Loona Bimberton had recently been carried eleven miles in an aeroplane by an Algerian aviator, and talked of nothing else; only a personally procured tiger-skin and a heavy harvest of press photographs could successfully counter that sort of thing. Mrs. Packletide had offered a thousand rupees for the opportunity of shooting a tiger without over-much risk or exertion. However, when the opportunity came, she accidentally shot the goat, and the tiger died of fright, and she had to settle with Miss Mebin so that her version of the story would be the one to circulate.

?The release of the hostages by the military, had all the hallmarks of Mrs. Packletide?s tiger hunt,? said Ching Kiu Rewaja Chairman Rangamati Sthanio Shorkar Porishod, the local government head. Unlike the story by the Indian born writer Saki, there were no press photographs to show here, but radio and television and the carefully fed press releases had been prepared so that the story of the heroic release of the two Danish and one British engineer in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, would circulated unchallenged. There had been a few hiccups, and the two separate government press releases on the same day, explaining the circumstances of the kidnapping, had cast shadows on the otherwise well orchestrated adventure story.

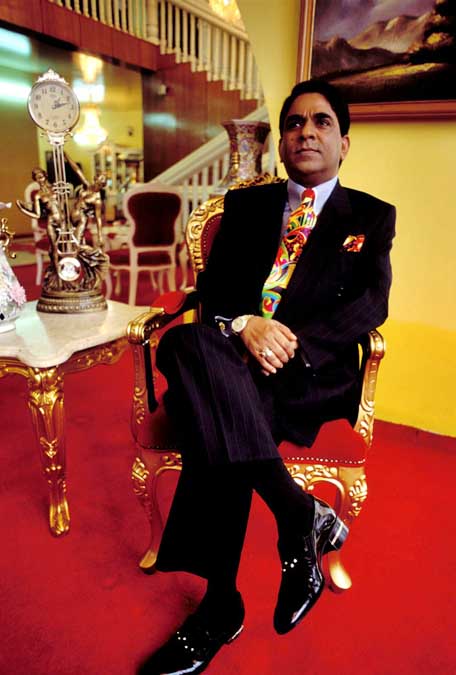

Ching Kiu Rewaja sat in his big government office, surrounded by a large number of people vying for his attention. He gestured grandly for us to sit in a position of honour as tea and biscuits immediately appeared. He was busy signing things and would stop momentarily to look up and apologise to us for keeping us waiting. ?There is a subtle competition here, civil administration, police, and military all wanting credit. And they didn?t want to share the credit, hence this deceit.? However, while the chairman understood the underlying politics, despite his colourful analysis, he didn?t really know. No one besides the kidnappers and the military knew exactly what had happened on that night, or the subsequent morning. Post release, the Danish engineers in distant

Copenhagen, had reconstructed the hours preceding the kidnapping. ?After a seven hour walk through the jungle we were led to a bamboo cottage, during the night. Then the abductors went into the jungle, and after some hours they heard some shootings, and soldiers shouting, ?you have been released by the Bangladeshi Army?.?

The Brigadier General Rabbani, who headed the military in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, did speak to us, and was extremely cordial, but would not give an official answer. Neither his version, nor the extremely vague government press releases, explained how both the military and the abductors arrived at the same remote spot at the same time, particularly when it takes so many hours to get to. How the abductors escaped, when they had the place surrounded, is mysterious, and the fact that no one from either side was the slightest bit hurt in this confrontation is a bit surprising. Given the secrecy surrounding the issue, the rumours have been flying, but certain significant facts do emerge.

- The incident (which took place less than 500 metres of the military camp) was not an isolated one. People were advised to keep some money, in case they were stopped by hijackers. This was common knowledge.

- In internal discussions, (which the police and military deny), there had been talk of compensation, even for incidents of rape that had been reported.

- Though the government claims that they have advised all donors to take police escorts, there appears to be no document in support of this claim.

- The early mediators had been suspected of being on the ?take? themselves, and later people were shuffled.

- There is resentment in the Chittagong Hill Tracts for some of the ?developments? being planned, particularly the establishment of a 218,000 acre ?reserve forest? which will take over further land from hill people, and the proposed construction of two extra units of the Kaptai Dam.

- There is a certain degree of ?tolerance? for the criminal activities that go on in the military protected zones.

While in general people in the government and others who are seen to be recipients of foreign aid clearly want aid to continue, there are hill people who question this development process. ?Who is the development for? If there is no peace then what will it solve? Once development funds were given, crores of taka were given. Bungalows and roads were given, but what did it do for the average person? The roads made it easier for the military, and for bureaucrats to live in, but these did not affect the general people. It might appear that a road will lead to progress, but it has been seen that roads have been used for taking away the forest resources, the trees and the wood, it has made the forests barren, now we even have floods in the hill tracts which we have never had. This increased inflow of people have pushed the people further back. The local people do not get the benefits of this development,? says Prasit Bikash Khisha: Convenor UPDF, who?s party has been accused by some of having orchestrated the kidnapping. An association that UPDF vehemently denies.

Others like engineer Kjeld J Birch, Senior Advisor, CHT Water Supply and Sanitation disagrees with the withdrawal of Danish development aid. ?The hospitality here is very good and kind, so it is difficult to understand that things have to be closed down. I don?t feel unsafe. On a personal level I wouldn?t feel worried. We never used an escort, except when the ambassador was here. Never have I had any untoward experience. Neither my wife. The people we have been in touch with, have been very protective. I think there is an overreaction.? But Birch, who left an attractive job offer in Bhutan to come to one which offered him ?a challenge? and his wife who left a job to accompany him are now both unemployed, so they too have personal interests to protect.

It is therefore difficult to sift the ?truth? from this rubble. But certain changes will have to be in place before development in whoever?s definition can be in place. Information has to flow to the people. A misinformed public will construe the worst, and the rumours currently circulating within the Chittagong Hill Tracts certainly do not favour the government. There has to be a greater degree of transparency in the way things are conducted in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The military will have to be more accountable to the people in both Bangladesh at large and the hill people in particular. People not affiliated to the government, or not necessarily in full agreement with the peace accord, need to be involved in matters affecting the future of the hill people, and that the zone must no longer be treated as a military zone. Within Bangladesh and within The Chittagong Hill Tracts, a democratic system has to give weight to marginalized communities. If these issues get addressed, maybe the kidnapping will have done more for Bangladesh?s development than the players involved had originally envisaged.

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them.

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them. When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’

When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’