Can the execution of Mujib?s assassins finally deliver the country from its darkest chapter?

By SALIL TRIPATHI

Published in “The Caravan”: 1 April 2010

A QUARTER CENTURY AGO I met a man who calmly told me how he had organised the massacre of a family. He wasn?t confessing out of a sense of remorse; he was bragging about it, grinning as he spoke to me.

I was a young reporter on assignment in Dhaka, trying to figure out what had gone wrong with Bangladesh, which had emerged as an independent nation after a bloody war of liberation 15 years earlier, in 1971. The man I was interviewing lived in a well-appointed home. Soldiers protected his house, checking the bags and identification of all visitors. A week earlier he had been a presidential candidate, losing by a huge margin.

He wore a Pathani outfit that looked out of place in a country where civilian politicians wore white kurtas and black vests, and men on the streets went about in lungis. He had a thin moustache. He stared at me eagerly as we spoke, curious about the notes I was taking, trying to read what I was writing in my notepad. He sat straight on a sofa, his chest thrust forward, as if he was still in uniform. He looked like a man playing a high stakes game, assured that he would win, because he knew someone important who held all the cards.

His name was Farooq Rahman, and he had been an army major, and later, lieutenant-colonel. He had returned to Bangladesh recently, after several years in exile in Libya. Before dawn on 15 August 1975, he led the Bengal Lancers, the army?s tank unit under his command, to disarm the Rokkhi Bahini, a paramilitary force loyal to President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his Awami League party. When he left the Dhaka Cantonment, he had instructed other officers and soldiers to go to the upscale residential area of Dhanmondi, where Mujib, as he was popularly known, lived. Soon after 5:00 am, the officers had killed Mujib and most of his family.

I had been rehearsing how to ask Farooq about his role in the assassination. I had no idea how he would respond. After a few desultory questions about the country?s political situation, I tentatively began, ?It has been widely reported in Bangladesh that you were somehow connected with the plot to remove Mujibur Rahman from power in 1975. Would you??

?Of course, we killed him,? he interrupted me. ?He had to go,? he said, before I could complete my hesitant, longwinded question.

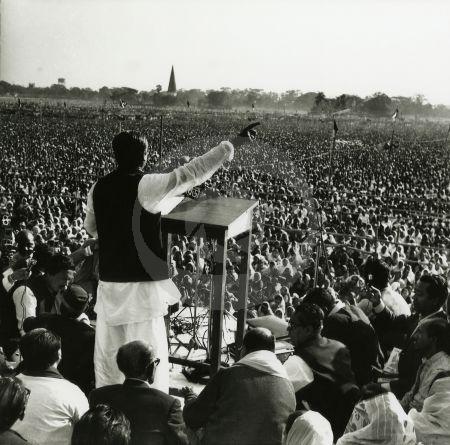

The courtyard outside the jail where Sheikh Mujibur Rahman?s killers were executed.

F AROOQ RAHMAN BELIEVED he had saved the nation. The governments that followed Mujib reinforced that perception, rewarding him and the other assassins with respectability, political space, and plum diplomatic assignments. One of Mujib?s surviving daughters, Sheikh Hasina Wajed, who inherited his political mantle and who was to become the prime minister of Bangladesh, was marginalised for many years. She lived for a while in exile, and for some time, was detained. The political landscape after Mujib?s murder was unstable. Bangladesh has had 11 prime ministers and over a dozen heads of state in its 39-year history. Hasina was determined to redeem her father?s reputation and seek justice, and her quest has larger implications for Bangladesh?s citizenry. Hundreds of thousands?and by some estimates perhaps three million?people were killed during Bangladesh?s war of independence in 1971. Tens of thousands of Bangladeshis now wait for justice?to see those who harmed them and their loved ones brought to account. But the culture of impunity hasn?t disappeared. It took more than three decades for Sheikh Hasina to receive some measure of vindication.

S OMETIME IN THE AFTERNOON of 27 January this year, Mahfuz Anam received a call from an official, saying that the end was imminent. Anam was in the newsroom of Bangladesh?s leading English newspaper, The Daily Star, which he edits. He knew what the message meant: perhaps within hours, five men?Farooq, Lt-Col Sultan Shahriar Rashid Khan, Lt-Col Mohiuddin Ahmed, Maj Bazlul Huda, and army lancer AKM Mohiuddin? would be hanged by the neck until dead at the city?s central jail. Anam told his reporters to be prepared, and sent several reporters and photographers to cover the executions.

