Shams al-Din Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Muhammad ibn Ibrahim ibn Yusuf al-Lawati al-Tanji Ibn Battuta was more commonly known as Ibne Battuta. Born into a family of Islamic judges in the Moroccan town of Tangier, he developed a thirst for travel after going to Makkah on pilgrimage in 1325 at the age of 21. He travelled extensively, going to Anatolia, East Africa, Central Asia, China, up the Volga, down the Niger, even in the tiny Indian Ocean sultanate of the Maldives. He kept meticulous records of what he saw, what he heard and the people he met. 29 years later, he went back home and wrote about his experiences with the help of Ibn Juzay, a young scholar. He was little known when he died in 1368 as his rihlah was not respected as a scholarly piece of work. Continue reading “Battuta Was Here”

Category: culture

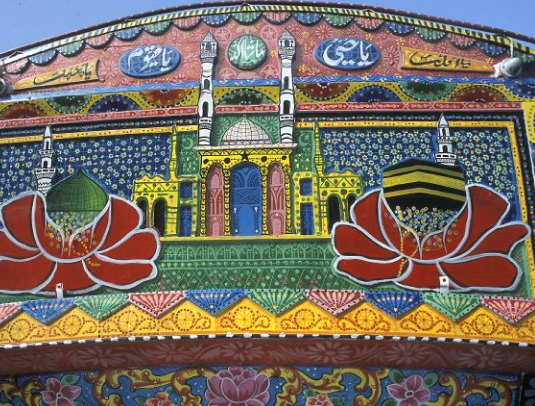

Masterpieces To Go

Another non-terrorist Pakistani story.

Under the shade of a colossal banyan tree, Karachi truck painter Haider Ali, 22, is putting the finishing touches on his latest creation: a side-panel mural of Hercules subduing a lion, rendered in iridescent, undiluted hues of purple, yellow, red and green. His 10-year-old nephew, Fareed Khalid, applies a preparatory undercoat of white paint to the taj, the wooden prow that juts above the truck?s cab like a crown. Like Ali?s father, who first put a brush into his son?s hand at age eight, Haider is carrying on a master-apprentice tradition with Fareed, who spends his afternoons in the painter?s workshop after mornings in school.

Power of Culture: Bangladeshi Spirit

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Over the years, February has become our month of resistance. This is the window that successive repressive governments have allowed us, to vent our steam. The open air plays in Shahid Minar, the book fare in Bangla Academy and of course the midnight walk and the songs of freedom on the night of Ekushey, the 21st February, are all tolerated, for one month.

Yuppie Bangladeshis put on their silk punjabis and saffron sarees, and become the torch bearers of our heritage, for one month. Come March, it will be business as usual. It has been difficult convincing development experts of the value of culture in our society. With ‘poverty alleviation’ being the current? buzzwords, one forgets, that it was the love for our language that shaped our resistance in ’71 or that ‘Bangla Nationalism’ has been used to justify repression in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. On the 1st February, perhaps we could look back at a collaboration between Drik in Bangladesh, and Zeezeilen in the Netherlands:

Power of Culture: Bangladeshi Spirit

Culture glides through peoples’ consciousness, breaking along its banks, accumulating and depositing silt, meandering through paths of least resistance, changing route, drying up, spilling its banks, forever flowing like a great river. Islands form and are washed away. Isolated pockets get left behind. It nurtures, nourishes and destroys. Ideas move with the wind and the currents and the countercurrents. Trends change, flowing in the slipstreams of dominant culture. A few swim against this current, while others get trapped in ox-bow lakes, isolated from the mainstream.

Photography, more than any other media or art form has influenced culture. Photographs in particular take on the dual responsibility of being bearers of evidence and conveyers of passion. The irrelevant discussion of whether photography is art has sidelined the debate from the more crucial one of its power to validate history and to create a powerful emotional response, thereby influencing public opinion. The more recent discussions, and fears, have centred on the computer’s ability to manipulate images, subsuming the more important realisation that photographs largely are manufactured by the image industry, one that is increasingly owned by a corporate world. The implied veracity of the still image and its perceived ability to represent the truth hides the ubiquitous and less perceptible manipulation enabled by photographic and editorial viewpoint. Not only can we no longer believe that the photograph cannot lie, we now need to contend with the situation that liars may own television channels and newspapers and be the leaders of nations. Given the enormous visual reach that the new technology provides, the ability to lie, is far greater than has ever been before.

Photography has become the most powerful tool in the manufacturing of consent, and it remains to be seen whether photographers can rise above the role of being cogs in this propaganda machine and become the voice for the voiceless.

