it magic very subtly.

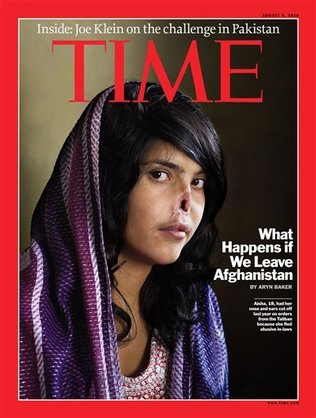

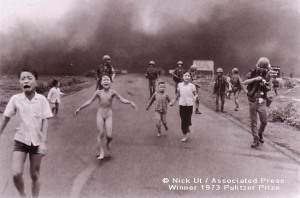

Very rarely do pictures explode on the media scene like the now infamous cover picture on the August 9th issue of Time magazine. Very rarely do pictures present us with such a questionable and ?teachable? moment about photography and its political uses. Rarely do photographs become such a powerful peg for discussions that go on and on. Discussions that need to go on because we have to understand, dissect and discuss the spaces that photography occupies in contemporary society. Spaces that are hardly any different from the times when photography was a medium controlled by the political and secret department of a British colonial government. Photography, we have to remember, was invented at a time when colonialism was at its height and became a major player in the colonial game. Something that British army cadets, who were to be posted in the colonies, were specially taught and equipped for.

Images of Afghanistan by Mohammad Qayoumi (prior to CIA intervention and Russian invasion).

Photography is a powerful language, a valuable voice of authority for authorities. One has to understand how it is used. A ?Writing with Light?- Photo Graphy is becoming more powerful than any other human language. It is more than just the world?s first universally understood language, one that needs no translators and appears to have no word language limitations because it is a technology driven by newer and newer technologies which give it a reach and power that no language ever had.

The endless flow of camera constructed pictures is, today, increasingly constructing our social and political landscape. Constructing us, actually, by manipulating the mental spaces that we live in. Defining our Drishti – our perception and very sense of self ! There are, after all, more photographs shot every year than there are bricks in the world. And photography, in its different, camera lens based, avatars (film and television, for example) is what makes us what we are -who we are manufactured to be.

Cameras construct our worlds in ways that word oriented languages did not because the visual language they present us with is perceived to have credibility, a veracity and a connection to objective truth that words did not. Pictures are becoming the bricks that construct our contemporary, increasingly visual world. A world that can no longer just ban the making of pictures as it once did or tried to do. A world in which technologies drive the move away from the word driven and language riven cultures towards vast visual information landscapes that are increasingly becoming part of a real, war driven, information wars . Wars that are, says the Project for a New American Century, about Full Spectrum Domination.

Domination that is blatant about not allowing any challenges ??military, economic or cultural?. Domination that seeks ?control of all international commons including Space and Cyberspace, Culture not excluded? and is driven by never ending wars that see whole societies as a battlefield. A battlefield where – in the language of the US Marines? ?Fourth generation Warfare? ? ? the action will occur concurrently- throughout all participants depth , including their society as a cultural and not just as physical entity?. Special Human Terrain teams now work alongside the American Armed Forces. These anthropologists, ethnographers etc are uniformed cultural warriors. They are, very problematically, working in battlefields to understand and subvert cultures and peoples. Humanity is now a terrain to be controlled.

It is against this background of militrarised information and cultural control that one needs to look at the Time magazine cover. It was its founder, after all, who first projected the idea of the 20th century as ?An American Centrury?. Henry Luce founded a media empire to project his agenda. Time, Fortune, Life and even the March of Time film series served to mediate his synarchist ideas of corporate control of political power. That he was a member of Yale university?s secretive Skull and Bones society like so many other American leaders, only adds to ones suspicions of hidden agendas.

Continue reading “Power from the barrel of a lens”