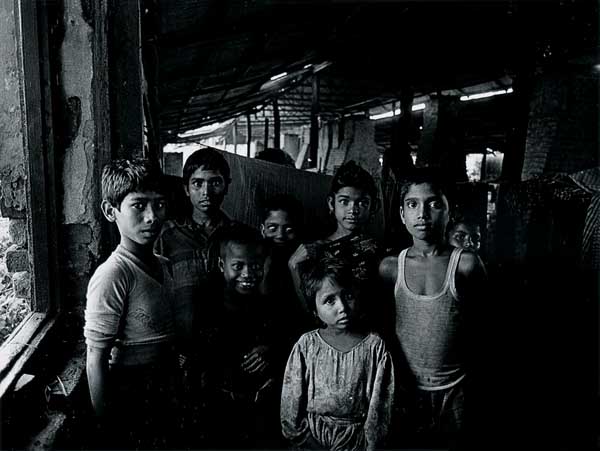

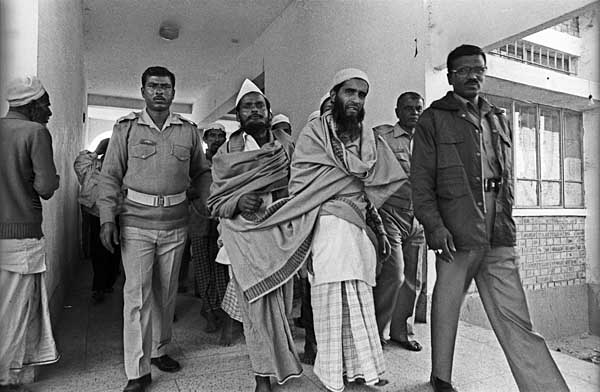

Journalist Jahangir Alam Akash talking of being tortured by military while pursuing an investigation. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World.

Journalist Jahangir Alam Akash talking of being tortured by military while pursuing an investigation. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World. In an email Jahangir informs us: yesterday night, police went my previous house of uposhahor in rajshahi for arrest me, when i attend in a roundtable in dhaka in presence of amnesty international secretary general irene khan.