Dhaka Traffic Blues

Politically Correct Eid Greetings

Well, the long holidays are over, and the streets of Dhaka are slowly getting back to their normal frenzy. The horns, the put-put of the baby taxis, the bewildered stare of the taxi driver as he tries to interpret the gyrations of the traffic warden, the gentle smile on the bus driver as he parks the bus in the center lane waiting for the passengers to offload the chicken coops on the rooftop, the suicidal pedestrian who tries to cross the road over to Jahangir Tower in Kawran Bajar, the glee on Asma, the flower girl’s face as she spots me, and skips between two trucks, to my bicycle, knowing she has a sure sale, the babu in the back seat with the newspaper covering his face, the blind beggar coughing through the thick black smoke of the BRTC double-decker are some of the familiar signs that tell me that there is stability in my life and the world has not changed. In this season of greetings, and eco conscious, politically correct messages, I send you a recycled, lead-free wish.

May you find a way to travel

From anywhere to anywhere

In the rush hour

In less than an hour

And when you get there

May you find a parking space

The year has had its usual ups and downs for Drik, but the adrenaline flowing due to the constant crisis management during Chobi Mela has everyone hyped up. The big show on the 10th January looms. The hits in the web site have climbed regularly, and the December total of 105,857 hits is an all time record for us. It’s a credit to you all for having stuck with us for so long.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

May the good light be with you.

Shahidul Alam

Wed Jan 3, 2001

Ruhul Amin's Story

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

The streets of Dhaka looked far from festive last night. The eerie glow of the sodium lamps lit the mounted police and their dogs. There were said to be 5000 in the streets. The barbed wire barricades and the stop searches, put a damper on the marauding young men prowling the streets, but the packed dance floor at the Gulshan Club seemed unaffected by it all. The TSC corner at Dhaka University, on the other hand, was an all male affair. The police presence was not reassuring enough for women to enter the macho fray.

As I opened the greeting cards that wished me well for the new season, I kept remembering how different was Eid for the Afghans from Christmas for the US Marines.

I remembered my delight as a child, when we would look out of the rooftops for the new moon. We would bathe early in the morning and go out with our friends, all decked in our new clothes. Alert to the idea that a few smart salaams could net some extra pocket money.

For Ruhul Amin, in this story by the children of Out of Focus “Season’s Greetings” perhaps has more to do with going back home to the village, than with Christianity or Islam, or the celebration of Bangla or Chinese identity.

“I was born in Mirpur, Dhaka, and I have grown up here. When I was 8 or 9 years old, I went to my village home for the very first time. I loved it there. I met my grandparents from my mother’s and my father’s side, and they were very happy to see me. So I asked my mother, why did you leave everybody here and move to the city?

In the coming days, I wish for you and I, and Ruhul Amin and the children of Out of Focus, less murderous and warmongering leaders.

Shahidul Alam

Tue Jan 1, 2002

When The Mind Says Yes

It was in the foothills of the Himalayas that he was born. In a bullock cart amidst a snowstorm. It was in the cold chill of January, in the severest winter in Bangladesh’s memory, that he died. Alone and uncared for, the frail old man shrunken with age, but with a heart as wide as the ocean, and a mind as young as the children that he loved, Golam Kasem, nicknamed Daddy, died at the tender age of 104. The single storied yellow building at 73 Indira Road, with its unkempt garden, was home not only to Bangladesh’s oldest photographer, but also the first Bengali Muslim short story writer.

Born on the 5th November 1894, Daddy lost his mother shortly after birth. Brought up by his aunt, the young man took up photography the way many young men take up many things, to impress a young girl. She had promised to cook for him if he could develop a film that others had failed with. Kasem embarked with the same trait for disciplined research, that he maintained till his death. He went round the studios of Mednapur to find out the method that would win him his meal. He never talked of what the meal was like, but did describe how he used a hardner to prevent the emulsion from peeling off. Saving his bus fare to school to buy a brownie camera, he began taking photographs of the things he loved most, animals, flowers and children. And importantly, he preserved those negatives. In his archives, amidst old paper sachets marked in his neat handwriting are glass plates dating back to 1918. The harbour in Calcutta, early steam engines, the Gurkha regiment in shorts, and many many portraits. Period pieces lit in that soft natural light that early studios used.

Grainless negatives of people, generally in studied poses. His spontaneous pictures were those of animals and children, and amongst them are some gems. “Her first dance” is a delicate photograph of a child amidst a twirl, centre stage with her family as an audience. Strong portraits of his friend a teacher and the calm portrait of his grandmother belie the fact that he was an amateur, who took photographs for fun. He sold his first photograph at the age of 98, for Drik’s 1991 calendar.