?We had hints that the end was near, particularly when the relatives of the five men were asked to come and meet them with hardly any notice,? Anam told me during a long telephone conversation a week after the executions. ?The authorities had told the immediate families that there were no limits on the number of relatives who could come, and they were allowed to remain with them until well after visiting hours. We knew that the final hours had come.?

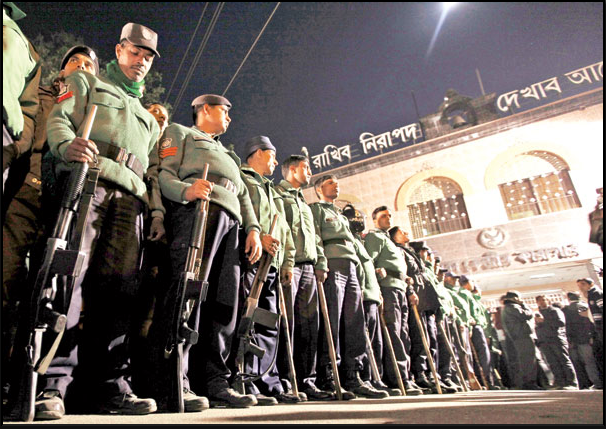

Once the families left, the five men were sent to their cells. They were told to take a bath and to offer their night prayers. Then the guards asked them if they wanted to eat anything special. A cleric came, offering to read from the Qu?ran. Around 10:30 pm, a reporter called Anam to say that the city?s civil surgeon, Mushfiqur Rahman, and district magistrate Zillur Rahman had arrived at the jail. Police vans arrived 50 minutes later, carrying five coffins. The anti-crime unit, known as the Rapid Action Battalion, took positions providing support to the regular police force to prevent demonstrations. Other leading officials came within minutes: the home secretary, the inspector general of prisons, and the police commissioner. Rashida Ahmad, news editor at the online news agency, bdnews24.com, recalls: ?Many media houses practically decamped en masse to the jail to ?experience a historic moment? firsthand.? Anam told me, ?By 11:35 pm, we knew it would happen that night. We held back our first edition. The second edition had the detailed story.?

Bazlul Huda was the first to be taken to the gallows. He was handcuffed, and a black hood covered his face. Eyewitnesses have said Huda struggled to free himself and screamed loudly, as guards led him to the brightly lit room. An official waved and dropped a red handkerchief on the ground, the signal for the executioner to proceed. It was just after midnight when Huda died. Muhiuddin Ahmed was next, followed by Farooq, Shahriar, and AKM Muhiuddin. It was all over soon after 1:00 am.

Earlier that day, the Supreme Court had rejected the final appeal of four of the five convicts. Shahriar was the only one not to seek presidential pardon. His daughter Shehnaz, who spent two hours with her father that evening, later told bdnews24.com, ?My father was a freedom fighter; and a man who fights for the independence of his country never begs for his life.?

Mujib?s daughter, Sheikh Hasina, was at her prime ministerial home that night. She was informed when the executions began, and she reportedly asked to be left alone, and later offered namaz-e-shukran (a prayer of gratitude). Many people, most of them supporters of the Awami League, had gathered outside her house that night, but she did not come out to meet anybody. A few days later, she told a party convention that it was a moment of joy for all of them, because due process had been served.

Former Lt-Col Syed Farooq Rahman, convicted in the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, being led to court in a prison vehicle.The mood was sober and subdued. Dhaka residents I spoke to told me the celebrations were only in certain localities. Ahmad, who was at her news desk until late at bdnews24. com, wrote to me, saying the mood was sombre, and many looked at it as a time for reflection, although that night and the following day there was muted rejoicing in some areas. Many could understand Hasina thanking God, and other politicians welcoming the closing of a dark chapter, but some felt it a bit much that parliament itself thanked God and adjourned for the day, she said.

The chapter is not yet closed. In early February, Awami League activists ransacked and set afire the home of the brother of Aziz Pasha, one of the self-confessed conspirators who had died in exile in Zimbabwe a few years ago. Six other conspirators remain at large, and the Government says it is determined to bring them back.