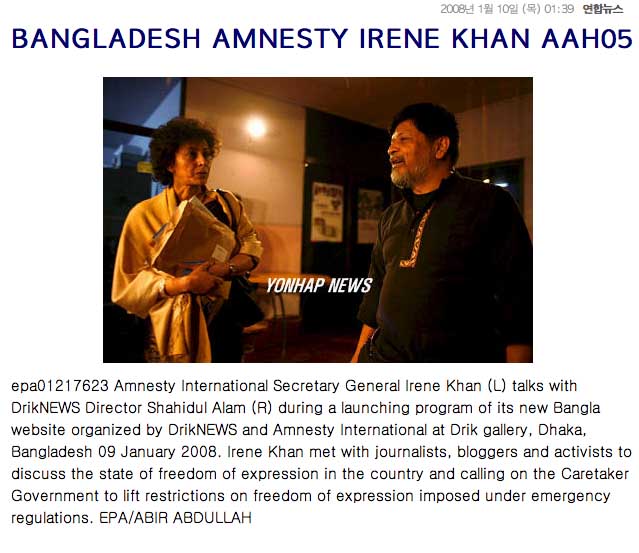

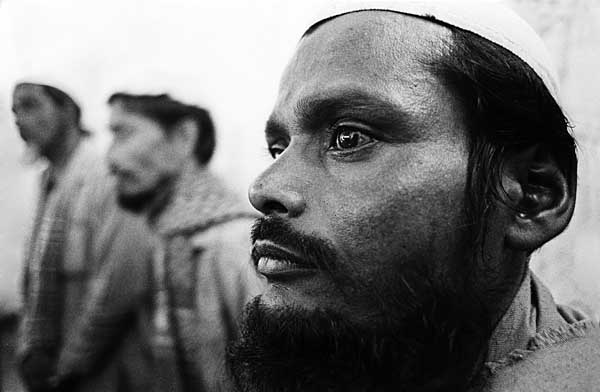

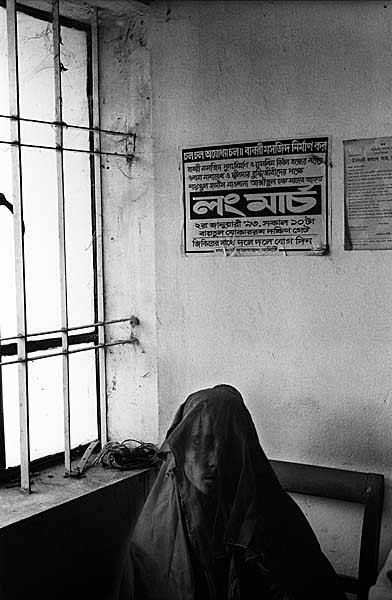

Participants at “Freedom of Expression” roundtable at Drik on 9th January 2007. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

Participants at “Freedom of Expression” roundtable at Drik on 9th January 2007. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

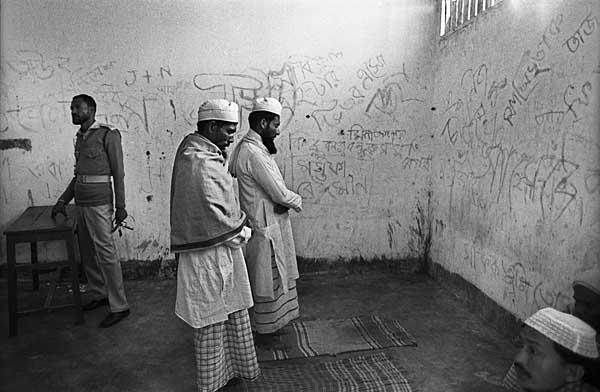

Irene Khan, secretary general of Amnesty International speaking to participants at the “Freedom of Expression” roundtable at Drik. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

Irene Khan, secretary general of Amnesty International speaking to participants at the “Freedom of Expression” roundtable at Drik. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

Transcription by Asif Saleh/

Drishtipat

Thanks to the technical team who helped set this up.

=========

greetings

the secretary general of amnesty international irene khan is with us

Shahidul Alam introducing

Irene Khan is not only a Bangladeshi but also first muslim woman head of Amnesty

We will have this show in a different format than usual

This will be a discussion and not room for speech

We want to create dialogue

Shahidul thanking all.

Irene introducing speech with a history of Amnesty

Irene talking…when I am in bangladesh from higher level it seems there is a lively media

But there must be another story

I met the army chief today and expressed my views about freedom of expression

For years now we have picked up a steady stream of journalists who have been attacked and wounded

In times of change we desperately need room for freedom of expression.

I am going to try get a complete picture from every one.

Shahidul now saying we are going to try to keep the discussion small

My name is Akash

I used to work for CSB new

The roundtable is very important for me

I want to get a little bit of time for myself.

because my rights have been severely hampered

Akash describing the story of how his rights were violated

I reported a story in CSB news when a father was shot by RAB infront of his daughter and I got persecuted for this.

Akash describing the process in details….how he has been fleeing for 3 months

he has been living a crippled life for the past 3 months

The oppression that happened to me

Akash has broken down in tears

Describing the judicial process.

Even though the high court has given him bail but still the local court still has issued a warrant against me.

There may be a lot more Akashes out there

Jahirul Huq Tito , Manik Saha to name a few over the years.

I want to live a free life

I want to go back to my profession.

and work for humanity

I want to dream of a new Bangladesh…I don’t want the oppression that has happened against me to happen to any body else,

Irene is speaking

We knew about your case

When you were in detention, I explained your case very forcefully to the foreign adviser.

You said that you do not want justice but just want to live and that shows the desperation of the case.

I want to assure you that Amnesty will do every thing they can.

parvin Sultana asks whether irene feels that we have press freedom in Bangladesh

sanjib drong of adivasi forum speaks..

Describes the case of Cholesh Richil..who was killed on March in Modhupur.

by the joint forces

The killing on the indigenous community is always justified.

I want to request you to take up the case of cholesh richil and follow through.

The perpetrators know that if indignous leaders are killed then nothing happens and that is only going to encourage more killing

I would like Amnesty to find out at what stage the investigation reports are held

Irene speaks.

Irene: We have already picked up the case and already spoke to high level cases.