The founder of the Camera Recreation Club, Daddy arranged regular meetings at his house in Indira Road where the club was housed. Regular visitors included poet Sufia Kamal, painter Qamrul Hassan and photographer Manzoor Alam Beg. His letters were hand-written, each one numbered, and the envelopes often made of recycled newspapers or book wrappings. Competitions at the Camera Recreation Club were unusual events. Photographers who would abstain from many local competitions would submit those small 4″ x 5″ prints. And they were proud of the simple prizes they sometimes won. The prize giving was always accompanied by a cultural programme. And Daddy would always sing.

The room next to his bedroom was his darkroom. A red plastic bowl stuck under a light bulb, his safe light. He mixed his own chemicals from old tins of chemicals. Often I would get a SOS. The same neat handwriting, asking for potassium ferricyanide or some other chemical that he needed for his latest experiment. Photography was his passion. Once at a meeting at the Bangladesh Photographic Society (BPS), where he had been presented a new camera, Daddy spoke of how the camera he had been given would be much more than a machine to him. He talked of how he kept his camera next to his pillow when he went to sleep. How, when he was sad, he would speak to it, and that it would talk back and comfort him. Unimpressed by the modern motor driven models, his preference was for a simple manual SLR, “preferably not too heavy” he would add with a mischievous smile. That is not to say he was shy of technology. I remember him holding up his thick glasses to read his first Email from his grandson in Canada. He asked me to come back the next day, and as I parked my bicycle by his rose garden, he was ready with his answer, again written in his neat handwriting. He was fascinated by Email and used it regularly, and curious about how the message would get through the ether.

He was fiercely independent. He cooked his own meals, fed his dog and his cats and did his own shopping. Until recently, he would even go on his own to a house down the road and guide himself up the stairs to meet a lady friend whom he occasionally visited. Rarely would he talk of himself and it was only in passing conversation with the late Mr Nasiruddin that I discovered that Daddy was the first Bengali Muslim short story writer. He used to write regularly for Shawgat, and continued to write, both technical articles on photography for the BPS newsletter, and short stories for general publication. His last manuscript, a simple manual on photography, sadly lies in my hands, unpublished. He had dearly wanted it printed before he died. The proofing was complete, the photographs selected, but ‘matters of consequence’ allowed other projects to take precedence. His last note, urging me on with the publication, will forever haunt me.

Always articulate, on his 100th birthday, at the opening of a joint photographic exhibition by him and the other photographic guru Manzoor Alam Beg at the Drik Gallery, he talked eloquently of how photography was the way for people of the world to make friends, to break barriers, to discover one another. Later as the chief guest at the opening of the 1996 World Press Photo, he talked of his own struggle to overcome the limitations of an ageing body. “My body says no, but my mind says you must, and in the end it is the mind that wins.” On Friday the 9th January 1998, the body finally said no and the mind took wings.

Please Retweet #photography #Bangladesh #archives #Drik

Changing their destiny

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

www.newint.org/issue287/contents.html

Letter from Bangladesh

Changing their destiny

Shahidul Alam travels with the poor who chase a dream to distant lands.

They all have numbers. Jeans tucked into their high-ankled sneakers. They strut through the airport lounge, moving en masse. We work our way up the corridors leading to the airplane, but many stop just before boarding. The cocky gait has gone. The sad faces look out longingly at the small figures silhouetted on the rooftops. They wave and they wave and they wave. The stewardess has seen it all before and rounds them up, herding them into the aircraft. One by one they disengage themselves, probably realizing for the first time just what they are leaving behind.

As in the case of the others, his had been no ordinary farewell. They had all come from the village to see him off. Last night, as they slept outside the exclusive passenger lounge, they had prayed together. Abdul Malek has few illusions. He realizes that on $110 a month, for 18 months, there is no way he can save enough to replace the money that his family has invested.

But he sees it differently. No-one from his village has ever been abroad. His sisters would get married. His mother would have her roof repaired, and he would be able to find work for others from the village. This trip is not for him alone. His whole family, even his whole village, are going to change their destiny.

That single hope, to change one’s destiny, is what ties all migrants together ? whether they be the Bangladeshis who work in the forests of Malaysia, those like Abdul Malek, who work as unskilled labour in the Middle East, or those that go to the promised lands of the US. Not all of them are poor. Many are skilled and well educated. Still, the possibility of changing one’s destiny is the single driving force that pushes people into precarious journeys all across the globe. They see it not merely as a means for economic freedom, but also as a means for social mobility.

In the 25 years since independence the middle class in Bangladesh has prospered, and many of its members have climbed the social ladder. But except for a very few rags-to-riches stories, the poor have been well and truly entrenched in poverty. They see little hope of ever being able to claw their way out of it, except perhaps through the promise of distant lands.

