Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

A photographer is rarely a good editor of one?s own photographs. It?s not as illogical as it sounds. The visual content within the four corners of a frame create the stimulus that inform us of what was seen, and in well crafted images, conjure up the sense of the moment. For the photographer, it is a small part of the process. The pain, the pleasure, the frustrations, the high, of arriving at the photograph, is an inseparable part of the image. The editorial choice therefore, cannot be made on the image alone. The emotional weight impinges upon one?s judgment. It is a valid choice, but one that the viewer unencumbered by that weight, is incapable of sharing, and hence a choice, less relevant to the viewer.

A teacher in selecting work by students goes through a similar process. The path is neither smooth nor predictable. Students with different ability, drive, tenacity and energy occupy a classroom. Work produced by a student one has nurtured over years is difficult to reduce to a set of visual frames. The coaxing, cajoling, willing and hand holding that has gone into each student. The stance one has taken, stern but generous, appreciative but demanding, kind but rigorous, finds its way into each image. Each portfolio has a stamp, invisible to others but clearly present to the teacher. How then does one take a dispassionate view, while selecting work for a collective publication?

Of course there is the chronology that maps out the growth of the organisation. The transitions that have taken place, contoured by collective experiences. The visiting faculties who have left lingering traces upon individual styles. Influences that have sometimes dramatically altered the visual practice. Return to familiar paths. Explorations into the unknown. Blatant copies arising out of adulation. Rejection, rethinking, a process of morphing where the old and the new have combined to produce a new genre altogether, are easy to observe. The branches can be traced to the roots with every knurled knot, every fork, every green shoot a sign of a new beginning.

Then comes the difficult part. When bright sparks of brilliance shine through in defiance. When a body of work refuses to be categorised. When another, just as strong, pulls in a different direction. How does one choose between favourites? How does one forget the angst that led to a new vision? When a student returns from being almost lost, and basks in new-found confidence, can work be excluded, merely because it doesn?t fit? Can brilliance be ignored merely because there are other stories to tell, and there just isn?t enough room?

Other dynamics also enter the equation. Talent and success don?t always go hand in hand. Having taught one?s students survival skills, one must appreciate their ability to get ahead, make the right impressions, learn to play the ?game?. In that game of life, there are those one admires more, for their integrity and honesty. For staying true to their beliefs. For not selling out. That the less scrupulous are sometimes the ones who shine is a reality one needs to accept. Having handed over the tools, one cannot hold back. It is arrogant to assume one?s value systems will be valued by all. In the rough and tumble of survival, many will choose options one might not fully subscribe to. Many will walk paths, one would hope they would avoid. Some will deceive, some will massage the truth. Some will benefit as a result. That too is reality.

When a reject pile is so rich with nuggets how does one lament? What message does it carry when rejection is so value loaded? When rejected work is seen as inferior. When the editors sword can affect careers, change lives. In the binary of inclusion, there is no middle path. No also-rans. Work is in, or out. The pain of losing out is not easily shared.

Hopefully, the book will speak for itself. While regretting what has been lost, one must not fail to rejoice in what is present. Inevitably there are internal references. New work that is informed by former attempts. While other bodies of work have marked the path for future students to follow. Global influences have also pitched in, but generally, it is the peers who have paved the way for future students.

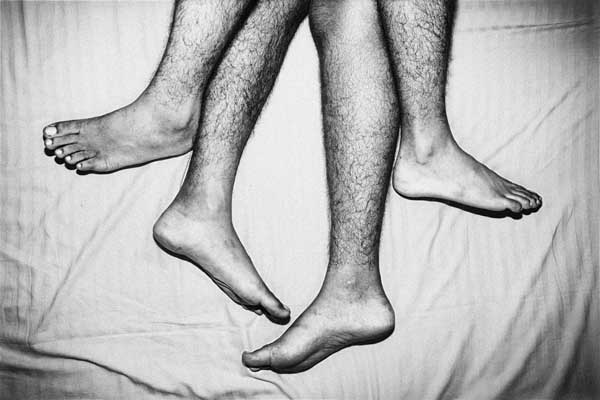

The early work of Abir Abdullah, produced at a time when the genre of photo essays was largely unexplored in Bangladesh, was emulated by others in his own batch like GMB Akash. Akash himself became a trendsetter for future students. The gritty colours of Andrew Biraj and the ethereal black and whites of Munem Wasif took divergent exploratory routes while their classmate Nazrul Islam, found inroads into contemporary life in Kabul. The exquisite image construction of Saiful Huq Omi was perhaps the precursor of the equally accomplished sculptural images of Khaled Hasan. Din Mohaammad Shibly?s exploration of family life might well owe to the tender insight by Munira Morshed Munni into the intimacies of her own home. The stark rendering of the invisible gay community by Gazi Nafiz Ahmed, might have evolved from the very different approach that Akash had taken many years earlier, while Masud Alam Liton stayed closer to the early documentary style. Noor Alam?s insightful look at children with thalassaemia surely gained from the work on children with cancer by Nayemuzzaman Prince.

Choosing from the 8th batch was particularly challenging. While the individual styles of Debashish Shom, Shehab Uddin and Shumon Ahmed have all made it to the book, the ones left out include important work by Chandan Robert Rozario, the strong graphic imagery of K M Asad, the harrowing story by Saikat Majumder and the exquisite well-crafted frames of Khaled Hasan. The distinctive approaches of Tanvir-ul-Hossain and Nurun Nahar Nargish, could have represented the new contemporary movement in Bangladeshi photography. They too got bypassed because more thought provoking work was on offer.

Taslima Akhter brings us face to face with the inequalities of class that fuel our growing economy, but lost were Ashraful Awal Mishuk?s insights into the Bangladeshi underworld. Giving up Syed Asif Mahmud?s dreamy visuals was particularly heart wrenching. The well executed night scenes by Sarker Protick fought its way in, but it was the joy of seeing exciting, vibrant, exploratory work by the young photographers, Arifur Rahman, Rasel Chowdhury, Tushikur Rahman and Jannatul Mawa that got the adrenaline going. They refuse to be hemmed in by the four corners of a frame. They reject the notion of walls. This is Pathshala and Bangladeshi photography shamelessly showing off. Long may it do so.

Skip to content

Musings by Shahidul Alam