High level admins

There has been no prosecution on the case

A crime has been committed but no justice has been serveed.

Pavel partha speaks

I want to highlight the violence of the multinational companies.

Companies like Monsanto ..

Our natural resouces are being stolen,

cases like Phulbari is an example of what multinationals can do in the name of progress

Corporations are violating our rights

we want to know what Amnesty can do to highlight this…

Faruq Wasif of Prothom Alo speaks

thank you irene..

Your coming to Bangladesh and solving individual cases are not the solution

we want to highlight the case of 1971….Amnesty was silent during the war of 71

Similarly your stand in this visit was very mild.

Doesn’t it show a very tolerant view of Amnesty towards military regimes?

Omi Rahman Pial speaks from bdnews24…

I am a blogger

What is the limit of my work?

I see Akash in front of me and I fear what may happen to me and what I need to do so that it doesn’t happen to me?

We have lots of irregularities and working under lots of pressure…

I can’t publish news at the right time because our internet will be brought down , calls will be made etc.

Jornalist from Samakal

We are living in an era of depression rather than free expression

I want to hear from Irene — how is she explaining Bangladesh’s current state.

I want to understand the total role of Amnesty in current Bangladeshi situation.

Anisur Rahman from New Age speaks

Cholesh is from my village

Cholesh was a symbol of free expression as well.

Cholesh used to speak for others in the community.

That’s why Cholesh was targetted

They tried not to kill the person Chalesh but silence a whole community.

Garments workers are not getting their salaries but when they are protesting, they are being taken to court.

Also want to highlight the case of tasneem khalil

We don’t know where he is today,

He was a blogger and a journalist at Daily Star.

We are seeing freedom of expression only for a few folks in certain commissions of the government.

He is now talking about some inconsistencies on tax loop holes

not sure..why 🙂

those who are on the web…this is not alam…but asif.

Shahidul asks to keep things shorts

Biplab Rahman , a blogger and journalist speaks

highlights internet monitoring.

telephone tapping

I have done a lot of research on Chittagong Hill tracks

and I want to highlight why mobile network is not there is those 3 disrticts

Therer were towers placed by the telecom companies but it was taken down by the local armed forces

I wanted to highlight the cases of university teachers as well…and think they should be released

Tipu Sultan from Prothom Alo speaks.

The journalists outside Dhaka lives under severe restriction

All the news are screened by authorities

They can not send the news of fertiliser crisis because of joint forces restrictions

They regularly face the threat of extortion cases from the local forces

But the authorities in Dhaka know this but they still deny it.

BUt the Dhaka journalists are doing much better compared to them.

Yesterday there was a case like that in Thaurgaon.

Udisa Islam speaks

Freelancer ..used to be in tv

Another introduction of mine is — I am the wife a teacher who were detained in Rajshahi University,

I am hearing a lot of sad stories..

but what is the worth of presenting this here?

We need to share this stories with each other ALL the time

This I am saying as a grassroots journalist,.

Last Aug 22nd whatever happened in bangladesh, everyone knows

Similarly whatever happenned with the museum statues.

The media played a brave role there.

How were those published and not some other stories?

Journalists oppression goes on for years!!

Its not because of state of emergency

Tipu Sultan (another victim) was not created under State of emergency (SOE)

it will happen again and again.

We need to talk about the whys of that..

Are we going to talk about the 20 students that still in prison from the university crisis?

Hana Shams Ahmed of Daily Star speaks

I want to highlight the kind of censorship after 1/11

We are very demoralised

speacially after the arifur Rahman incident.

We are very demoralised…and we can talk any thing about religion or army,

priscila raj speaks

Want to highlight three things….

Extra judicial killings

How can we work with International orgs to stop creatiion of organizations like RAB

In cases of State of emergency the most suffered are the people who are the most vulnerable in the society ..like the adibashies (indigenious community)

Lastly why do we never see the results of enquiry reports of the investivative commissions

Zaid Islam a photo journalist speaks

Sara Hossain speaks

I am here as a lawyer who represented some of these journalists who were victims in the last few years.

We need to talk about what we can do to stop this.

We always complain about internation conspiracy but we need to work in our own houses as well.

We don;t coordinate our work,.

I highlight time to the stories about slum dwellers and I send the reports to you journalists but no journalists show any interest..