C ALL IT JUSTICE, REVENGE, or closure. It has taken 34 years for this particular saga to reach its end. Khondaker Mushtaq Ahmed, who took over as Bangladesh?s president after Mujib?s assassination, had granted the officers immunity and praised the assassins. General Ziaur Rehman, who later became president, con- firmed the immunity. A series of articles in August 2005 were published simultaneously in The Daily Star and Prothom Alo, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the coup d??tat that killed Mujib and much of his family. Lawrence Lifschultz, an American journalist who had been South Asia Correspondent of the Far Eastern Economic Review in the 1970s, revealed that one of his principal sources, alleging CIA links with the political leadership of the coup, was the US Ambassador to Bangladesh, Eugene Boster.

While Boster sought anonymity during his lifetime, Lifschultz disclosed after Boster?s death that the ambassador had in 1977 informed he and his colleague, the American writer, Kai Bird, that the US Embassy had contacts with the Khondaker group six months before the coup, and that the ambassador had himself ordered that all links with Khondaker and his entourage be severed. Boster claimed he learned later that behind his back the contacts continued with Khondaker?s associates until the actual day of the coup.

In their book, Bangladesh: The Unfinished Revolution (1979), Lifschultz and Bird document Khondaker?s prior links to a failed Kissinger initiative during the 1971 war. Khondaker?s colleagues in Bangladesh?s government-in-exile had discovered his covert contacts with Kissinger, and it ended with him being placed under house arrest in Calcutta. Four years later, Khondaker?who was in Mujib?s cabinet?became president after the military coup, and once in office, he granted immunity to the assassins.

Later governments gave some of the assassins high-ranking posts, even though these men had conspired to eliminate the country?s elected leader. Lt- Col Shariful Haq Dalim represented Bangladesh in Beijing, Hong Kong, Tripoli, and became high commissioner to Kenya, even though he had attempted another coup in 1980. Lt-Col Aziz Pasha served in Rome, Nairobi, and Harare, where he sought asylum when Hasina first came to power in 1996. She removed him; he stayed on in Harare, and died there. Maj Huda was briefly a member of parliament, and also served in Islamabad and Jeddah. Other conspirators served Bangladeshi missions in Bangkok, Lagos, Dakar, Ankara, Jakarta, Tokyo, Muscat, Cairo, Kuala Lumpur, Ottawa, and Manila.

The Oxford-trained lawyer, Kamal Hossain, who was Mujib?s law minister, and later foreign minister, told me, ?The impunity with which Farooq operated was extraordinary. When he returned to Bangladesh, the government facilitated him and President [Hussain Muhammad] Ershad, who wanted some candidate to stand against him in the rigged elections. [Ershad] let Farooq stand to give himself credibility.?

The flag of Bangladesh raised at Mujibur?s residence on 23 March 1971, three days before the official independence from Pakistan.It was clear that a trial of the assassins would only be possible if Mujib?s party, the Awami League, came to power. That happened in 1996, and Mujib?s daughter, Sheikh Hasina, became prime minister. The cases began and the court found all 12 defendants guilty. But Hasina lost the 2001 elections, and the process stopped, resuming only after her victory in the elections of December 2008. The government now wants to bring the surviving officers back to Bangladesh: Noor Chowdhury is reportedly in the United States; Dalim is in Canada; Khandaker Abdul Rashid, Farooq?s brother-in-law, is in Pakistan; MA Rashed Chowdhury is in South Africa; Mosleuddin is in Thailand; and Abdul Mazed is in Kenya. Bringing all of them back may not be easy, because they will face executions. Canada and South Africa have abolished the death penalty, and Kenya put a stop to it recently, making it harder for those governments to extradite them.

How does a nation, whose independence was soaked with blood, which lost a popular leader of its freedom struggle in a brutal massacre, reconcile with that crime? What form of justice is fair? Does the death penalty heal those wounds?

Bangladesh thinks so. It is among the 58 countries (including India) that retain the death penalty, but it applies it only in rare cases, like murder. In 2008, five people were executed in Bangladesh. Many governments oppose the death penalty on principle, and the European Union appealed to the Bangladeshi government to commute the sentence of Mujib?s assassins. The human rights group Amnesty International also sought clemency, while agreeing that the men should face justice.

Bangladeshi human rights lawyers have found it hard to challenge the death penalty because it is not controversial in Bangladesh. There are also political exigencies. One human rights activist told me, ?We are against [the] death penalty but the dilemma is that we are in a country where life imprisonment really means imprisonment guaranteed until your party is in power. The death penalty is almost seen as the only way to guarantee justice for such a grisly crime.? Grisly, it certainly was. This is what happened.

Next Page

2 thoughts on “Bangladesh's Quest for Closure”