So it is that hundreds of workers mill around the Kuwait Embassy in Gulshan, the posh part of Dhaka where the wealthy Bangladeshis and the foreigners live. Kuwait has begun recruiting again after the hiatus caused by the Gulf War, and for the many Bangladeshis who left during the War, and those who have been waiting in the wings, the arduous struggle is beginning. False passports, employment agents, attempts to bribe immigration officials, the long uncertain wait.

Some wait outside the office of ‘Prince Musa’ in Banani. He is king of the agents. His secretary shows me the giant portraits taken with ‘coloured gels’, in an early Hollywood style. She carefully searches for the admiration in my eyes she has known to expect in others. She brings out the press cuttings: the glowing tributes paid by Forbes, the US magazine for and about the wealthy, the stories of his associations with the jet set. She talks of the culture of the man, his sense of style, his private jet, his place in the world of fashion.

Apart from the sensational eight-million-dollar donation to the British Labour Party in 1994 ? which Labour denies, but which the ‘Prince’ insists was accepted ? there are other stories. Some of these I can verify, like the rosewater used for his bath, and the diamond pendants on his shoes (reportedly worth three million dollars). Others, like his friendship with the Sultan of Brunei, the Saudi Royals and leading Western politicians, are attested to by photographs in family albums.

He was once a young man from a small town in Faridpur, not too distant from Abdul Malek’s home or economic position, who made good. Whether the wealth of the ‘Prince’ derives mainly from commissions paid by thousands of Maleks all over Bangladesh or whether, as many assume, it is from lucrative arms deals, the incongruity of it all remains: the fabulously wealthy are earning from the poorest of the poor.

Whereas the ‘Prince’ has emigrated to the city and saves most of his money abroad, Malek and his friends save every penny and send it to the local bank in their village. Malek is different from the many Bengalis who emigrated to the West after World War Two, when immigration was easier and naturalization laws allowed people to settle. Malek, like his friends, has no illusions about ‘settling’ overseas. He knows only too well his status amongst those who know him only as cheap labour. Bangladesh is clearly, irrevocably, his home. He merely wants a better life for himself than the Bangladeshi princes have reserved for him.

An old friend of the NI, Shahidul Alam is guiding light of Drik, a remarkable photographic agency in Dhaka.

Chalking up Victories

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

At 17 Mozammat Razia Begum is older than most of the girls in her class at the Narandi School. She was married at 15 but her husband abandoned her.

?If I had been educated he would not have been able to abandon me so readily, leaving me nothing for maintenance,? she says. The marriage of young girls without proper contracts – followed soon after by abandonment – is a serious social problem in Bangladesh. Razia blames her parents. ?My parents were wrong to marry me off so young. If I had a daughter, I should not let her marry until she was at least 19.?

The school Razia attends is one of 6,000 non-formal village schools set up by BRAC – the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee – exclusively for pupils who have never started school and those who had to drop out. Three-quarters of the 180,000 pupils are girls. Although married girls are not normally catered for, exceptions are made. Many of the teachers are women: parents in Bangladesh frequently keep their daughters away from school if teachers are male. And each BRAC school is situated right in the community: if schools are far away parents will not let girls attend. It is not acceptable for girls – especially those past puberty – to walk about the countryside in this devout Muslim country.

?I am fortunate to be here,? says Razia, looking round the schoolroom with its tin roof and walls of bamboo and mud. She had to fight to come, though. Her father believes that a woman?s place is at home. ?Had I been a boy,? she said, ?my father would surely have allowed me to study.?

Razia?s own mother was married at 12 and, like her oldest daughter, had no say in the matter. ?I want my sisters? lives to be different. They should study and be given a choice about their marriage. Husbands will not dare to treat an educated woman badly.? On this subject, Razia becomes quite animated.

Razia would like to go on with her studies after she has completed the BRAC course. During the two-and-a-half hour daily session – which is timetabled to fit in with seasonal work and religious obligations – she learns literacy and numeracy, as well as enjoying activities such as singing, dancing, games and storybook reading.

BRAC have had a remarkable success in keeping the drop-out rate from their schools to five per cent and graduating 90 per cent of their students into the formal primary system. This proves that the obstacles to girls? education – even in such a poor environment – can be overcome.

As for Razia, her experience of life has forced her to question many things she once took for granted – such as the need to get married. She does not wish to marry again. And many other girls have begun to question the restrictions imposed on them. More of them want to be teachers – like their own teacher – or doctors. Razia says: ?I tell my sisters to study well and get a job. If they get a job they will be able to do as well as men and men will respect them.?

First published in the New Internationalist Magazine in Issue 240