But that is not the case if the story is about a big politician’s bail.

Amirul Rajib, a photo journalist speaks,

When a big crisis happens and media highlights the issue a lot but not many people are found to help them.

other than the family

We don’t have a infrastructure…

to handle these cases.

we all have to have our own personal network…

How can Amnesty help in all these cases to build an infrastructure.

to handle cases of oppression,

and also cases of regular engagement with the grassroots is needed from int orgs.

Anis highlights that no local journalist in Modhupur highlighted Cholesh’s case because they knew that that they will not survive if they highlighted that.

Ataur Rahman of journalists forum thanks to portray the current picture of bangladesh media today.

Amnesty needs to have a presence in Bangladesh.

I want to blame Amnesty for today’s crisis somewhat.

they need to have a presence in Bangladesh.

We have to look at what is happening in South Asia as a whole as well.

Amnesty needs to play a much stronger role.

here

Another question speaking about how unfairly he was sacked from Amnesty Bangladesh 5 years ago.

Najma Chowdhury from Shwadesh Khabor Weekly…

Do you think anything will change after your visit, Irene Khan?

Chandan Shaha from a weekly,,,

He highlights a case where a minister was sacked because of taking a bribe from a multinational

and wonders why the minister got sacked and nothing happened to the multinational.

Irrelevant talk about corruption of govt

Does Amnesty have a way to research these stories? Shouldn’t they already know these things?

Someone from Manusher jonno speaks

tallks about child rights in Bangladesh

what to do for children prisoner?

Shafiqul Huq Mithu speaks about jahirul Huq Tito in Pirojpur.

another journalist who has been taken in to jail by the admin.

Highlighting details of Tito’s ordeal with the court and but law enforcement agency.

Shahidul speaks,

Highlighting the permission that he had to take for the event..

at World press freedom day.

which says that there you can not criticise the govt in such cases.

We are violating law here by criticizing the govt…Shahidul mockingly reminds Irene,

You all highlighted a lot of cases here..

As journalist you tend to be in the present.

But the activists have to take a longer term perspective..otherwise it gets very depressing…

You all talked about today…but we need to talk about the past as well.

When you take a long term view of human rights, there is not a supported political system where human rights are violated…

go back from 1971…there is a thread of impunity where human rights violations have been left unquestioned

National Human Rights Commission is something that can be very powerful

Whether it is going to be a watchdog or a lapdog, it will all depend on how much pressure we ALL can create

A lot of people told me that this year extra judicial killiing have been reduced…but I am not satisfied by such replies.

We need to highlight why they are going on and what is being done to stop it.

ON freedom of expression..

Irene asking why all the draconian rules are necessary under state of emergency..

These rules are hanging like an axe?

for people..

One think that that has struck me after talking to a lot of people…

civil society and govt have understood clearly how they can use international laws and international civil society to protect the human rights in Bangladesh.

One thing to highlight is there is a worldwide network of human rights defenders.

Today’s event is being captured by people worldwide and that says a lot.

about this network,

We have an enormous opportunity in the internet to create a worldwide network..

that is why Amnesty is starting a Bangla Human Rights Portal for everyone.

I hope you all will take part in it and create a network.

What I am saying is not going to solve the problems.

But if we all create a noise together and work for change, change will happen.

We All need to work together.

on this.

We are hoping we will be able to make our website more interactive.

http://www.amnesty.org/bangla

Irene talking about the question on economic and social rights.

and explaining the campaign on human dignity which focuses on poverty.

what is relationship with human rights and climate change , poverty etc …

This is just a partial transcript of the whole conversation that took place.

Faruk Wasif and Irene are having an exchange over whether West has monopoly on human rights

We are closing …

thank you all

Shahidul thanking,,,Naeem, Givan, Asif for organizing this and highlighting the collaboration of a lot of people.

Shahidul ends with saying that the movement is ours whether or not Irene Khan is there or not,

![]()

Pakistani soldiers surrendering on the 16th December 1971. ? Aftab Ahmed/Drik/Majority World

Pakistani soldiers surrendering on the 16th December 1971. ? Aftab Ahmed/Drik/Majority World Dismembered head at the Rayerbajar Killing Fields where intellectuals were slaughtered on the 14th December 1971 ? Rashid Talukder/Drik/Majority World

Dismembered head at the Rayerbajar Killing Fields where intellectuals were slaughtered on the 14th December 1971 ? Rashid Talukder/Drik/Majority World Victorious Mukti Bahini returning home at the end of the war. ? Jalaluddin Haider/Drik/Majority World

Victorious Mukti Bahini returning home at the end of the war. ? Jalaluddin Haider/Drik/Majority World Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on his return to Bangladesh from Pakistan. 10th January 1972 ? Rashid Talukder/Drik/Majority World

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on his return to Bangladesh from Pakistan. 10th January 1972 ? Rashid Talukder/Drik/Majority World Children amidst shells. ? Abdul Hamid Raihan/Drik/Majority World

Children amidst shells. ? Abdul Hamid Raihan/Drik/Majority World

Feature on Korean media

Feature on Korean media

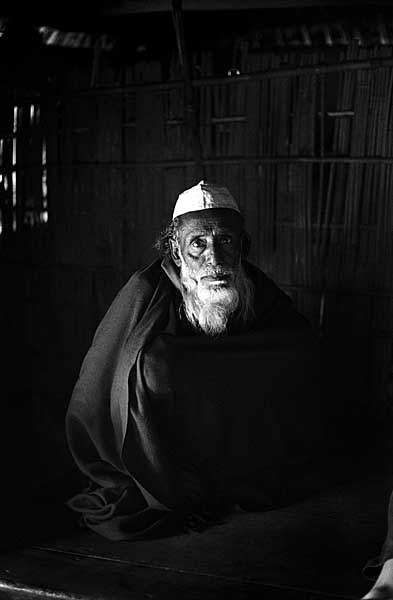

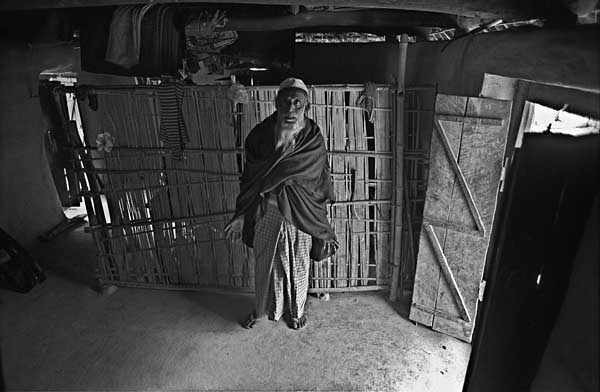

?I have lost a son, maybe I?ll lose another, but I won?t let them setup a coalmine here.? To Tahmina Begum who had lost her son Toriqul to police bullets, her land was also her family.

?I have lost a son, maybe I?ll lose another, but I won?t let them setup a coalmine here.? To Tahmina Begum who had lost her son Toriqul to police bullets, her land was also her family.  It could have been a ?B? rated western except that it is set in the east.

It could have been a ?B? rated western except that it is set in the east.  People wanting to hang on to their ancestral land versus mining companies wanting huge profits. There have been only minor changes from previous scripts. When farmers wanted fertilizers and seeds, the police had opened fire killing them, when they wanted electricity to irrigate their soil, the police had opened

People wanting to hang on to their ancestral land versus mining companies wanting huge profits. There have been only minor changes from previous scripts. When farmers wanted fertilizers and seeds, the police had opened fire killing them, when they wanted electricity to irrigate their soil, the police had opened  fire killing them. Now that they want to retain their land rather than have it converted into coal mines again the police have opened fire killing them.

fire killing them. Now that they want to retain their land rather than have it converted into coal mines again the police have opened fire killing them.  The Shaotals, being indigenous minority groups, find themselves even more vulnerable within this persecuted community. In the shootings on the 26th September 2006, in Phulbari, Dinajpur, in northwestern Bangladesh, at least six villagers are known to have been killed, over a hundred are said to be missing.

The Shaotals, being indigenous minority groups, find themselves even more vulnerable within this persecuted community. In the shootings on the 26th September 2006, in Phulbari, Dinajpur, in northwestern Bangladesh, at least six villagers are known to have been killed, over a hundred are said to be missing.